Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 02 May 2016

posted on 02 May 2016

A different generation of novels for Young Adults

The market for novels aimed at the YA or ‘young adult’ audience has been one of the fastest growing areas over recent years. There has been a substantial reassessment of the reputation of many of what are now seen as post-war ‘pioneers’ of this genre and modern exponents are more highly valued than ever before and are even the subject of study at exalted academic levels.

However, it would be a mistake to think that the YA is exclusively a phenomenon of the modern world. Books aimed at the 11-16 age group were also a key part of a child’s upbringing in the late Victorian and Edwardian Britain and which endured in some incarnations right through the inter-war years. It’s worth saying at the outset that most of these books were targeted pretty exclusively at a middle and upper middle class audience – partly because of the cost of these books, the literacy levels they demanded but also because of their content.

A substantial body of academic research now exists which has analysed this first golden age of the YA novel and there are some consistent themes which emerge from this body of work. Firstly, and unsurprisingly, these books are primarily tools of instruction – not in the sense of a text book for use within a curriculum but as a contribution to the socialisation of children. They deal directly and indirectly with issues of gender and address issues of what activities it is appropriate for boys and girls to get interested in – for girls the subject of family, marriage and friendship feature prominently while boys are fed a diet of exploration, war and competition.

These books are also concerned with Britain’s status as a colonial power. The tradition of the stiff-upper-lip and the ‘white man’s burden’ feature prominently and the British boy is repeatedly exposed to tales that emphasise the superior moral and intellectual prowess of the average British man abroad – as well as reassuring him of his capacity for heroism and the British boy's innate instinct for bravery when faced with danger or threat to his honour.

There is also a clear set of implications around the nature of the type of education most likely to produce the superior boys and girls of the future. Private educational establishments dominate these books and there is often a sense of an unbroken line from Prep to University – usually or preferably Oxford or Cambridge. As a result the school-centred novel for both boys and girls is extraordinarily popular and this is something that endures even today. Without these early YA novels of the public school setting out the rules of the genre the runaway success of the Harry Potter series in the current millennium would have been unlikely. The conventions of the public school story have clearly entered the cultural consciousness at a level which allows J.K. Rowling to use them safe in the knowledge that they would be immediately understood by the current generation of readers.

Obviously, some of these early YA books are better written than others – although I have yet to personally find any that I would read other than for the purposes of finding things in them to scream about. They are, in my experience, generally so reactionary that it’s hard to even take them seriously – their levels of casual racism, sexism, homophobia and scorn for the disabled seem so strikingly upfront that it’s hard to read them as anything but self-parody. I don’t personally think it’s right to condemn writers from a previous age for not having twenty-first century sensibilities and no-one in their right mind might expect them to have a sophisticated awareness of what we now call political correctness. However, having said that, these books are manuals of class domination and many revel in attitudes that would have been regressive in a Stone Age culture and are oblivious to many of the more progressive political, social and cultural ideas that were doing the rounds when these were written.

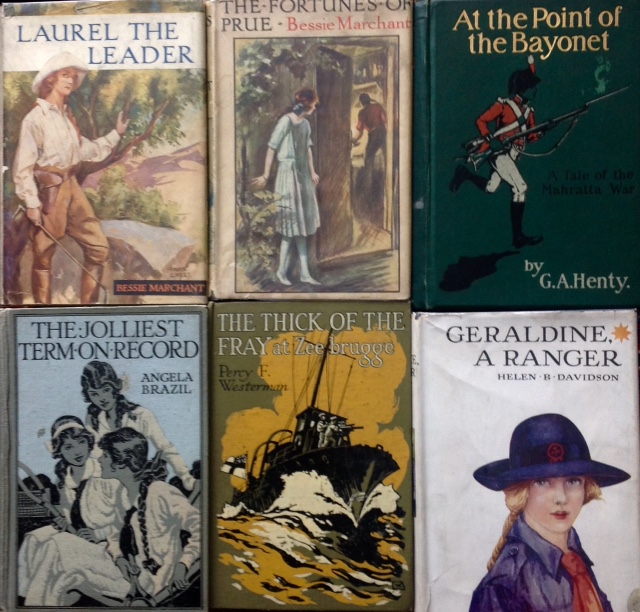

Having said that, I still think they are important social documents for anyone wanting to understand the sort of messages a young adult audience of the late 19th and early 20th century would have been exposed to. It’s hard to understand the way ideas of gender, ethnicity and cultural difference were reproduced without understanding what sort of notions are trapped between the covers of these books. Which brings me to the topic of the increasing difficulty of finding copies of these books in their original condition.

Because these books went through a period of being pretty much dismissed as disposable dross from a bygone age many have been sent off to be pulped or allowed to fester and rot in some damp basement. They were also seen at the time of publication to be essentially ephemeral items that would be discarded as the child grew up and, as a result, the production values and the quality of the paper used was often pretty shoddy and added to the chances that they wouldn’t survive today. So as time goes by these little windows on the world of the Victorian and Edwardian child are being lost – which is, I think, a shame. Prices for these books are edging up now, especially those with a good cover still intact, and I can only imagine that process will continue as they become increasingly rare.

If you’re interested in this little bit of social history, it would be wise to get in there soon while you still can.

Terry Potter

May 2016