Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 30 Oct 2024

posted on 30 Oct 2024

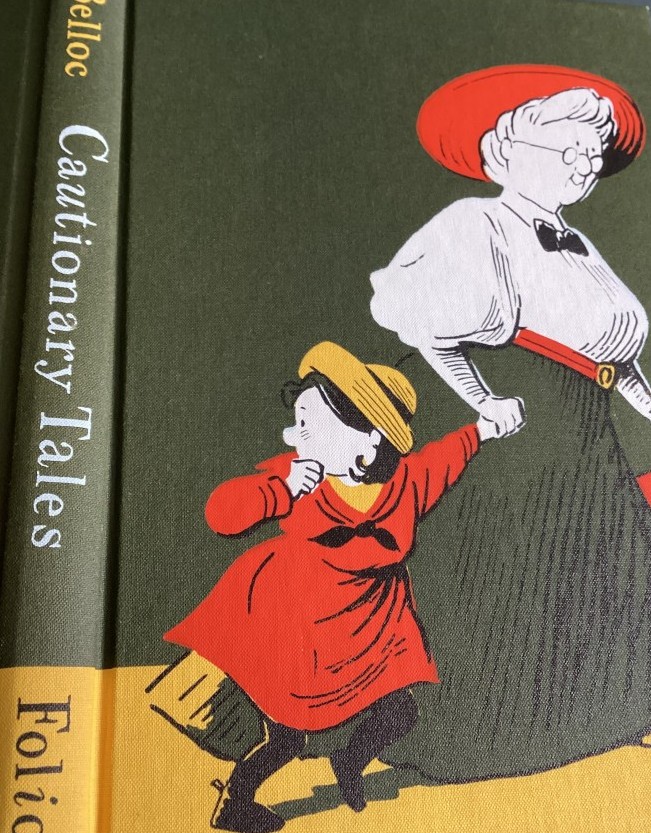

Hilaire Belloc’s Cautionary Tales for Children - that aren’t for children

Hilaire Belloc (1870 – 1953) was a French-English dual national who was by turns a writer, politician, critic, soldier and poet. He was also a committed Catholic who counted fellow Catholic, G.K. Chesterton as one of his closest friends. But he was also infamous in his time for being disputatious and revelling in a series of long-term feuds – especial with H.G. Wells.

Knowing this and looking at photographs of the man, you’d be forgiven for thinking that he was a forbidding and austere type but that would be to overlook his very well-developed sense of humour – sardonic and waspish - that is captured perfectly in the collection of poems he called Cautionary Tales for Children. It certainly won’t take you long to see that these are an entertainment for the more sophisticated adult rather than the innocent or naïve child of Victorian or Edwardian heritage.

Writing for The New Yorker in 2017, Calvin Tomkins said – accurately if somewhat unkindly:

“Belloc had the bad luck to mistake himself for a serious writer….he published more than a hundred and forty books and pamphlets….almost none of which are in print today.”

But the exception is Cautionary Tales, originally published in 1907, and never out of print since then.

Despite the poet’s own claim that these verses are “designed for the admonition of children between the ages of eight and fourteen years”, they are clearly aimed primarily at adults. Belloc is satirising the Victorian penchant for sickly moralising didactic verses that were indeed meant for the instruction of children that were designed to help guide their social and moral development. Here though, the children come to sticky ends, not in ways that make us think more carefully about our behaviour but in ways that make us laugh out loud.

So, Jim (Who ran away from his Nurse and was eaten by a Lion) slips his carer and :

“He hadn’t gone a yard when – Bang!

With open jaws, a Lion sprang.

And hungrily began to eat

The Boy: beginning at his feet.”

Or Matilda (Who told Lies, and was Burned to Death) unadvisedly apes the actions of the boy-who-cried-wolf and thinks that pretending the house is on fire and calling out the fire brigade is a jolly wheeze. Soon she finds that when reality intervenes no-one is listening any more:

“For every time She shouted ‘Fire!’

They only answered ‘Little Liar!’

And therefore when her Aunt returned

Matilda and the House, were Burned.”

And there are another half a dozen Tales all of which, bar one, describe a fatal disaster for an errant child – even if their transgression seems as modest as a constant desire to chew string.

The one exception to all this is the final eighth Tale: Charles Augustus Fortesque (Who always Did what was Right, and so accumulated an Immense Fortune). Belloc seems to be telling the story of how a child that does all the things expected of him deserves the fortune he accrues but that surface reading isn’t where this verse really takes us – it’s pretty obvious that Belloc’s subtext here is that society rewards the dull and unadventurous types and punishes anyone with a spark of non-conformist life in them.

What you’ll also notice is that the adults – usually the parents of the children haplessly slaughtered – all take the news of the tragedy with remarkable insouciance and take a sort of ‘o well such is life’ approach to their offspring’s demise.

I want to give the last words to Calvin Tomkins:

“His light verse, which was often compared favourably to that of Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear, may have seemed like hack-work to him….For a man of his mixed background and unique gifts, however, light verse proved a perfect outlet.”

The copy I read and which is pictured here is the one published by The Folio Society and is illustrated by the brilliant Posy Simmonds. Copies of this can still be found for under £20 on the second-hand market but you’ll find paperbacks at much cheaper prices.

Terry Potter

October 2024