Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Mar 2025

posted on 19 Mar 2025

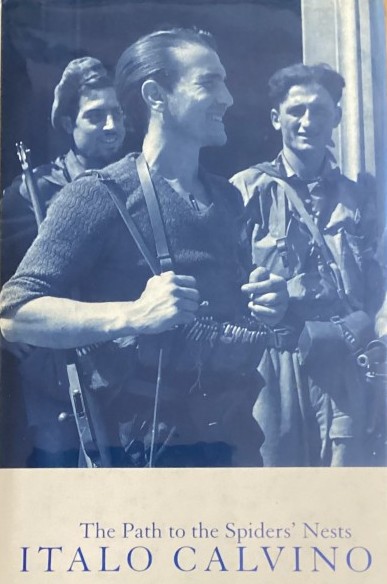

The Path to the Spiders’ Nests by Italo Calvino

Writer, journalist and literary critic, Italo Calvino (1923 – 1985) is perhaps most associated with that generation of post-war European public intellectuals who embraced what is broadly described as post-modernism – a school of thinking that fundamentally challenged the traditional or formal structures of narrative novel writing.

But there are those commentators who believe that Calvino’s sensibility remained deeply informed by what became known as ‘neorealism’ – a conscious attempt to capture the concrete reality of life as it is lived, especially by those on the margins who might otherwise be voiceless. The Path to the Spiders’ Nests, Calvino’s first novel published in 1947 rather supports this assertion being avowedly neorealist in form and intent.

The older Calvino however repudiated this early work despite its success – refusing requests for it to be reprinted for the best part of a decade. A second edition finally appeared in 1954 and then later in 1964 he sanctioned a ‘definitive’ edition that included a substantial foreword of his own that explained why he felt he needed to distance himself from the neorealist approach to writing and itemising what were, he believed, the flaws in the book.

The copy I have read here is the new 1998 translation by Martin McLaughlin that takes into account the changes Calvino insisted on, previous translation errors and what McLaughlin calls “(sections) that had been silently censored in the English version.”

The novel itself takes us to a small town in Italy during the Second World War where we meet Pin, a young boy of indeterminate age (he could be anything from 9 years old to 12 or 13) who lives in poverty in the same house as his sister, a prostitute often catering to the occupying German soldiers. Pin is precocious but also unworldly and naïve – he is desperate for positive adult approbation and spends his time hanging around cafes and bars where he tries to entertain the locals. His big fascination is with the Partisans who are attempting to fight the Germans – it’s an adult ‘club’ he wants membership of.

To curry favour with the local Partisans he contrives to steal a German pistol from a soldier visiting his sister and he takes it off to a special hiding place – this is the place of the spiders’ nests, a place out of town only known to him where these unusual spiders make their home. He resolves that he will not reveal where this hiding place is until he meets an adult who he can trust.

Pin finds himself arrested by the Germans for the theft and while in prison he meets an older teenager known as Red Wolf who is already something of a legendary figure. Red Wolf takes Pin under his wing and together they escape making it to the Badlands where Pin’s life in a Partisan cell begins.

Pin continues to boast of his possession of the gun he stole but continually refuses to reveal where his hiding place is – he is constantly seeking the adult who he can trust and, implicitly, seeking the love any child needs.

The second half of the book deals with Pin’s time with the Partisans and it details the rather sordid reality of the life they live. The story strips the Partisans of any glamour – they are covered in lice, poorly resourced, duplicitous, deceitful and (some of them) cowardly.

I don’t want to reveal the denouement because it would be something of a spoiler but I don’t think it’s too much to say that all this will of course eventually take us and Pin back down the path to the spiders’ nests.

I am very much more a fan of neorealism than I am of post-modernism and so Calvino’s novel – disappointing to him – was very much to my taste. I found it absorbing, atmospheric and ultimately touching. Some critics have suggested that this is a ‘coming of age’ novel but I would disagree with that sort of assessment – this isn’t about a boy discovering the truths about growing into an adult world, it’s a book about what war does to children who are robbed of love and security. Seen that way, this is a searing condemnation of war.

Paperbacks are available for well under £10 and the rather handsome Cape hardback pictured here isn’t too punishing.

Terry Potter

March 2025