Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 02 Feb 2025

posted on 02 Feb 2025

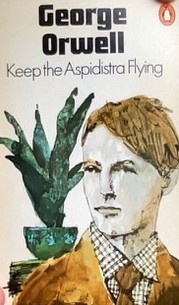

Keep the Aspidistra Flying by George Orwell

The first book I read by George Orwell was Keep the Aspidistra Flying and that was almost fifty years ago. For this reason it is a book I have always regarded with great fondness – but as it turns out have remembered less than accurately.

But Keep the Aspidistra Flying was a novel that Orwell himself felt he should never have written. This is confirmed in a number of his letters, but especially in one written in 1946 replying to his friend George Woodcock. Orwell says that he knew the novel was a failure but that at that time had had no other book in him and desperately needed the £100 or so that a new work might bring in. Woodcock must have asked to borrow the book because Orwell goes on to explain that he no longer has a copy, having given away the one he bought in a secondhand bookshop. During his lifetime he refused publishers’ requests to reprint both Keep the Aspidistra Flying and the novel that preceded it, A Clergyman’s Daughter.

The hero – or rather, anti-hero – of Keep the Aspidistra Flying is Gordon Comstock, not yet thirty but ‘already motheaten’, the last surviving male Comstock in a middle-middle class family brought low by genteel poverty. Gordon is a would-be poet (one published ‘slim volume’) who barely keeps body and soul together from what he earns working in Mr McKechnie’s bookshop and subscription library (it very closely resembles the actual Hampstead bookshop Orwell had worked in a few years earlier).

Gordon has walked out of at least two better-paying jobs that family connections had eased him into because he can’t stand the hypocrisy and banality of ‘business life’ – the false respectability (the aspidistra in the window), the sucking-up to the bosses (the cowed clerks and underlings who live in fear of losing their jobs), the ingratiating middle-managers, the philistine world of blow-hards and bullies and braggarts. For Gordon has declared ‘war on money’ – on the ‘money-world’, the rich, the ‘Upper Crust’, the ‘the pink-faced masters of the world’. And his primary weapon in this war is punishing self-denial – denying himself money, rejecting comfort, living in squalidly respectable middle-class digs in which he makes illicit cups of tea in his bitterly cold room, sneaking the tea leaves down the toilet when his snooping landlady’s back is turned.

But I realise now that all those years ago I rather misread the novel, automatically assuming Gordon Comstock to be a lightly satirised alter ego of Orwell’s – an anti-hero, certainly, but one held in affection. I think I probably also regarded the novel as essentially comic – and it is true that there are moments of humour, but they are dark, bitter moments and most typically involve outrageous Orwellian outbursts of prejudice or disgust or both. In fact, I think Orwell loathes the character he has created and holds him in utter contempt, because Gordon has entered a war which he has neither the courage nor the political analysis to see through. His protest is a lone one, uninformed by any sense of collective political action that might change things, and deep inside he continues to crave the respectability and acceptance that money bestows. But perhaps more importantly – although this is only my speculation and many will probably consider it absurd – I think Orwell loathes Gordon Comstock because he embodies all of Orwell’s worst fears about himself: his own shameful weaknesses, his own hypocrisies, and the possibility that he too may fail in his own struggle against class and wealth and privilege.

But sadly, as interesting as this background context may be, Keep the Aspidistra Flying is a poor novel. Gordon’s all too frequent embittered interior monologues are grossly repetitive (intentionally so, no doubt) and there are long passages in which any sense of forward momentum in the narrative is lost. Worse than this, the only character who has any sort of presence on the page is Gordon. The others – his care-worn sister, Julia; his dreadful snooping landlady, Mrs Wisbeach; his friend, Ravelston, the wealthy editor of the small left-wing literary journal that occasionally publishes his poems; even (in fact, especially) Gordon’s girlfriend, Rosemary – they are all merely ciphers and one reads about them without for one moment the slightest feeling that they have any real existence as flesh-and-blood characters.

There are a few episodes in the novel that are done well and where the story begins to come properly alive – the description of Gordon and Rosemary’s day out in the country and the damp, pretentious riverside hotel they lunch at; an appalling, extravagant debauch during which Gordon blows his windfall from a Canadian magazine that has unexpectedly published one of his poems; and perhaps the final pages which I won’t reveal because it will spoil the story – but they stand out partly because of the flatness that surrounds them.

I revisited Keep the Aspidistra Flying because I had such fond memories of reading it and of first discovering Orwell’s work, but I must say that this time round I found it sour and disappointing. Even so, I’m glad I reread it and (perhaps perversely) would still recommend it: it may fail as a novel but for the other things it tells us about Orwell and his life and times I think it remains an essential part of the picture.

Alun Severn

February 2025

Orwell elsewhere on Letterpress:

There are numerous Orwell-related articles on Letterpress and all the links can be found in this digest.