Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 25 Sep 2024

posted on 25 Sep 2024

The happy accidents of reading: Richard Ford, Saul Bellow, Martin Amis

I love the happy accidents that sometimes come with reading and rereading. Recently, in something of a rough patch of reading when nothing seemed quite right or quite good enough I found myself turning to a novel I had long resisted: Richard Ford’s Canada, an immense novel about the hapless parents of Dell and Berner Parsons, fifteen-year old twins whose lives are about to be turned upside down by their parents’ bizarre decision to rob a bank so that their father can pay-off the small-time criminals he has become involved with. The reviews when it came out were extraordinary – John Banville going as far as to call it ‘the first great novel of the new century’. But I thought it written in excruciating detail, its prose flat and uninspired and despite its immense labour could find no spark of life in it. (It kept making me think of Ian McEwan’s most recent novel, Lessons, which similarly is imagined in minute, obsessive detail and yet remains stubbornly lifeless.)

And then I reread Saul Bellow’s final novel, Ravelstein. When this came out in 2000 Bellow was eighty-five and the reviews as I recall them were not all that much more than respectfully grateful that after a series of late-career novellas Bellow had at last produced a full-length fiction, a novel that must surely be his last, and that even if perhaps it wasn’t quite up to the glories of his earlier work, we must nonetheless be thankful for this late flowering. And I seem to remember that when I first read it, that was pretty much how I felt.

Rereading it I found it powerfully moving, funny and written in Bellow’s characteristically marvellous and hotly alive prose in which one seems to hear not just a mind at work, but a furiously intelligent mind running at full throttle on some of the highest-octane fuel. The narrator, Chick (a Bellow surrogate), has been asked by his oldest and dearest friend, Abe Ravelstein, to write a memoir of him after his death. Ravelstein is a conservative professor of political philosophy made unexpectedly wealthy from the sales of his surprise populist bestseller. Ravelstein is Chick’s hesitant, prevaricating, sometimes exultant, sometimes desperate rumination on how he can possibly begin to convey the combative, lifelong affection and mutual dependence the two very different men shared. How, where, does one begin?

What I didn’t know and had no recollection of even attempting to check when it was first published, is that the novel is a sort of roman-à-clef: it really is about a political philosopher, Bellow’s great friend Allan Bloom, who taught at the University of Chicago amongst other places, and who wrote the hugely influential bestseller, The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education has Failed Democracy (1987).

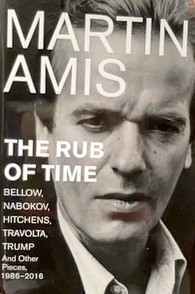

After two such differing novels I wanted to read some non-fiction and I turned to a book that I had had no intention of reading and didn’t even have a copy of: Martin Amis’s final collection of essays and journalism, The Rub of Time. I happened to hear pieces from it being read on Radio 4 recently by Bill Nighy, in that lovely, slightly louche voice of his, and realised that I was stupidly missing out on what could be a real treat.

The first of Amis’s essays considers Bellow, Updike and Philip Roth, amongst others, and for the first time in decades I found myself again thrilled by Amis writing in characteristically incisive, sometimes incendiary language about stuff he cared about deeply – the creation of fiction and the quality of literary prose. He examines why the Great American Novel once loomed so large in the cultural landscape and came to be dominated by Jewish-American writers. It was, he says, ‘because there was something uniquely riveting about the conflict between the Jewish sensibility and the temptations – the inevitabilities – of materialist America’. Here were novelists who ‘brought a new intensity to the act of authorial commitment, offering up the self entire, holding nothing back’. Of Bellow, whom he revered, he says, ‘Compared to him, the rest of us are only fitfully sentient…’

Elsewhere in the same piece he writes at some length about Nabokov, explaining that every five or six years he tried to read Nabokov’s longest novel Ada, until finally he admits to himself: ‘But this is dead.’ And it is here that he begins to articulate a series of ideas that made me sit bolt upright. He explains that he finally realised that whatever mysterious ‘life-giving power’ it is that produces the spark of life in the greatest fiction – its ‘radiance’ – had in Nabokov’s case faded. It is what happens, Amis says, to writers who ‘overstep the biblical span’. ‘Literary talent has several ways of dying’ he says but often there is a common symptom: writers ‘turn away…and fold in on themselves’ and they display ‘a decisive loss of love for the reader – a loss of comity, of courtesy’.

Who would have thought it would be Martin Amis, once considered the transgressive enfant terrible of British fiction and latterly a notorious curmudgeon, who would recognise that our continuing enjoyment of and respect for a writer depends on some scarcely describable sense of reciprocity, even of love?

For once this reciprocity – this comity, this shared sense of courtesy and cordiality – has gone, Amis explains, writers are at risk of producing ‘bursters’ – ‘what homicide detectives call…a waterlogged corpse at the stage of maximal bloat’. Who but Martin Amis would express this quite so accurately and with such inimitable vigour and relish?

So now, unexpectedly I have a new perspective on what was wrong with McEwan’s Lessons and Ford’s Canada and many other books I have tried but failed to read: an absence of comity; a turning away; a decisive loss of love. Bursters.

The happy accidents of reading.

Alun Severn

September 2024