Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Jul 2025

posted on 08 Jul 2025

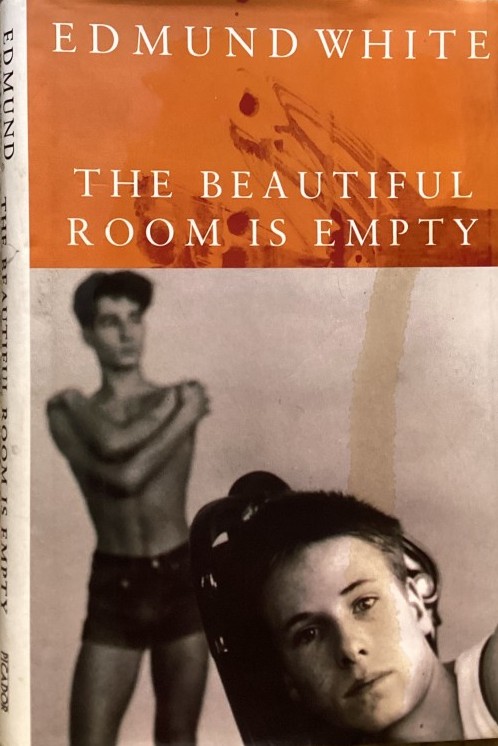

The Beautiful Room is Empty by Edmund White

Looking for my own small way to commemorate Edmund White’s death on the 3rd June, I returned to The Beautiful Room is Empty, the second in a trilogy of autobiographical novels which began with A Boy’s Own Story (1982) and concludes with The Farewell Symphony (1997).

When I last wrote about these early novels I was fairly disparaging about the first one. But the second is a richer and more accomplished work all round. Not only have the earlier faults of over-writing and occasional clumsiness been ironed out, it is also on a more ambitious canvas: while the sexual awakening of White’s alter ego remains centre-stage it is as much concerned with intellectual, cultural and political self-discovery and consequently is more convincingly alive than its predecessor.

It opens with the narrator struggling through the final terms at his Midwestern prep school in the late-1950s, where the art school across the street is infinitely more interesting, pulsing with the bohemian life of young artists – all just a few crucial years older than the narrator. He starts skipping classes to go over to the art school to hang out in the warren of bitterly cold studios. Here he meets Maria, a bisexual, communist painter who becomes a sort of platonic lover, and who introduces him to a glamorous underworld of rebels, obsessives and eccentrics. A local bookstore operates as a focal point for what we might once have called ‘the alternative society’ and here he meets the owner, Tex, gay, impoverished, weighed down with debt and the worry of keeping his store open, but thrilled by new books, new ideas – thrilling messages from the world’s intellectual capitals. The first copies of Colin Wilson’s much-lionised study of existential rebellion, The Outsider, arrive and they spend days breathlessly reading bits to each other.

At university in Chicago the narrator is introduced to Lou, a key character, a gay heroin-addict and advertising copy-writer in his thirties who for a period becomes his lover, guide, mentor and guru. I hadn’t previously recognised what a Burroughs-like figure Lou seems to be – whether in homage to William Burroughs the man or to the hallucinatory inventiveness of Burroughs the writer, I’m not sure. They move to New York to scavenge a life on the margins of the artistic-literary world.

What we get, then, in this roman à clef is not just the dawning of White’s own queer consciousness but also a growing understanding of what it is to be gay in the wider world – and of what a world accepting of queerness might one day look like. White would go on to elaborate his ideas of queer literature, culture, politics and aesthetics more fully elsewhere, but these early novels documenting gay life in the 1950s and 60s are still disconcertingly prescient in the way they reach towards the wider struggles for gay emancipation that were just over the horizon.

The novel closes with the gay customers of the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village finally rising up against oppressive policing and brutality. The following morning the narrator rushes out with Lou to buy newspapers and see what the world is saying about the Stonewall Uprising: ‘But we couldn’t find a single mention in the press of the turning point of our lives,’ the novel concludes.

And yet despite the oppression and prejudice of the time White is writing about I still get the impression that he always found something to relish, even when consumed by self-loathing, the desire to be ‘cured’, to conform to heterosexual ‘normality’. Yes, there is a sense of historic suffering and outsiderhood, a similar pressure-cooker atmosphere to that we get in Ginsberg, Genet and Burroughs, but there is epiphany and exhilaration and joy too.

Edmund White wrote of the queer experience in a prose that few other writers could hope to match and in a voice that seemed characteristic of another age – fearlessly candid and honest, but also consistently free of cliché, sanctimoniousness and political correctness. He was a true original and perhaps more importantly an originator. The beautiful room may be empty but thankfully I don’t think White’s ruthlessly honest, erudite, mischievous, gossipy presence will ever leave it.

Alun Severn

July 2025

Edmund White elsewhere on Letterpress:

Rereading Edmund White (again)

The Unpunished Vice: A life of reading by Edmund White