Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 21 Aug 2024

posted on 21 Aug 2024

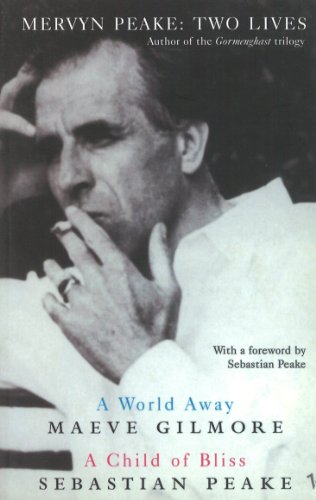

A World Away by Maeve Gilmore & A Child of Bliss by Sebastian Peake

In the very late-60s and early-70s I was besotted with Mervyn Peake’s extraordinary Gormenghast trilogy, Titus Groan, Gormenghast and Titus Alone. I was desperate for anything I could find out about the man who had written them and a few years later, after I had started working as a bookseller, I remember the excitement of coming across A World Away, a memoir of Peake written by Maeve Gilmore, his wife. This was first published in 1971 but for some years now has been available in a single volume combined with A Child of Bliss, a memoir by Sebastian Peake, the couple’s oldest son.

An earlier Letterpress piece does a good job of explaining how and why Peake seemed so vital a presence to the counterculture audience of the late-60s which rediscovered the man’s work, but I still need to try and describe the world of Gormenghast. It is a remote, decaying earldom apparently unchanged in centuries – a sort of castle-kingdom locked in the changeless, futile aristocratic rituals of its ruling Groan family, of which Lord Sepulchrave is the 76th Earl and whose successor, the 77th Earl, Titus, is born as the first volume opens.

Beyond the walls of Gormenghast an impoverished peasantry live in little more than mud-walled huts. From amongst them ‘Bright Carvers’ are chosen who spend their lives creating wooden carvings that glorify the Groan name and the rituals that perpetuate it. But there is something rotten at the heart of Gormenghast; revolution and tragedy are brewing and in the squalid kitchens, where grease and condensation pour down the walls and the brutal and gargantuan head chef, Swelter, exercises ruthless control over his scullions, a young boy is growing up whose burning ambition is to see Gormenghast toppled.

The astonishing thing about Peake’s trilogy, I think, whether considered at the time the first volume appeared in 1946, or in 1969 when the Penguin Modern Classics edition brought his extraordinary vision to a new audience, is that it seemed to have no precedent. Who was Mervyn Peake? Where did these books come from? What inspired them? And what did they mean – for it seemed inconceivable that such an unrelentingly detailed vision of social ossification and decay could be without deeper meaning.

Those of us discovering the books in the late-60s thought we had found an heir to Tolkien, as grand and as fantastical, but a better-kept secret. We were wrong, of course. Anthony Burgess, who was a great champion of the Gormenghast books and wrote a preface to the Penguin edition said with far greater accuracy: ‘it remains essentially a work of the closed imagination, in which a world parallel to our own is presented in almost paranoic denseness of detail.’ Not a magical fantasy kingdom, but ‘a world parallel to our own’: that exactly captures the tone of the books.

Gilmore’s memoir is fairly lightly sketched in but in its quietly informal and intimate way it does a marvellous job of filling in Peake’s early childhood in China where his parents were serving as medical missionaries when he was born, the trauma of his war years – his request to become an official war artist was rejected and he was enlisted in a sapper regiment – and the artistic and cultural bohemia the couple moved in from the early-30s onwards. But central to Gilmore’s account, of course, is the tragedy of the illness – Parkinson’s disease and associated mental and physical health problems – that began around 1955 and resulted in Peake’s death aged just fifty-seven in 1968.

As I say, when I first read the Gormenghast trilogy I thought it was marvellous, but all my efforts to reread it in recent years have been unsuccessful. It offers such a densely imagined world that to read it is at times to feel almost stifled. But Gilmore’s memoir helps us understand to some degree the compulsion under which Peake wrote these books. For instance, in her view the first book was a repository for his early memories of China, Gormenghast’s ‘mud people’ a parallel to the impoverished Chinese peasantry living up against the walls of the American compound where the family lived. But the writing of this first volume was also one of the ways that Peake coped with the loneliness and alienation of war-time army life. In the second volume the tragic tone deepens, reflecting some of Peake’s post-war trauma. And the third volume, written only with the most immense effort as Peake’s physical and mental health was collapsing is heavily influenced by what he saw while documenting the liberation of the Belsen extermination camp, which he visited with the journalist Tom Pocock.

Rereading A World Away makes me realise afresh that Peake’s trilogy needs to be understood in the context of war and post-war trauma rather than as some kind of continuation of the tradition of ‘gothic’ fantasy novels – a term, incidentally, that the couple considered lazy and inaccurate. It certainly makes me want to try the Gormenghast books again, this time in a more informed and sympathetic frame of mind. In a more general sense, Gilmore’s memoir restores Peake to his rightful place in the artistic firmament of the first half of the twentieth century and it is a book that deserves to stand alongside those of her husband.

I’m afraid I don’t feel that the same can be said of Sebastian Peake’s memoir. It has its moments of interest but he wasn’t a natural writer and it has a rather scrappy and under-edited air about it. Real Peake fans, however, will almost certainly find value in being able to compare the perspectives of mother and son. What most surprised me about the book was how unhappy Sebastian Peake seems to have been, both as a child and as a man, because I don’t remember this coming across in Maeve Gilmore’s account. Sebastian died quite suddenly in 2012 aged seventy-two.

Alun Severn

August 2024

Elsewhere on Letterpress:

Boy In Darkness by Mervyn Peake