Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Sep 2024

posted on 19 Sep 2024

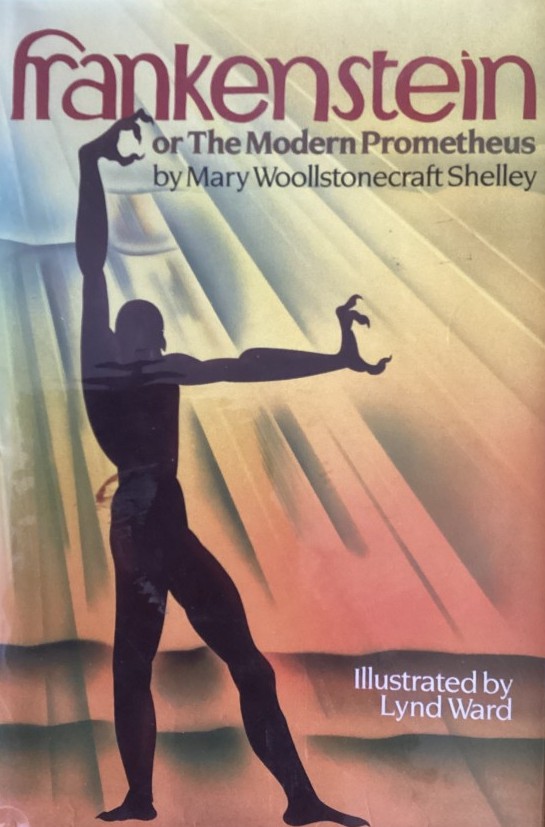

Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley

There are lots of reasons why this book is difficult to review and all of them serve to obscure the actual story that Mary Shelley set down, initially in 1816, and published in 1818. Probably the most difficult of the problems that any review needs to confront is that almost everyone thinks they know the story of Frankenstein already – it’s about the crazy scientist who creates a ‘monster’ from human corpses and brings it to life with huge bolts of electric, isn’t it? Well, that’s a reasonable summary of the movie (originally created by James Whale and later perpetuated by Hammer Horror) but it only has a touching relationship to the book.

The story of the book’s creation also casts a huge shadow – it might well be that the story of how Frankenstein came to be written is better known than the actual text of the book itself. In very simplified form that story goes something like this: Mary and Percy Shelley spent 1815 touring Europe, during which time they came across a Castle Frankenstein in Germany which had been the home of an alchemist notorious for his alchemical experiments. In 1816 they joined their friends, Lord Byron and John Polidori in a villa on Lake Geneva where they saw out some of the so-called ‘year without a summer’ (caused by the gigantic eruption of Mount Tambora) by engaging in a ‘writing competition’ to see who could come up with the most frightening Gothic horror story they could imagine. At the age of just 18, Mary Shelley is credited with coming up with the best of their efforts – Frankenstein, or the Modern Promethius – although, rather belatedly, the lesser known Polidori deserves more credit for his attempt, The Vampyr, which, it could be argued, has been just as influential in its own way.

Having got past these two big obstacles, what about the book itself? Well, frankly, that’s the next big problem because it’s something of a monster in its own right. Some part epistolatory novel, some part travel and exploration journal, some part Gothic horror and some part philosophical treatise on the nature of humanity and the ‘natural man’.

The book starts with a series of letters written by Captain Walton to his sister as he leads an expedition to the North Pole amid dangerous pack-ice. He tells of their perils and then their amazement at catching sight, first of a huge figure travelling by sled on the distant ice and then, even more surprising, the discovery of an emaciated character on an ice-flow who turns out to be Victor Frankenstein.

They take him on board and, as he slowly recovers, he tells the story of how he got there. And it’s an amazing story of how a young man becomes obsessed with his studies in chemistry at university and believes he’s found the key to how life can be imparted to what seems to be dead. Frankenstein says he won’t disclose that secret but he admits that he was able to apply his knowledge to the creation of a new life – a man he creates to be beautiful and perfect but which when he looks into the creature’s eyes turns out to be anything but. Repelled by what he’s done, Frankenstein runs from his house in panic – only returning later to find his creation has gone.

Over time, he tries, with the help of his close friend, Clerval, to put the whole episode from his mind and seems to be succeeding until he gets a letter from his father telling him his younger brother, William has been murdered. Frankenstein knows intuitively that his ‘Creature’ is responsible and to add salt to the wounds, a much-loved servant of the house, Justine, is accused of the deed and hanged for it. Frankenstein’s sense of guilt and moral responsibility sends him off to the solitary pursuit of mountain climbing in the Alps where he is finally confronted by his Creature.

What then follows is the story of what happened to Frankenstein’s creation after the scientist abandoned his house in terror. The Creature’s story allows Shelley to dip deeply into questions of moral philosophy – about how character is formed, how society responds to those who are ‘different’, how good can turn bad when individuals are treated inhumanly and the roots of emotions like rage and revenge.

Under threats of further violence to his family from the Creature, Frankenstein concedes that he is honour bound to create a female companion for him to alleviate his sense of isolation. The Creature promises that if this is done, he and his companion will disappear to the jungles of South America and never be seen again.

Although he agrees initially, Frankenstein can’t square the moral conundrum of acting as God and reneges on the deal, leading the Creature into another murder – this time of Frankenstein’s beloved, Elizabeth. Seeking revenge, Frankenstein pursues his creation across continents, ending up in the Arctic where he is discovered by Walton’s ship.

The book ends with the resumption of Walton’s letters telling of how when Frankenstein dies on-board, he discovers the Creature has sneaked onto the ship and is there at his creator’s bedside. He tells Walton that his sense of shame and desperation are so deep that he plans to commit suicide so that no-one but them will ever know the truth of the story – and he disappears across the ice.

By any measure this is an extraordinarily sophisticated piece of writing but it’s also not what most people will be expecting to encounter from a classic ‘horror’ story – which, sadly, is how this book is nearly always promoted.

I suggest you read it for yourself and discover what’s really there. Yes, it’s a bit of a rag-bag and no, there’s no mad scientist and no bolts of electricity being shot through corpses sown together and put on a table but what there is, is lots of speculation on the nature of life and humanity.

You won’t find it hard to get cheap paperback copies but there are some lovely illustrated editions to explore too – the one I read has illustrations by the great Lynd Ward which you can have a look at here.

Terry Potter

September 2024