Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 20 Apr 2018

posted on 20 Apr 2018

Percy F. Westerman: boys adventure stories and colonial dreams

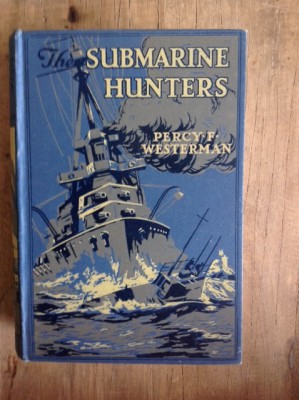

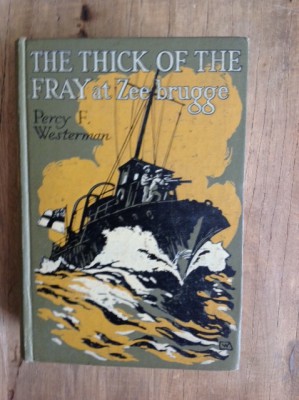

Percy F. Westerman wrote ripping yarns for boys at an almost incontinent rate. Between 1908 and 1959 he turned out the best part of 180 books – which even my crummy maths tells me is just a tad over three a year. I sometimes come across his stuff in second hand bookshops or junk shops and quite often they are pretty wrecked – a combination of being read voraciously and the cheap production values the publisher obviously insisted on – but his earlier books in particular are redolent of a sort of timeless Edwardian British colonialism and triumphalism that can be unpalatable from a modern perspective.

His books are meant to be page turners and old fashioned adventure – tales of derring-do – but, taking the most charitable line of criticism, they tend to reflect ideas of their day that might make a modern day reader look askance. His assumptions that a white British man is in every way naturally superior to any foreigner of any colour, religion or gender are precisely the kind of ideas that get you removed from library shelves.

Even so, that’s not to say he doesn’t have his champions. Back in 2013, Derek Brown, writing for The Guardian declared himself a dedicated Westerman reader. He describes his devotion in this way:

"It was tosh, of course, quaint old fashioned tosh. And it took him to the top of the tosh tree. He dominated the latter half of a golden age of popular juvenile fiction; an age which was made possible by a combination of cheap printing and universal literacy, and which was killed by rising costs and television.

The boys of Westerman's time, and in his particular market, had no television and little money for the cinema, let alone travel. They lived in an age when scientific and engineering achievements were exciting rather than alarming. Westerman shared and stimulated that excitement, with splendid yarns set in exotic places, and stripped of the pious overlay of his Victorian predecessors."

When I read this it struck me that something quite important was being said by Brown. His case for writers like Westerman is that they are not trying to evangelise the values of Empire; they have no need to because they take those as read, as fundamental to the very fabric of the British-centric view of the world. Free from the burden of having to justify or extol British values to a hostile or sceptical world, Westerman was able to focus on the simple issue of storytelling – which is something he took on with relish.

What Brown also claims is that Westerman wrote for what he calls ‘ordinary lads’ with no real concern for style or for experimentation. These books were for boys whose parents couldn’t afford top-draw editions and who in any case didn’t give a fig for elegant, thoughtful, three-dimensional stories but just wanted an exciting romp. I’ve personally tried to read some chunks of stuff from the three of his books picture below and I can attest to the fact that in stylistic terms it is some of the very worst writing I’ve struggled with.

But, in this respect Westerman is not really that different from other popular material being pumped out at the time and it feels as if he belongs to the kind of writing that found its natural home in boys comics like The Eagle, Valiant or Hornet where brave Britons were constantly fighting one war or other, catching treacherous foreign spies or being unfeasibly good at sport.

These adventure books were the Young Adult fiction of their day and speak more eloquently than almost any other piece of social historical evidence about just how much the interests and expectations of young readers, children’s book authors and the wider society have changed. I was tempted to say that these were more innocent times but that’s a silly and meaningless cliché – in truth Westerman was part of a social propaganda machine that kept the values of Empire in the eyeline of a new generation of children. The fact that those messages of British superiority could be delivered subliminally through these stories reveals them as an important ingredient in the cultural reproduction of ideas relating to our deep-seated belief in the fundamental iniquity of foreigners. This is, of course, a set of ideas that continues to play its part in public debates about British identity today. So maybe, in a perverse way, the likes of Percy Westerman and his stories of gung-ho adventuring have remained more influential than we’d like to admit.

Terry Potter

April 2018

( Click on any of the images below to view them in slide show format)