Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 21 Feb 2024

posted on 21 Feb 2024

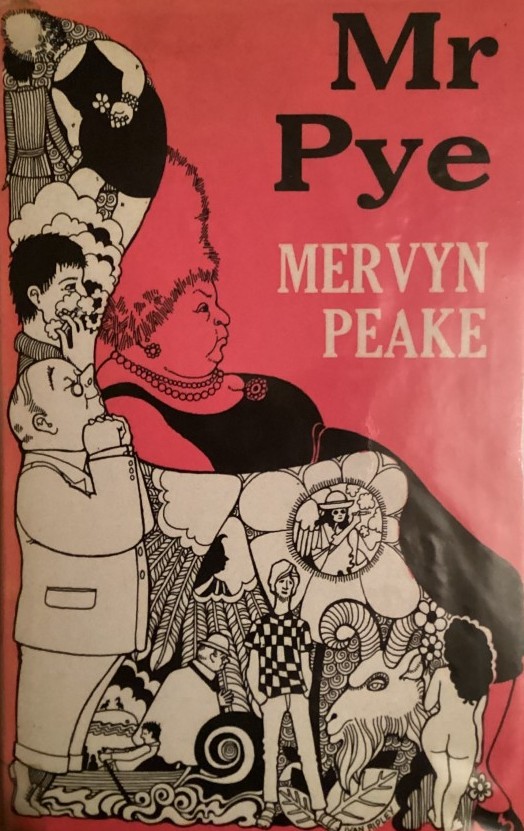

Mr Pye by Mervyn Peake

I’m not at all sure why but over time I’ve found myself drawn to quirky, off-centre novels from the early to mid-20th century that have unconventional perspectives on religion. My interest was originally piqued by Arthur Calder-Marshall's The Fair To Middling, then T.F. Powy’s Unclay which I found myself enjoying hugely despite going to it sceptically and imagining that I’d probably hate it. I followed that up a little later with Powys’ best-known novel, Mr Weston’s Good Wine and, just a few months ago, Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes – and now along comes Mervyn Peake’s Mr Pye.

Mr Pye, published in 1953, came along at about the mid-point of the more famous Gormenghast trilogy (Titus Groan and Gormenghast had been published but Titus Alone was still to come) but the tone of the book and the nature of the story are completely different. I imagine that it has been described by some readers as a humorous or comic novel but a label like that would do it no favours at all – it’s much odder than that.

We first meet the endearingly rotund Mr Pye (who, by the way he is described, would be a ringer for the actor, Arthur Lowe) as he heads towards the Channel Island of Sark with a mission in mind. We don’t have any idea of Mr Pye’s back-story up to this point but we do know now he’s enthused by the mission of bringing the message of his ‘Great Pal’ – God to you and me – to the recalcitrant population of the small island.

His starting point is his new landlady, the acidic and angular, Miss Dredger. Her world is dominated by an unforgiving feud with her neighbour, Miss George but through the sheer force of his personality he contrives a reproachment between the two. Gradually his unstinting good humour and the messages of his ‘Great Pal’ begins to influence the whole island. It seems that only the nubile Tintagieu, a young woman dedicated to her animal passions, is able to keep Mr Pye at arms-length.

But then, unaccountably, things take an odd turn – Mr Pye begins to grow wings on his back. What are these? Is he, as he assumes, turning into an angel? Is this a reward for his good deeds?

He heads off back to the mainland to see if a doctor has any answers for him - but all to no avail. In desperation he decides that maybe he can find the answer for himself – if he now starts being bad rather than good, maybe the wings will disappear. His assumption is right – but there’s another catch: as the wings shrink he starts to grow horns.

As might be expected, his sudden change of attitude and the emergence of the horns doesn’t exactly make his popular with the local population and there’s a pretty extraordinary climax to the story that I won’t reveal here because you’ll want to read that for yourselves.

Good luck unravelling the theology that lies behind this allegory because I’m not at all sure I really understand what we take away from this. Peake isn’t, of course, a negligible writer and his powers of fantasy are formidable – so there are plenty of moments, portraits and episodes that will delight but when they are taken all together they seem to add up to less than their parts.

It’s undoubtedly a cult book and there are plenty of readers who will love this more than I did. So, if you’re new to Peake or if you want something quirky and challenging in a low key way, you might want to read it and make your own mind up about what the key messages are.

Paperback copies are easily found but the hardback is quite elusive. The one I read and shown here is a 1969 reprint but the 1953 first edition is punishingly expensive.

Terry Potter

February 2024