Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 29 Nov 2018

posted on 29 Nov 2018

Cinderella as part of a topic about Egypt

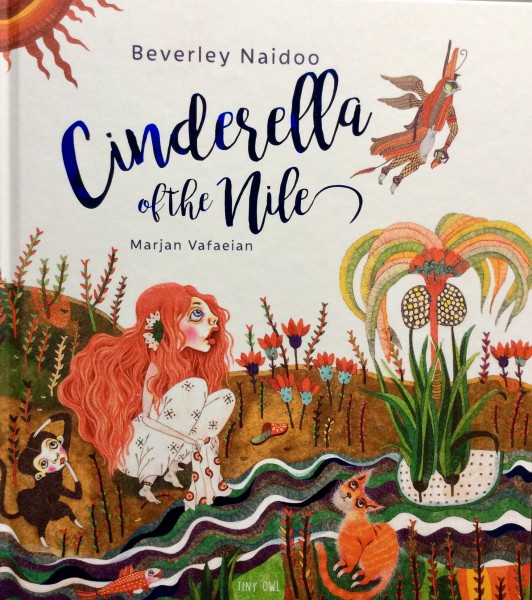

When I was working with a group of Year Three children at Somers Park Primary School in Malvern the other day, we paused to watch a long line of their classmates walking past us with kohl-defined eyes and wearing tea towels on their heads. ‘We’re doing about Egypt’ explained Madison and several of the others then told me some interesting facts about the pyramids and Tutankhamen. As I was planning to work with more of the class on the following day, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to make a link to their topic by introducing them to ‘Cinderella of the Nile’ by Beverley Naidoo, illustrated by Marjan Vafaeian.

I have talked about the book with Beverley and she had been keen to know how children of different ages would respond to her extraordinary story, as she was hoping it would have wide appeal. I had a few reservations about whether it might be a bit too sophisticated for seven year olds, but the results with the two groups that I worked with were very interesting.

I had foolishly made the assumption that they would all be familiar with the more traditional Cinderella story and soon realised that this wasn’t the case. The first group of five boys and one girl were pretty vague about the traditional plot, although a couple had seen the Disney film and another had seen a pantomime version. One boy rolled his eyes saying ‘It’s a girl’s story’ and his friends nodded their heads in agreement. We had a bit of discussion about this, but I think that gender specific stories would be fascinating to talk about further if I ever get the opportunity as all children are of course influenced by marketing and so much more from a very early age. I gave them a few Cinderella story highlights (for example, the glass slipper, the Ugly Sisters and the Prince) to give them a loose framework to measure against this more unconventional version about a girl called Rhodopis (which means rosy –cheeked in Greek) who is kidnapped from her home in Greece and taken as a slave to Egypt. It is based on a story originally told by the Greek historian Strabo, and before him, Herodotus and includes the friendship between Rhodopis and Aesop (they did recognise his name from books they had read before). I then tried reading the whole story aloud, pointing out the illustrations as we went along, but realised that it was too long as some of them lost interest about half way through.

I used a different approach with the next group by skimming through the first half of the book and focussing on the parts that had a more obvious connection to the original Cinderella story towards the end. Had I more time, I definitely would have spent longer on all this and am convinced that it would be an excellent core text for a topic over several weeks. Just imagine how it could be the starting point for creative writing, making detailed maps and the scope for multi- media art work inspired by the story and pictures….

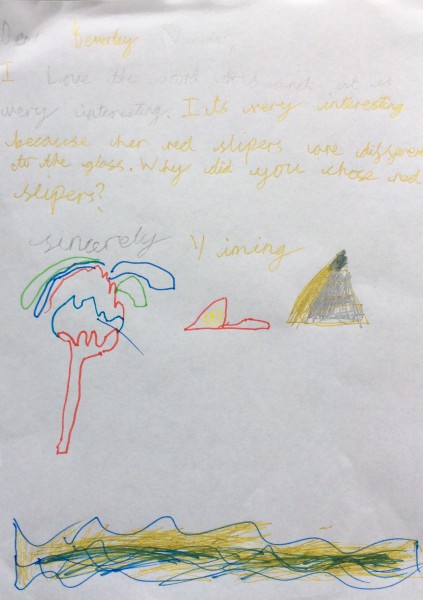

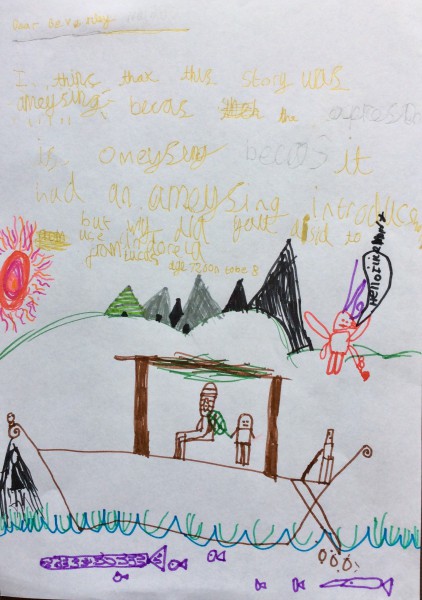

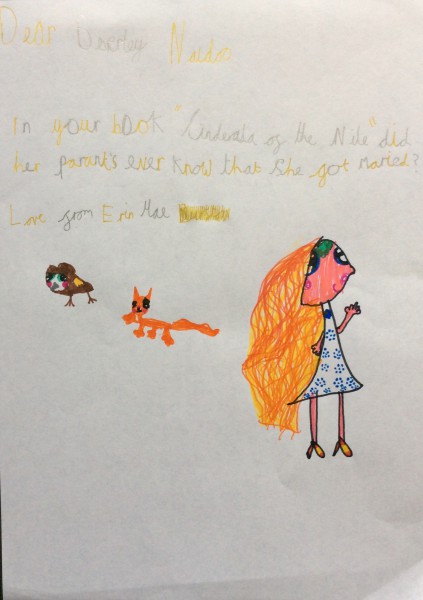

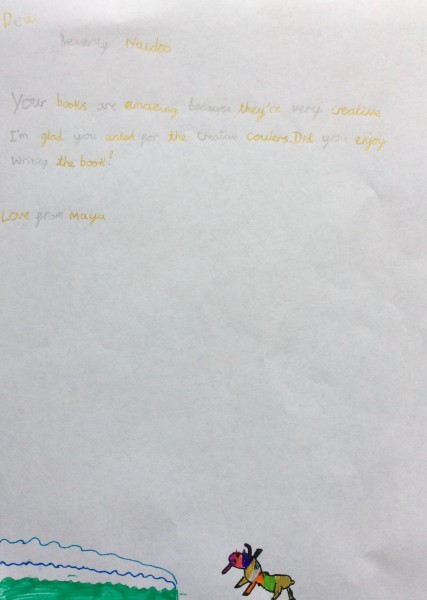

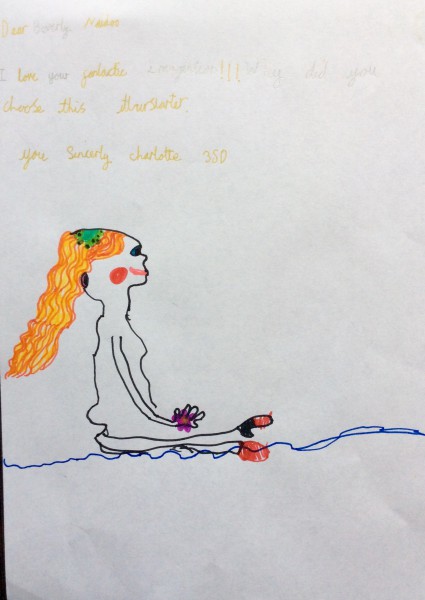

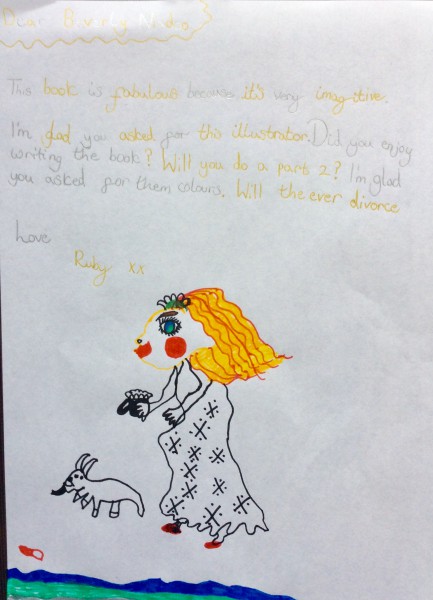

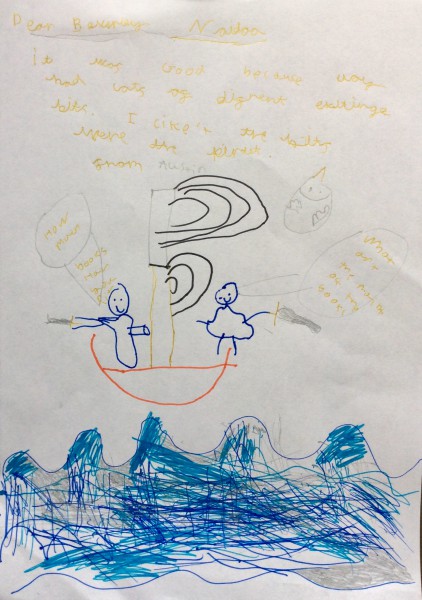

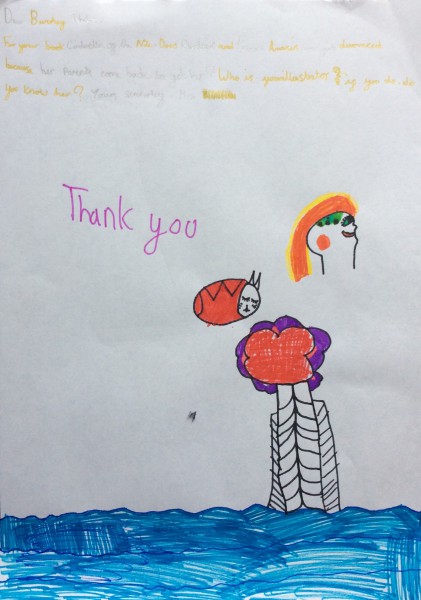

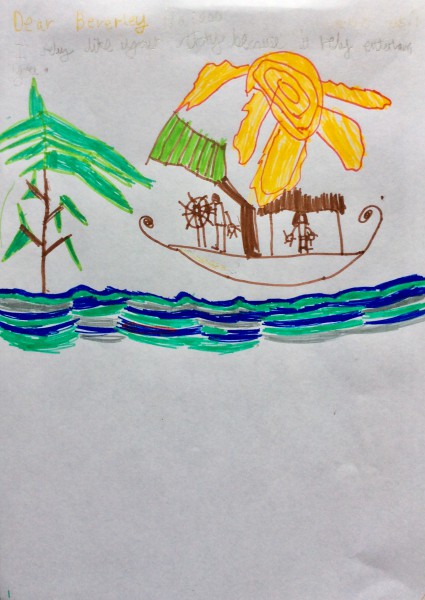

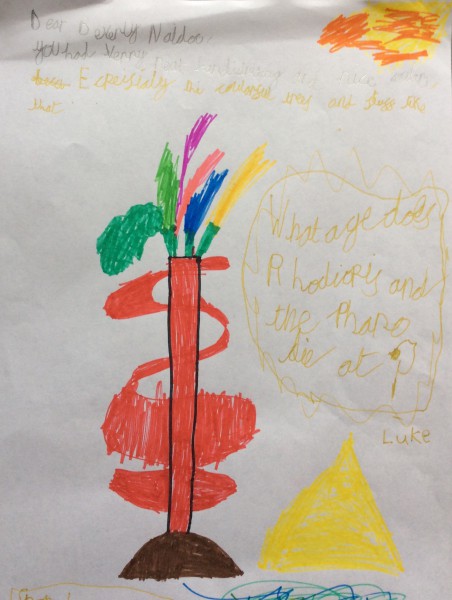

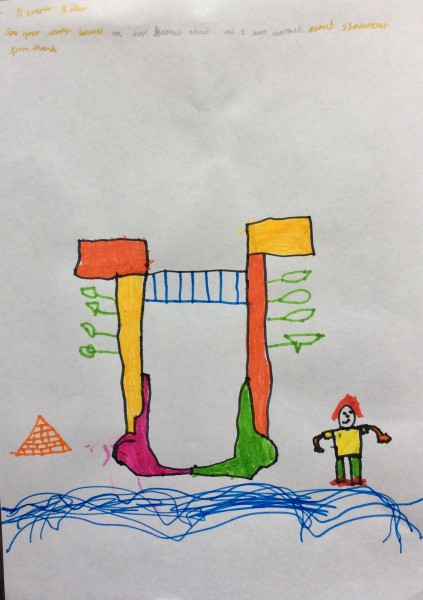

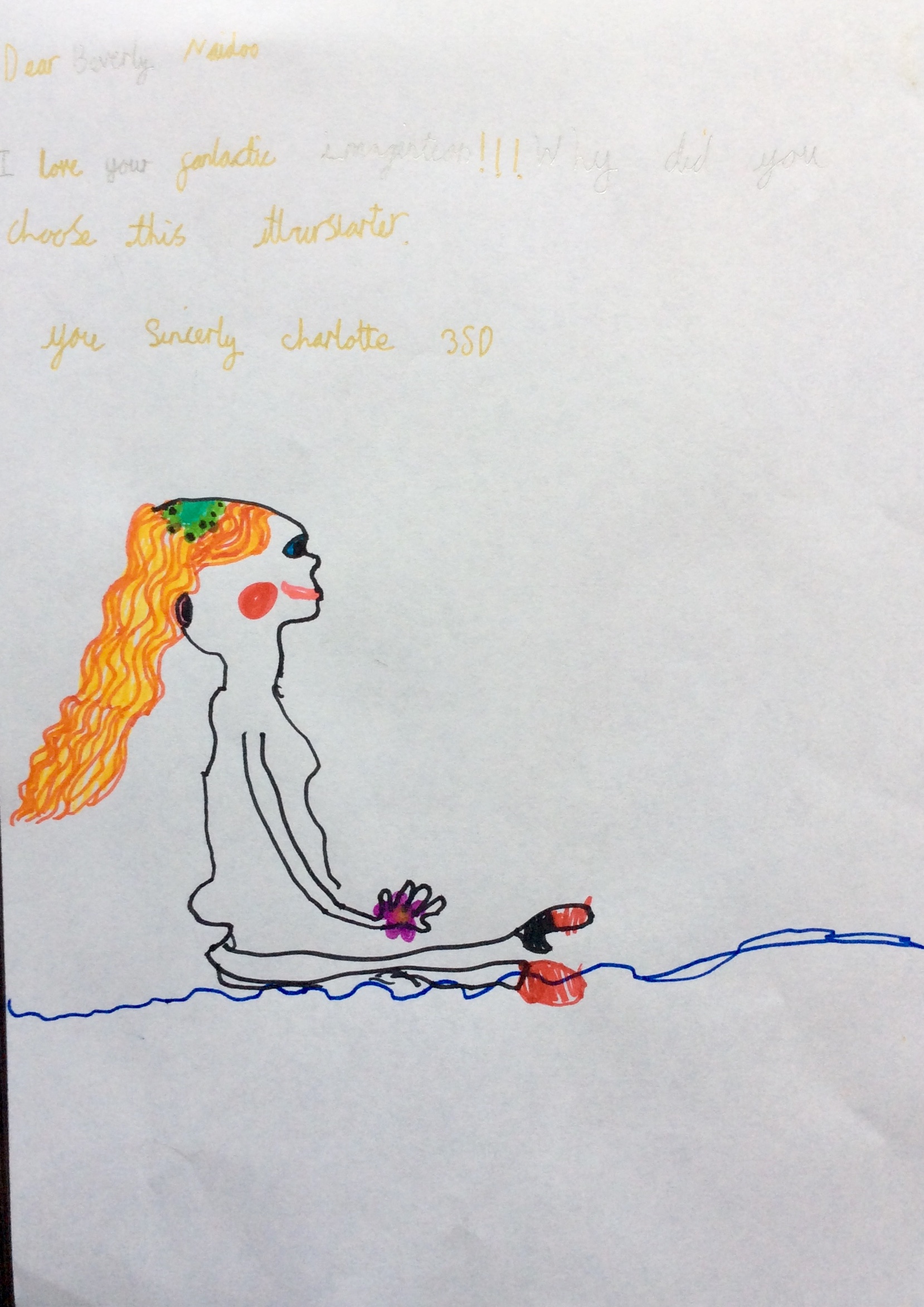

Anyway – I didn’t have that luxury this time, but wanted to get their overall responses written down in illustrated letters to send to Beverley. The results are splendid as you can see below because these children really love the chance to express themselves through writing and drawing. While they were composing their letters we had more discussion about the story. The following exchange (I have changed the names) was an example:

Bryony ‘Pharoahs should be golden’

Craig ‘No that’s just the death mask – they have ordinary skin when they are alive’

Phoebe ‘But I’ve never seen black skin for a Pharoah’

James ‘People in Barbados are black because I saw them on holiday – it’s because it’s hot there’

Poppy ‘You mustn’t talk about black because it’s racist’

This conversation was prompted because the Pharoah Amasis ( the Prince)was depicted as a black man, which is very unusual. I did my best to unpick the misinterpretation of ‘racism’ (not easy in a few minutes) and explained that Egypt was part of North Africa where most people had very dark skin and so he probably did look like that. Perhaps this important subject needs some further attention with their teachers, along with some further reflection about why all the Egyptians in their other books are depicted as relatively pale.

I think that Beverley will definitely appreciate their impressive letters, many of which show Rhodopis with extraordinarily bright red cheeks, and be very keen to respond to their questions which included:

‘How did they understand each other because they speak different languages?’

‘What age did Rhodopis and the Pharoah die at?’

‘Will you do a part 2?’

‘Will they ever divorce?’

I would be very interested to use this rich book again with other groups of children who I am sure would have a range of equally fascinating reactions.

Karen Argent

November 2018