Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Aug 2025

posted on 14 Aug 2025

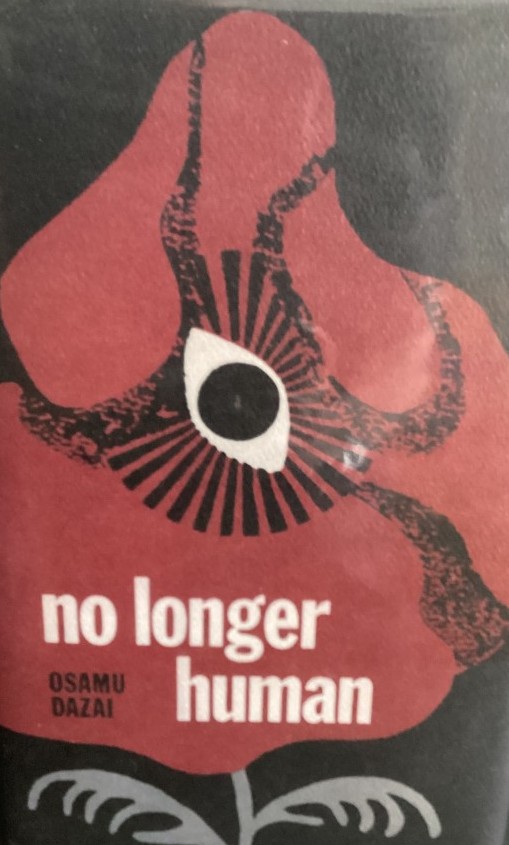

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai

First published in 1948, you will probably see a number of reviews that refer to Dazai’s novel as a classic of Japanese 20th century literature but, in many ways it’s really a bit of an outlier when taken alongside other translated Japanese novels of the first half of that century. Unlike the classically structured or formal aesthetics favoured by the likes of Kawabata or Mishima, Dazai favours a more visceral dip into the physical and emotional underbelly – a journey into one man’s hell.

The story is essentially the journal, a set of notebooks, of one man, Yozo Oba and his first-hand recounting of a life lived very badly indeed. An unnamed narrator provides us with a prologue and epilogue to these notebooks which are reproduced in full to make up the narrative told by Yozo himself. Our anonymous narrator also tell us that he’s in possession of three photographs of Yozo from different stages of his life and we discover from these that his path through the years has been traumatic. We are told of the final photograph:

“I think that even a death mask would hold more of an expression, leave more of a memory. That effigy suggests nothing so much as a human body to which a horse’s head has been attached. Something ineffable makes the beholder shudder in distaste.”

The life story told in the notebooks is of an individual who comes to see himself as almost beyond redemption – a boy who becomes a man and a man who arrives at a point where he can be considered so physically and emotionally degenerate that he is, in his own eyes, ‘no longer human’. As a child he takes on a persona of the clown to win acceptance and favour – but he’s always aware that this is a mask he’s consciously crafted to bring him favour. There are indications that as a child he may well have been abused by the house servants and the longer-term relationship with his father and with other authority figures is problematic.

We follow him through a descent into a life where he uses friends – men and women – unscrupulously, takes advantage of his physical good looks but gets drawn into drug and alcohol misuse. Those he thinks of as friends turn out to be manipulators themselves and the rift with his family becomes unbridgeable.

It’s certainly true that the picture Yozo paints of himself is of a man beyond sympathy, a man bent on his own destruction and unfeeling about those he’s happy to take down with him. But the story is much more subtle than that and we are ultimately left to consider just how much we can really trust the portrait he’s drawn for us. The photographs we are told about in the prologue lead us to suspect that this is indeed the true and uncensored record of the terrible life of a dissolute, amoral creature - but are we just trapped inside this man’s own perverse view of a life built around self-loathing?

Dazai underscores this ambiguity in his epilogue when the unnamed narrator who has presented us with the notebooks of Yozo’s tells us:

“ I never personally met the madman who wrote these notebooks. However, I have a bare acquaintance with the woman who, as far as I can judge, figures in these notebooks as the madam of a bar in Kyobashi.”

And what does she tell us? Well, quite a different story. The final words of the book are hers too:

“The Yozo we knew was so easy-going and amusing, and if only he hadn’t drunk – no, even though he did drink – he was a good boy, an angel.”

There are a number of translations of the book available (some very hard to find) but the one I read and features here is the reissue by New Directions and is translated by Donald Keene.

Terry Potter

August 2025