Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 04 Sep 2024

posted on 04 Sep 2024

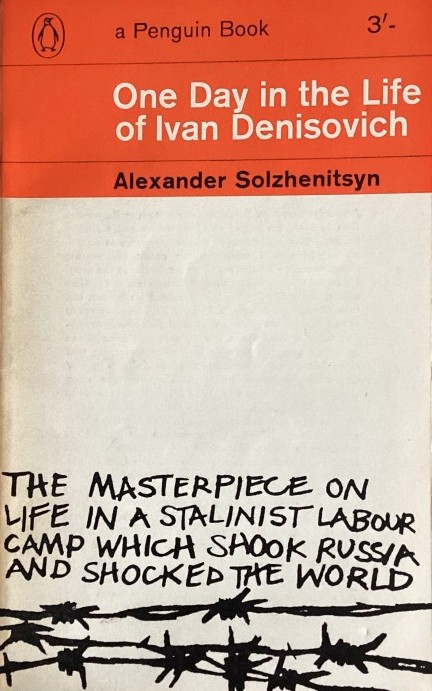

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

Back in the early 1970s, reading One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was a landmark in my development as a reader. It was the first book I’d read in a single sitting – reading my Penguin copy well into the night – and the first I’d felt so completely immersed in. I didn’t really know too much about the political background to the book but Solzhenitsyn and Soviet dissident writers were getting plenty of coverage at that time and it clearly influenced my decision to read it.

I went on to read plenty more of Solzhenitsyn’s work – Cancer Ward became a special favourite and I found myself being convinced that I had cancer of the leg (from this distance I’m not really sure what symptoms convinced me that I had the illness – but that’s the power of a good book for you). But it’s been a hell of a long time since I last reread Ivan Denisovich and it felt like a good time to revisit it.

Originally published in 1962 in the literary magazine, Novy Mir, when Khruschev was liberalising the Soviet Union’s censorship laws, the book caused a sensation. But, of course, when the tide turned against this openness, Ivan Denisovich was ruthlessly repressed – in common with just about everything Solzhenitsyn subsequently wrote. It was eventually published in the UK in 1964 – in hardback by Gollancz and paperback (the edition pictured) by Penguin.

The book is, literally, as the title tells you, one day in the prison life of Ivan Denisovich Shukhov who has found himself a victim of Stalinist paranoia and imprisoned with hard labour as a suspected spy – he’s in this position because during the war he’d spent time as a German captive. So, he’s got ten years to survive in a Gulag camp in the most terrible conditions where cold is a constant physical enemy and must be endured unless the thermometer drops below -41 degrees Fahrenheit.

The reader experiences Ivan Denisovich’s day with him, from the moment he wakes up feeling cold and unwell, right through to the end of the day when he assesses the small victories and minor setbacks. He’s a well-respected member of Gang 104 and, in common with the others in the team, feels grateful to have Tyurin as his gang foreman – someone who is as hard as nails but scrupulously fair to his men. We accompany him as he goes out to work in the brutal cold where the mortar for laying bricks freezes before it can be laid and sit down with him to eat the nauseating fishy slop they are served up.

Little victories are everything here and food has power. Ivan Denisovich finds ways of squirrelling away crusts of bread to barter with and he cultivates relationships – especially with Tsezar who gets food packages from outside and gets rewarded for doing all manner of small jobs for him.

There is no world outside the camp for Ivan Denisovich. It’s a profoundly political book with virtually no explicit politics and we get to see how notions of dignity and humanity get redefined in these situations. People will do whatever it takes to survive but Ivan Denisovich shows how, in such circumstances, doing the right thing and thinking of others as human beings reaps its rewards.

I was delighted to discover that as soon as I opened the book I re-entered the world Solzhenitsyn created with a renewed respect for the achievement of transporting me to this God-forsaken prison camp in the sub-Arctic Gulag.

If you haven’t read this book, it’s a must because its not a historical record but a living testament to the human urge to survive. Paperback copies are not hard to find and won’t break the bank.

Terry Potter

August 2024