Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 17 Mar 2025

posted on 17 Mar 2025

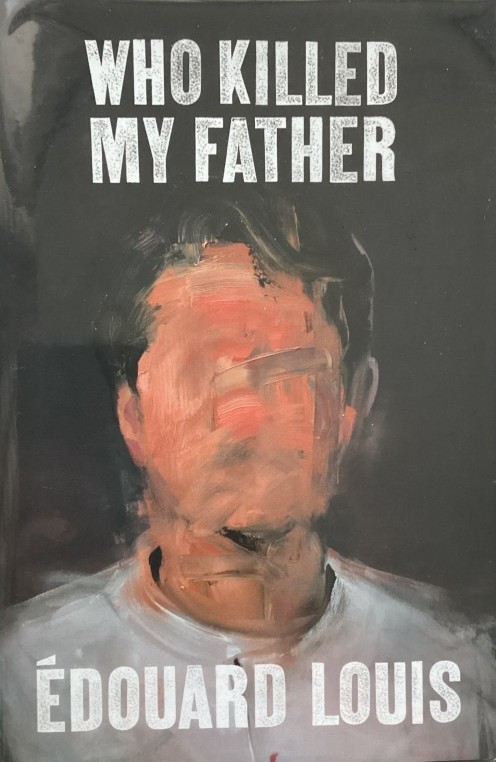

Who Killed My Father by Édouard Louis

When I picked up this slim book, I have to be honest and confess that the young French author, Édouard Louis was a new name to me, But the synopsis of this 2018 book hooked me in:

“Who Killed My Father is the story of a tough guy – the story of the little boy I never was. The story of my father.

In Who Killed My Father, Édouard Louis explores key moments in his father’s life, and the tenderness and disconnects in their relationship.

Told with the fire of a writer determined on social justice, and with the compassion of a loving son, the book urgently and brilliantly engages with issues surrounding masculinity, class, homophobia, shame and social poverty.

It unflinchingly takes aim at systems that disadvantage those they seek to exclude – those who have their expectations, hopes and passions crushed by a society which gives them little thought.”

A little bit of further nosing around on the internet – Wikipedia in this case – cemented my view that this was something I’ve missed out on:

“The work of Édouard Louis maintains a fine link with sociology: the influence of Pierre Bourdieu pervades his novels, which invoke the themes of social exclusion, domination, and poverty... The influence of William Faulkner is also revealed through Louis' superposition in the same sentence of various levels of language – placing the popular vernacular at the heart of his writing… Louis' novel Histoire de la violence contains an essay on Faulkner's novel Sanctuary.”

And although the book is regularly referred to as a ‘novel’, that is a hopelessly inappropriate way of describing what is some part memoir, some part confessional, some part sociological exploration and some part political diatribe. And all packed into 80 compellingly written pages.

Structured as a letter from a gay, university educated young working-class man to his reactionary, at times brutal and now debilitated, dying father, the book is an attempt to understand their relationship (or lack of it) and a sort of benediction to his violent father who Louis maintains is a victim of a social and economic system that has kept him in a position of exploitation and misery.

Louis, who grows up flamboyantly gay is bullied by everyone in his community – at school by his peers and at home by a father who is ashamed of him. As soon as he can, Louis leaves and the distance he puts between them enables him to look back and understand that his father’s repellent right-wing views come from the way he’s been bent out of shape by social forces and deliberate political policies. Now, crippled by a work accident and unable to really look after himself, this broken man is a shell of a human being. What, Lois asks, has brought him to this pass?

Louis doesn’t hold back on pointing the finger of blame at the political hierarchy and isn’t frightened to name names. Tim Adams, reviewing the book in 2019 for The Guardian, puts it this way:

“… Louis names and shames those successive presidents and their ideologies that have stripped hope from his father, and left the family so threadbare: Jacques Chirac, who “destroyed your intestines” by withdrawing subsidy for medications for chronic conditions; Nicolas Sarkozy, who skewered his father’s self-worth first with a campaign against “les assistés” (the “skivers” and “scroungers” of the austerity lexicon) and who then “incentivised” him back to work as a street sweeper after his disability benefits were cut; François Hollande, who relaxed regulation to allow employers to extend his father’s hours; and finally Emmanuel Macron, who reduced housing subsidy by a critical five euros a week, while reducing taxes on the rich.”

Louis’s breakthrough novel, The End of Eddy, in 2014 began to develop the same themes of working-class alienation and exploitation and this short book picks up those issues and drive them home like a nail smashed into a plank of wood. It’s not subtle but I found it quite thrilling.

Available in paperback and you can expect to pay well under £10 for a copy.

Terry Potter

March 2025