Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 26 Mar 2017

posted on 26 Mar 2017

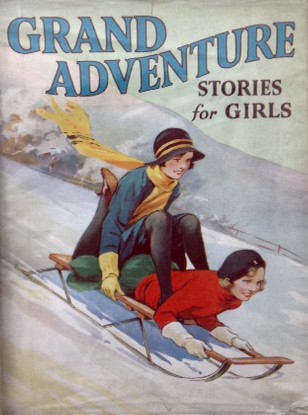

Girls’ Annuals and Story Books – Built To Last

I don’t know if children had much bigger stockings in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain but it seems likely any young girl waiting for that traditional Christmas gift, the Annual, would need something pretty robust to hold the behemoth that would be coming her way. In most second hand bookshops – and a good many second hand junk shops – you wont have any difficulty finding pre-First World War annuals aimed at both boys and girls. All of them are enormous, densely printed with stories, educational materials, practical tips and general exhortations to health, well-being and patriotism. And they are largely unloved these days – hard to sell, partly because they are so huge, cheaply printed and seemingly irrelevant to modern lives. They don’t even seem to have nostalgia value any more as the generation that would have read and loved them have now largely passed away.

So why were they such massive things and very different to the late twentieth century and modern day annual? I think the clue lies in the name – annual. These were books, almanacs almost, that were meant to last and sustain the reader over a whole year – available to refer back to and dip into at leisure on a rainy day or a school holiday. After all there was no television, no internet and no electronic games to divert the bored child. Today’s annuals are more a celebration or badge of membership of a ‘club’ of devotees wanting to identify themselves with whatever is topic of the annual.

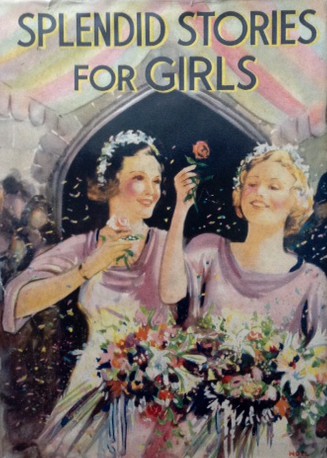

The content of these annuals is highly gendered and the covers are unambiguous in their differences. In many ways the boys’ annuals are much more obvious in their content and the subliminal messages are far easier to decode – being a boy means being interested in sport, war, doing the decent thing, handicrafts and becoming the family bread-winner, the protector. The girls’ annuals on the other hand are far more complicated and interesting.

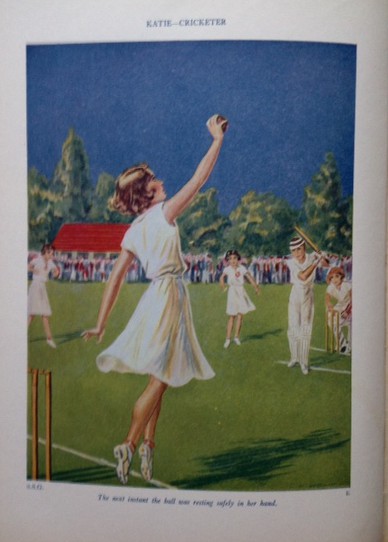

There are, of course, the simple messages – a focus on sensitivity, household skills, cooking and, rather coyly, matters of the heart. But many articles go well beyond this, covertly and archly raising questions about what it is that girls can do or perhaps what they should be allowed to do. Girls are allowed to do ‘boyish’ things – play sport, make things, be interested in the mechanical or the politics of the outside world – but only up to a point. Girls, the annuals and story books seem to be saying, need to get some of their youthful zest off their chests before they knuckle down to being good wives and child-bearers. Give the young fillies their head for a while, it wont be a lasting phase, and then they’ll be happy to settle down and marry.

I think that because these enormous annuals and story books have largely bitten the dust it’s easy to underestimate their significance. These books were compiled with what strikes me as a clear strategic purpose - to be covert ‘training manuals’ for the younger generation - and in this goal I think they are remarkably successful. The entries are written either anonymously or by a mix of men and women often writing under pen names that disguise their real gender. Some of these authors are cunning at smuggling in defiant political messages echoing the ideologies of the adult world significant for teenage girls – especially the issues of equality and suffrage.

As someone who has spent a lot of my professional life studying sociological theories of one kind or another – and being utterly perplexed by many of them – I would always point someone wishing to study issues relating to first wave feminism to these Girls’ Annuals and story books. A bit of simple discourse analysis on these texts will yield plenty of fascinating and valuable examples of how the patriarchy maintained its dominant hold on gender politics.

You probably wont need more than one example in your collection because they pretty much all follow the same formula. But if you’re interested in children’s literature and the social significance of this body of work, you really should have one on your shelves.

Terry Potter

March 2017