Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 05 Aug 2018

posted on 05 Aug 2018

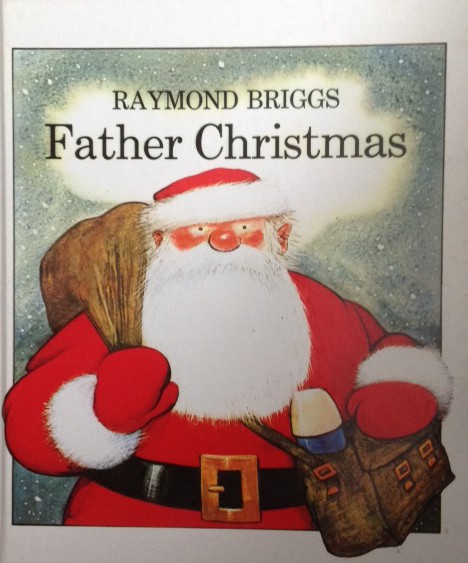

Raymond Briggs

Several years ago we were delighted to see Raymond Briggs make a rare appearance to talk about his books in Cheltenham. Unlike many authors and illustrators of children’s books, he clearly didn’t much enjoy the experience of performing to a live audience, something he has mentioned in several subsequent interviews. When we came out of the talk we reflected that there was no reason why someone who communicates so well through his art should be able to or be expected to be an entertaining performer. I rather admire him for his reticence and also his admission that he doesn’t particularly like the company of children. As a result he is generally regarded as a bit of a grumpy old man akin to one of his best loved characters, Father Christmas, and I am pretty sure that he is ok with that. He is definitely not interested in potential celebrity and often turns down invitations to appear on radio or television. He has had many personal tragedies during his life and suffered with depression. This has evidently coloured his view of the world and the way in which he often focuses on death and other difficult situations faced by ordinary people. The day before his eighty third birthday in 2017, he gave a very revealing interview to India Sturgis where she explained:

‘Part of Briggs’ storytelling genius lies in his bare-faced realism. Endings are never sugar-coated, characters are flawed and everyone gets on with whatever they’re dealt. “There are happy moments but not necessarily happy endings”, he says. It’s a useful parable’.

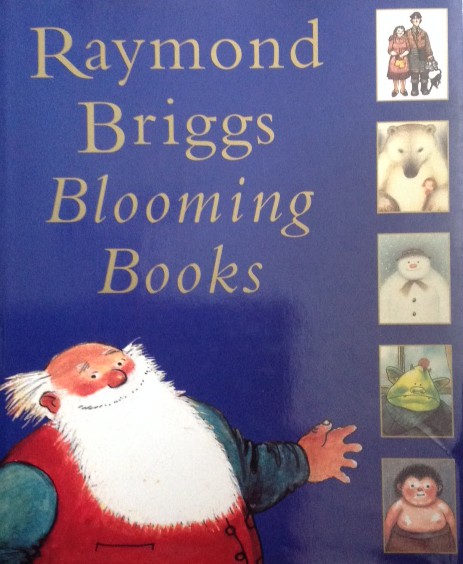

He was born in 1934 and was the only child of Ernest, a milkman and Ethel, a former lady’s maid. He grew up in a small terraced house in Wimbledon and went to Wimbledon Art School at the age of fifteen because he wanted to be a cartoonist. Despite his lifetime love of drawing, this wasn’t an enjoyable experience because he never liked painting. He then did two years of National Service and a subsequent two years at the Slade School of Fine Art. In 1957 he left to become a freelance illustrator and soon found that he liked illustrating children’s books. In the forward to ‘Blooming Books,’ a sumptuously illustrated overview of his prolific work written by Nicolette Jones, he summarises why he could never take to painting:

‘I liked drawing and was good at line and tone. I was also interested in the figure and, above all, what these figure was doing and thinking and feeling. For me, this is the main difference between painting and illustrating. The painter is primarily interested in colour and the shape he is making with the figures; the illustrator is interested in the storytelling aspect of the picture’.

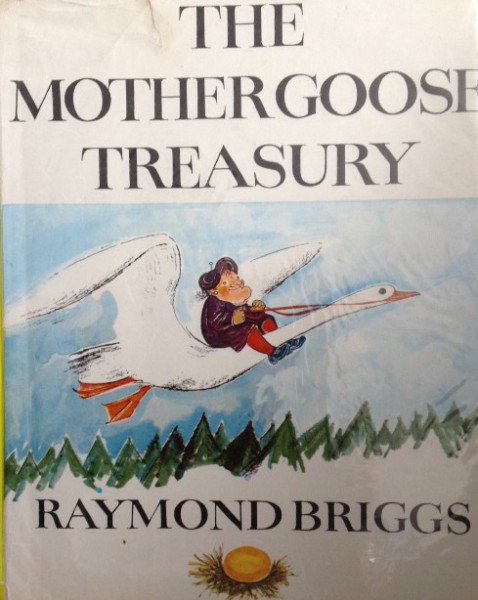

After two years of illustrating work by other authors he decided to have a go at writing his own and published Midnight Adventure and The Strange House in 1962. He also drew detailed pictures for several non- fiction books about architecture and illustrated six stories about real adventurers which Jones described that ‘he did with an energy and speed that owes something to the Italian Futurists’. But his career really took off when he won the Kate Greenaway Medal for the 800 illustrations for ‘The Mother Goose Treasury’ in 1966.

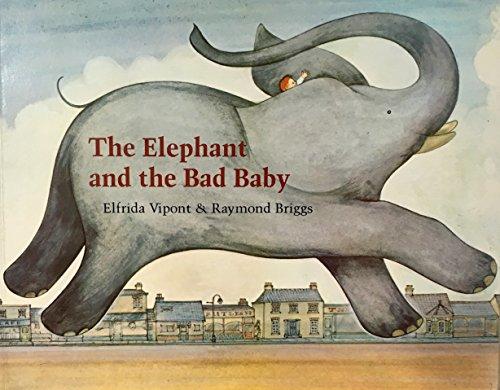

His picture book illustrations are always reassuringly old fashioned and comfortable. When at art school, he apparently liked Dutch and Flemish genre paintings and this influence can be seen in the way he favours rather dumpy, homely figures, a connexion explained by Jones ‘as in Breughel’s pictures , the figures are comical, but there is something dignified about them too’. One of my favourite picture books is ‘The Elephant and the Bad Baby (1969) by Elfrida Vipont which tells the story of how a baby goes on a rumbustious adventure riding on the back of an elephant and encourages him to take a variety of items from shops without payment. As a result they are chased by an increasingly long line of cross shopkeepers who are eventually placated by a tea party at the baby’s house. Jones points out the 1940s period detail that pervades most of the book but’ a fantastical Edwardian ice- cream stall with a moustachioed Italian serving cornets, giving himself licence for blithe anachronism and the use of any visual types he pleases’. This jokey confidence in drawing an almost comic book world is what makes him so distinctive.

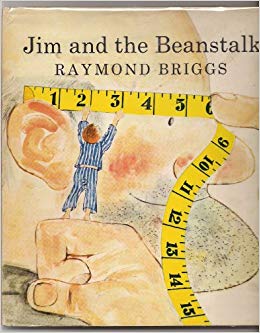

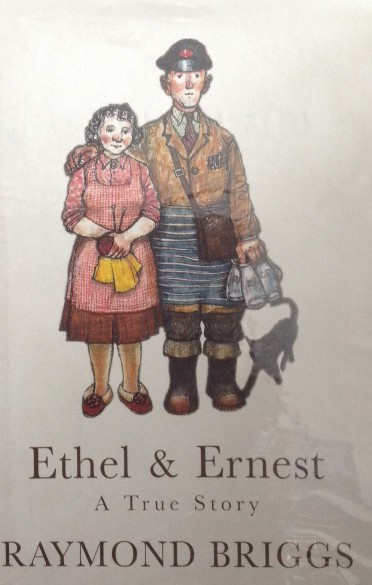

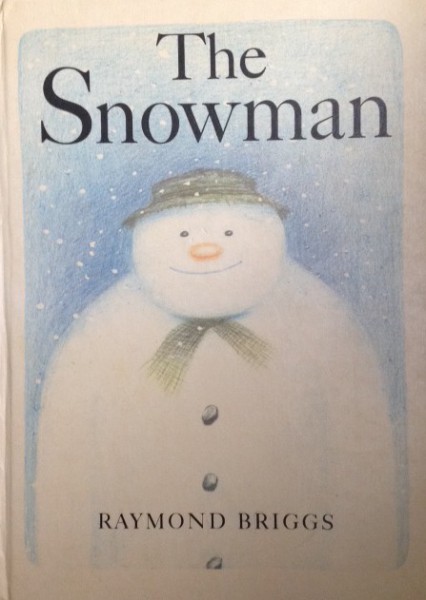

I also love ‘Jim and the Beanstalk’ (1970) which still makes me laugh out loud. Once again he shows us a cheerful slice of realism in the way he depicts the townspeople of the story mixed in with his revised version of the Jack and the Beanstalk traditional tale. Jim is a boy who looks a lot like the nameless character in his future wordless classic ‘The Snowman’ ( 1978) and himself as a boy in his biography of his parents ‘ Ethel and Ernest’ (1998). The giant bears a resemblance to himself as an adult and has some similarities to ‘Father Christmas’ (1973) and other characters in many future books.

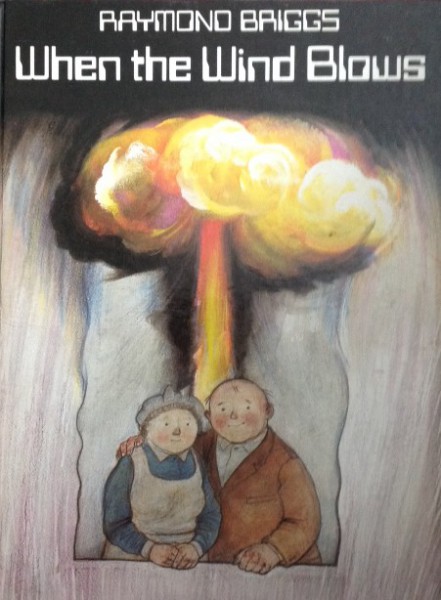

In 1980 he changed direction with the content of his books and his intended audience when he published ‘Gentleman Jim’ which is a gentle satire on the life of the common man. His work became more overtly political and shows the power of pictures in conveying a world view. He is renowned for having a consistent anti- war stance best expressed in ‘When the Wind Blows’ (1982) and ‘The Tin –Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman’(1983). With the publication of ‘Ethel and Ernest’, which many regard as his finest piece of work, he intertwined the personal with the political as he used a detailed strip illustration format to tell the poignant story of his parents and his working class background set against the backdrop of war and the difficulties of growing up on a limited income. As the critic Philip Hensher points out: ‘Briggs using his art not just to entertain but to instruct’.

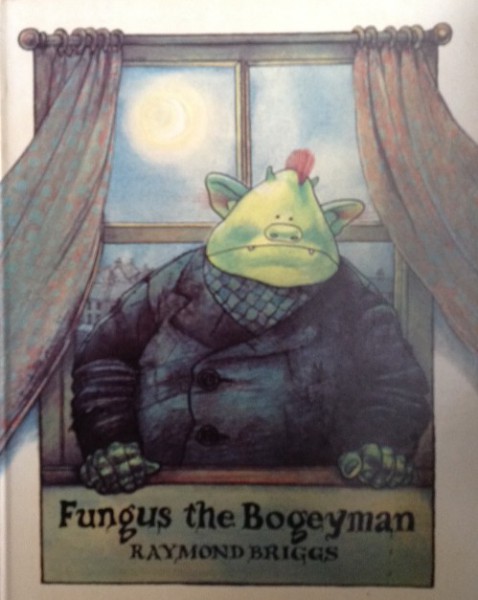

He uses a range of techniques in his illustrations ranging from watercolours in Fungus the Bogeyman’ (1977) and pencil crayons in ‘The Snowman’. He sometimes uses a variety of media in one book as in ink and watercolour to depict the more violent imagery in ‘The Tin- Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman’ contrasted with soft pencil in muted grey pencil to depict grief and loss. Towards the end of this book, he uses mixed media to emphasise the difference between the war- mongers and the victims. He has always enjoyed using the comic book format because as he explains in ‘ The Magic Pencil’ published by The British Council, ‘picture books have a fixed number of pages – usually 32- and that wasn’t nearly enough for everything I wanted to put in’. He tries to keep the spontaneity of his original drawings by photocopying them and then working on the colour. He also admits that he rarely draws from life and likes to invent landscapes.

Writing this piece has made me realise just what an impressive and unusual illustrator he is. So far he has been unpredictable and often controversial in his choice of subjects. He has clearly been influenced by many artists and other contemporary illustrators like Ronald Searle and as a teacher at Brighton School of Art, has also played a part in shaping the style of the next generation of illustrators like Chris Riddell. I have only mentioned a few of his many wonderful books and so I strongly recommend that you read ‘ Blooming Books’ by Nicolette Jones for more in depth information about his life and work. It also contains the full texts of many of his books which makes it a wonderful visual feast for anyone who loves his work.

Karen Argent

July 2018

(Click on any image below to view the pictures in a slide show format)