Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Oct 2016

posted on 05 Oct 2016

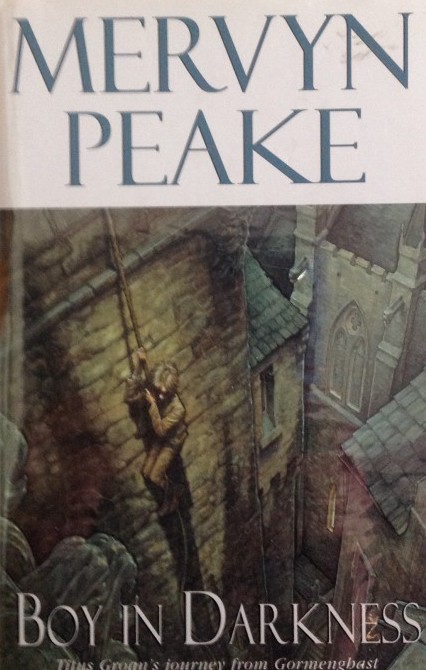

Boy In Darkness by Mervyn Peake

Back in the late Sixties when I was still a teenager, I desperately wanted to be associated with the ideas and lifestyle of the counter-cultural underground of the day. In retrospect I realise now just how little I understood about the sort of ideas that were coming out of the USA and France but I was excited by the notion that there was ‘something in the air’ and that there was more to life than the dull, grey conformity of working class Birmingham. The music you listened to and the books you read were crucial badges of identity for me and other young people like me who had no real prospect of being on the barricades or the intellectual frontline and being seen to subscribe to ideas that were scorned by the ‘establishment’ was vital. In amongst the books you had to have at that time was Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy – an odd Gothic fantasy started in 1946 and completed in 1959. Peake actually died in 1968 at the age of 57 in slightly mysterious circumstances but from what turned out to be a rare form of dementia.

So, without really being aware of it, I was probably trying to read Peake’s most famous novels at about the time he actually died. Not that it would have helped much to have known that. I did, I think, read them but I must have done with so little attention or so superficially that I can now recall almost nothing about them – although to be fair I do still have a sense of the peculiar atmosphere that pervades the books. When, not long ago, I came upon a copy of a short novella by Peake called Boy In Darkness it was cheap enough for me to buy out of curiosity and out of a (probably misplaced) notion that I might revisit his writing sometime soon. Going through a pile of unread stuff on one of my shelves the other day Boy In Darkness popped up again and given it’s only a slim volume I decided to fill a couple of hours with it.

First published in 1956 as part of a collection called Sometime Never: Three Tales of the Imagination this story is, the short preface tells us, ‘based on Titus Groan from the Gormenghast trilogy’ but stands as a short story of Gothic horror in its own right. The story tells us of Boy (Titus) and his escape from tedious hours of boredom he spends in the wastes of the castle of his kingdom. Seeking another world he sets out into the featureless lands of dust and pursued by demon-eyed dogs he crosses water into another land of even greater peril. He is taken captive by a mutant creature known only as Goat who is in turn in thrall to the even more terrifying Hyena. Both want to take Boy as a captive offering to their master, the sinister Blind Lamb. Lamb it turns out is the root of all evil – a sort of inverted demon Christ-figure – who, for amusement turns all living things in the kingdom into mutant half-man half-animal creatures. None but Goat and Hyena have ever survived the awesome power of Blind Lamb and are now the only living things in the realm – so the appearance of boy excites Lamb into a frenzy of expectation, planning how he will convert him into a living monstrosity.

I won’t reveal here how it happens but Boy escapes the terrible subterranean halls that Lamb inhabits and is returned to the castle he had originally escaped from.

This really must be one of the most bizarre, disturbing and hallucinogenic stories I’ve read for some time. Part fantasy novel, part Poe horror story and part neo-religious (or even blasphemous) fable it takes some time to tune into the style and vocabulary of Peake’s creation. Once you’re there ( and I suspect some people will never find this something they can reconcile themselves to) it’s a pretty extraordinary experience and one which has genuine undertones of real terror about it. There’s a strong emphasis on the visceral and sensual – the senses of smell and touch are exaggerated and emotions like disgust, revulsion and a fearful anticipation of unknowable horror constantly crop up, abate and then re-emerge.

The book is only a little over 100 pages long – which includes the atmospheric drawings of the illustrator, P.J. Lynch, who I normally associate with a number of somewhat less traumatic children’s classics but whose style seems perfectly suited to this enterprise. The copy I found and which is shown in the illustration above was published in 1996 by Hodder and you’d expect to pay under £10 for a hardback copy and less for paperback.

Terry Potter

October 2016