Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 11 Jun 2018

posted on 11 Jun 2018

Empathy Day Blog Tour – Anna McQuinn Guest Post

( This article originally appeared on the Mr Davies Reads website and is a contribution to Empathy Day on 12th June. It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author.)

In today’s divided world, the need for more empathy has never been more urgent. Helping children to put empathy into action will reduce prejudice and build a caring society. And for me, that means starting with the very youngest!

I believe that even the youngest children are naturally empathetic.

Even small babies are distressed if they see another baby crying, for example.

One of my go-to books when doing outreach in baby clinics and so on is Baby Faces – babies love looking at these almost-life sized photos. But I found even young babies immediately responded with sad faces and sometimes even tears when they looked at this photo of a sad baby.

However, when we as parents or early years workers or teachers come to teach young children about empathy, we often go about it in an awkward way. Who hasn’t heard a mum reprimanding a toddler for hitting another child with a sentence like,

“You wouldn’t like it if Joey hit you, now would you?”

But think about that for a moment – firstly, from a purely linguistic point of view, what a convoluted sentence! All those conditionals! Then think about the imaginative leap we’re asking this toddler to make. He may have felt frustrated at something he couldn’t do/couldn’t understand… and lashed out. But now we’re asking him to imagine another child feeling that thing that he himself can’t understand, to imagine that child lashing out and – to imagine he was on the receiving end!

So how to go about encouraging empathy in our littlest citizens?

I think they are capable of great empathy– but it’s about giving information on that other person’s needs so they don’t have to turn emotional somersaults to slip into another’s shoes. It’s about helping them to make that imaginative leap in an unconvoluted way. Stories are an ideal way of doing this.

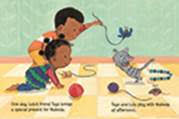

That’s what I tried to do in Lulu Gets a Cat. Lulu really wants a cat, but her mum is nervous that Lulu doesn’t understand what is involved. So Lulu and her mum read stories about cats, they read about how to care for cats and Lulu practices on her toy: feeding, cuddling and playing with it every day (and marking it off on her chart).

Once Mum is convinced Lulu is ready, they research adopting and head off to the nearest cat shelter to get one.

At this point in the story, as at this point in real life, most young children would expect to taken the chosen kitten home. But Jeremy explains that moving is stressful for cats and that Lulu needs to prepare by getting the kitten’s favourite food, and making a corner with a bed, food and litter tray close together where the kitten will feel safe.

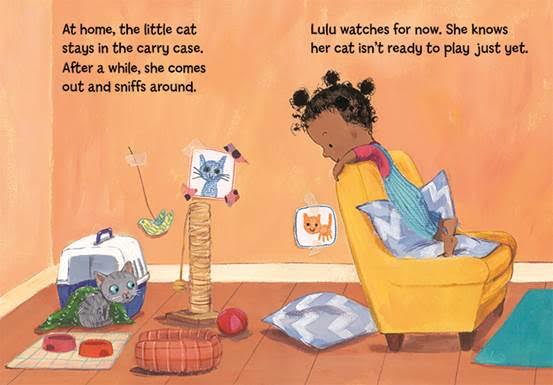

Once everything is in place, Lulu and Mum head back to the shelter to collect the little cat and take it home. Once again, at this point in the story, most young children would by just dying to stroke and cuddle and play with the new kitten. But once again, Lulu hangs back. Based on her reading she knows the little cat is afraid and needs time to explore.

This for me is the most powerful image in the story – Lulu is able to act on her empathy to put her little cat’s needs first.

Studies show that relating imaginatively to book characters builds real-life empathy skills. When you get lost in a book, your brain lives through the characters at a neurological level. Fiction tricks our brains into thinking we are part of the story. So, the empathy we feel for characters wires our brains to have the same sensitivity towards real people.

So, Lulu has gained insights into her cat through her reading of both stories and research into cat care. But, as Robin Banerjee explained in a speech given at the Bookseller Children’s Conference in 2017, empathy “is not about encouraging children to be completely wrapped up in other people’s feelings, becoming biased and ‘emotional’ instead of rational and objective. In fact, empathy is pretty complex. Of course, there is an important emotional dimension to it, but we also need to think about how children are actually behaving, how they are thinking (cognition), what goals are driving them (motivation) , and what their social relationships are like.”

Banerjee explained that there are at least three major aspects of empathy:

- One part of this is how you react emotionally to other people’s displays of emotions – such as fear, or distress, or indeed positive emotions such as happiness and joy.

- Another part is the accuracy and depth of your cognitive insight into other people’s thoughts and feelings – how are other people (who might be quite different to you) likely to see and experience the world?

- And third – quite crucial as it turns out – is what youactually do with those emotional and cognitive reactions: things like comforting, helping, and supporting others.

The translation of empathic thoughts and feelings into behaviour requires a motivation of care and compassion within one’s relationships.

We can see clearly that Lulu has developed not just empathy for her new little cat, but cognitive insight into the cat’s needs. She builds on this and is motivated to manage her own impulses (even though they are loving ones) so she can hang back and allow the new little cat to settle before Lulu cuddles her.

I believe passionately in the power of stories to not just help children empathise and understand others, but to act on that to engage with others in a sensitive and understanding way. So how could I not end the story but with Lulu sharing a book with her new friend – and the hope that in reading this story, other children will learn the power that empathy has to change lives.

Anna McQuinn

June 2018

(Click on any image below to view them in a slide show format)