Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 17 Jul 2023

posted on 17 Jul 2023

Elidor by Alan Garner

Continuing Letterpress’s exploration of children’s fiction from the 1960s and 70s (see this post for many of the relevant links), I have just reread Alan Garner’s third novel, Elidor (1965). It turned out to be very different to how I remembered it. Despite its brevity and being a little underdeveloped in parts, it is a sophisticated novel with real emotional heft. It is also one of Garner’s most atmospheric and evocative novels.

Elidor is also notable in Garner’s output for a few other reasons. It is his only novel to have an urban setting. It seems to reject some of the conventions of children’s fantasy literature of the time, such as the Narnia books by C. S. Lewis and in fact Garner has referred to it as being ‘subconsciously’ an ‘anti-Narnia novel’. And it is a very dark and troubled novel, its central themes dislocation and destruction – especially when a consequence of rapid social and economic change.

The novel takes place in Manchester and its suburbs in the early-1960s, at a time of great change in the urban landscape, and this is reflected in the events of the novel. It is late November; the first Christmas shoppers are out in force. Four siblings – Nicholas, David, Roland and Helen – are about to move house: the family is relocating to one of Manchester’s leafier suburbs. The children are already anxious about this – it is a move which will mean they are further from their friends and their schools and the familiar places and neighbours amongst which they have grown up.

One afternoon, cold and bored, the children are hanging about in central Manchester trying to think of something to do. Roland is looking at the visitors’ street map of the city – turning its handles to shift the map across its grid references – and his attention is drawn by a curious little street they have never previously spotted: Thursday Street. They set out to find it. It turns out to be in the heart of a slum clearance area – a sinister and dangerous warren of partly demolished Victorian buildings, collapsing back-to-back houses and bomb-sites left over from the Blitz.

A partly demolished Victorian church proves to be a portal to the magical kingdom of Elidor. But Elidor too is a wasteland: war, dark magic, famine and invasion have reduced it to an ashen landscape of ruins and decay. But Malebron, a man whom they meet there – an injured king? a maimed wanderer? an itinerant musician deranged by war and suffering? – tells the children that they have a place in the myths of Elidor and are destined to play a role in the quest for four objects which together can save Elidor and restore it to the light.

If I’m perfectly honest, I don’t think the ‘mechanics’ of Garner’s story are quite satisfactorily worked out in this novel. The traditional ‘quest’ narrative seems to be a little shoehorned-in and the precise purpose of these magical objects – a sword, a spear, a stone and a goblet – isn’t always clear. Rather than magic itself, it seems that in this novel Garner is more concerned with the effect that magic has on ordinary people – for instance, whether they are able to rise to its challenges and understand what is happening. Perhaps this is what he meant when he said it was an ‘anti-Narnia’ novel. It doesn’t always quite work but it is a fascinating experiment.

I must say that virtually none of the things I have mentioned in this review were evident to me when I first read the book back in the early-1970s but surely this is a measure of Garner’s accomplishment: that a children’s novel written over sixty years ago still has strange, hidden depths waiting to be revealed.

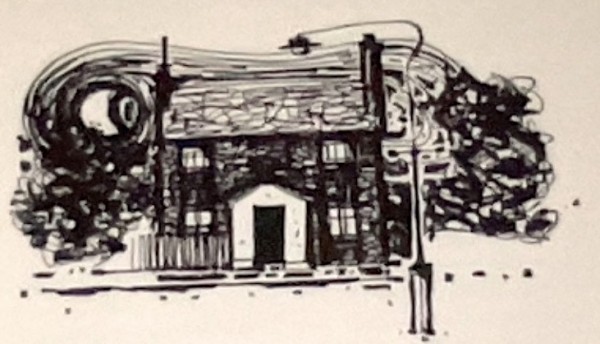

This particular edition benefits hugely from Charles Keeping’s wonderful illustrations. It is one of those books which I find has become extraordinarily potent: just to see its marvellous cover and Keeping’s dense, swirling line drawings – they seem scarcely able to contain their jostling energy – is to be transported back to those years when I was just discovering Alan Garner’s work for the first time.

Alun Severn

July 2023

Alan Garner elsewhere on Letterpress: