Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 04 Dec 2024

posted on 04 Dec 2024

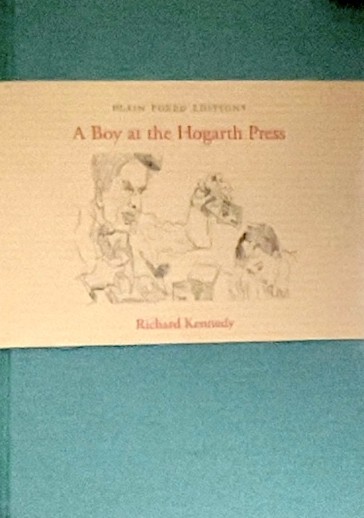

A Boy at the Hogarth Press & A Parcel of Time by Richard Kennedy

Richard Kennedy’s charming and beautifully illustrated memoir, A Boy at the Hogarth Press was previously reviewed here on Letterpress back in 2017. I’m revisiting it now not because I disagree with anything in that review but because since it was written the memoir has become available in a new edition from the small independent publishing house, Slightly Foxed, and importantly is paired in a single volume with Kennedy’s later childhood memoir, A Parcel of Time.

The 2017 review quite rightly noted that there is something reminiscent of George and Weedon Grossmith’s Diary of a Nobody in Kennedy’s memoir – a slightly similar Pooterish tone. This is perfectly true and this apparent artlessness is part of the charm of the book, I think. But when you read both memoirs together I think something very different emerges.

The slightly later A Parcel of Time (1977) has a very different emotional tone. It is dominated by Kennedy’s memories of the First World War – the death of his father and three uncles on active service, his mother’s grief, the crowds of troops moving through the various south-east coastal towns where they rent houses, his lack of friends and loneliness. His mother is increasingly unstable and despairing: her husband’s death has shackled her to a bewildered young son she scarcely seems to know and secretly wishes had never been born – and she tells him this; her own upbringing – she was a child of the Raj – has bred her for genteel society but not for reading or writing or earning a living and she dreams of chucking everything up and going back to the India of servants and hill stations and colonial privilege that she knew as a young woman. Often unable to cope, the household – mother, son, and nurse – are periodically taken in hand with iron-willed capability by her rather grand and autocratic mother-in-law, whom she loathes above all others. This is the small, matriarchal society that made Kennedy and to which he says he owes so much.

As with A Boy at the Hogarth Press there is little retrospective, adult analysis of the experiences Kennedy recounts: his perspective is that of the very young boy he was at the time. But despite what the bare account above may suggest, this is not an especially grim or unhappy memoir. Indeed, Kennedy seems remarkably little affected by these childhood experiences, his response largely resigned or fatalistic.

There is a very brief postscript in which Kennedy explains that he went on to have a long career in children’s book illustration. What I think must be added to this, however, because Kennedy himself seems completely oblivious to it, is that he was saved by his upper class family background. For his education was neglected, he was admitted to Marlborough school only by dint of recommendations from titled family friends, but was subsequently dismissed because he couldn’t keep up with the work; his childhood seems to have left him both poorly socialised and desperate for real friends (this is perhaps even more evident in A Boy at the Hogarth Press); and at various critical junctures he seems to have been almost pathologically incapable – Leonard Woolf, for instance, admittedly an irascible and obnoxious man, said he was the most idiotic boy he had ever met. And yet despite this, he succeeds, emerging as a modest, often bewildered but likeable character whom one can’t help feeling considerable sympathy for. It also helps that he is devoid of self-pity and is as (gently) unsparing of himself as he is of those around him.

I think A Boy at the Hogarth Press is a lovely book, but read in conjunction with A Parcel of Time I think both memoirs become deeper and more remarkable works – very much a product of their time, and testament to a long-vanished world. It’s a real pleasure to have both of them, along with their wonderful illustrations, in a single, carefully produced volume. Highly recommended.

Alun Severn

December 2024