Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 24 Apr 2022

posted on 24 Apr 2022

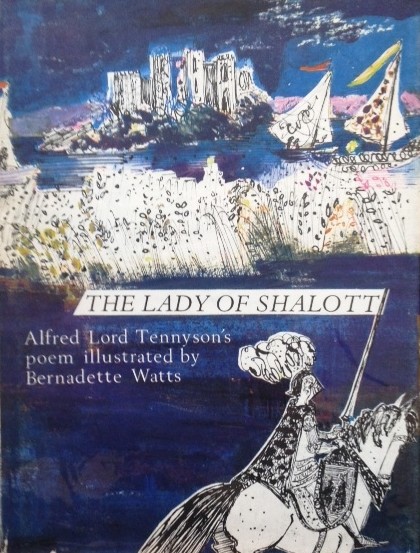

The Lady of Shalott by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, illustrated by Bernadette Watts

Tennyson’s fascination with the Arthurian legends picked up on a wider cultural fixation with a sort of cod-medievalism that captured the imagination of artists and writers at the back end of the 19th century – especially the likes of Edward Burne-Jones and what had become known as the Pre-Raphaelite painters. Indeed, Tennyson’s literary status was such that he not only echoed this wider fascination with all things Arthurian but actually became one of the key influencers of that movement. His interpretation of a 13th century Italian romance Donna di Scalotta which he called The Lady of Shalott, became one of his most famous and influential poems.

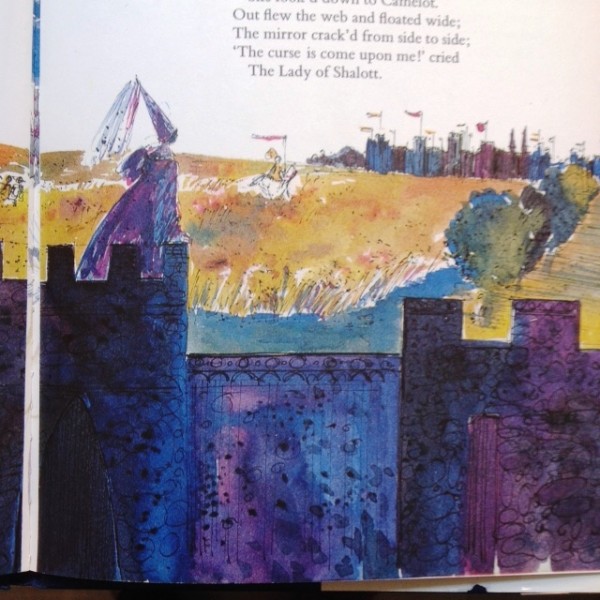

The poem is (or certainly was) a standard for inclusion in secondary school poetry anthologies and I remember English lessons where we were set the task of memorising large chunks of it in order to be able to sit and recite it as if we were a weird religious community chanting some kind of mysterious prayer or incantation. I can still do that to order with chunks of the poem but I have no residual memory of ever talking in that classroom about what on Earth the poem was all about. Specifically, just why brave Sir Lancelot was moved to sing ‘tirra-lirra, tirra-lirra' as he rode boldly to Camelot – a line that always corpsed the poor soul deputed to chant out that particular line.

All these years on, I can say that I’m not that much more well-disposed to the poem than I was back in that classroom. True, I understand some of the ambiguities within the various interpretations that have been placed on the poem: is it, for example, about the position of Victorian women and their sexuality in a repressed society? Or maybe about the position of the artist who finds the real world shatters the world of the imagination? Whatever spin is placed on it however leaves me with one undeniable fact - I still don’t much like it.

Perhaps the deadly experience of rote learning simply crushed any chance I ever had of responding positively to this poem – which would, of course, be an indictment of the education system which, I suspect, was fully merited. But it might just be that I don’t like it – plain and simple.

What I do very much like however is the illustrative work of Bernadette Watts and this edition from 1966 when she was just 24 years old does its very best to give readers of all ages a chance to revisit the poem. Watts has gone on to have a stellar career, littered with awards and a remarkable partnership with the children’s publisher, North and South which pioneered the publication of children’s story from a range of international sources.

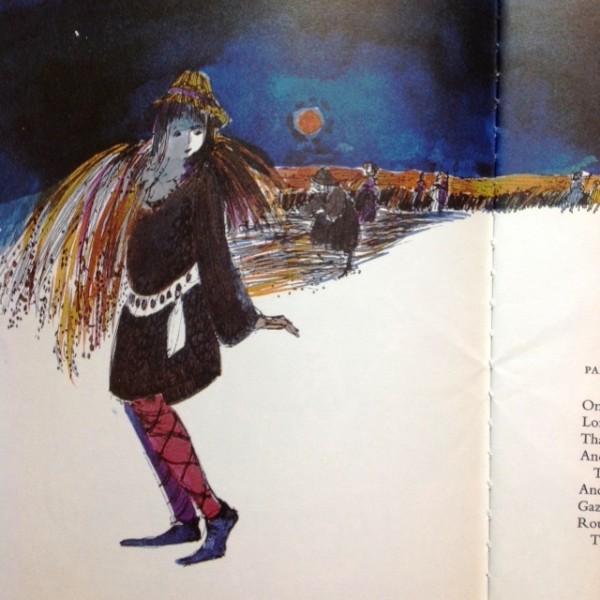

Here, however, the influences of other rising stars of illustration – especially I would suggest David Gentleman and Paul Hogarth – are clear to see. In fact Watts was tutored by Brian Wildsmith and David Hockney – and those influences are clearly also part of the mix.

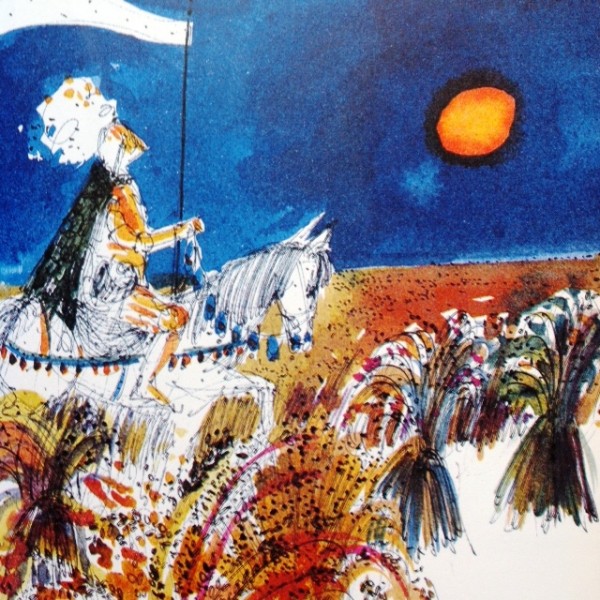

The sumptuous pen and ink wash technique is ideal in helping create the colours to flesh out this imaginary Arthurian landscape. The use of deep cobalt blues grading into purple and laid down in slabs of colour are very much from the Wildsmith workbook and they lend the whole set of illustrations an undeniably 60s feel that I very much appreciate.

This isn’t an easy book to find now, especially in good condition with a dust jacket and Watts’ own website makes no mention of the book – which seems to be out of print at the moment. I came across it on one of my endless trawls around the charity and second hand bookshops and that might ultimely be your best chance of pinning one down.

Terry Potter

April 2022