Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 26 Aug 2024

posted on 26 Aug 2024

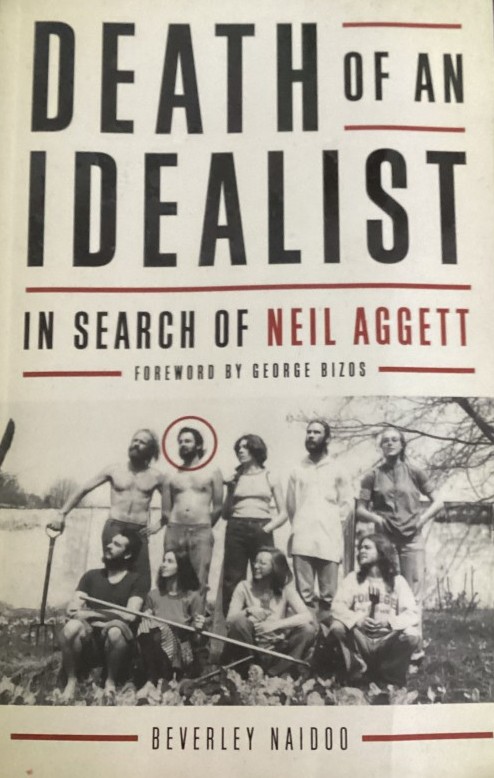

Death of an Idealist: In Search of Neil Aggett by Beverley Naidoo

In July of this year, I read and reviewed A Dry White Season, Andre Brink’s excoriating condemnation of the way the South African Apartheid state and its secret police terrorised and silenced any opposition to it. I was subsequently delighted to find that the wonderful novelist, Beverley Naidoo had read the review and found much in it to agree with – especially the idea that the tactics and methods used by the Apartheid police were a universal template used by repressive regimes everywhere. Not only that, she was also kind enough to send me a copy of her extraordinary examination of the workings of the repressive Apartheid regime, Death of an Idealist: In Search of Neil Aggett – a study that (undeservedly) often receives less attention than her young adult fiction.

Naidoo isn’t just a top-rate writer, she’s an activist who has never stopped campaigning for social justice. Exiled from her native South Africa as far back as the 1960’s, her books have brought the realities of Apartheid to younger readers in the most accessible and vivid ways – her breakthrough first publication, Journey to Jo’burg is now approaching its 40th anniversary and she has also collaborated with some great illustrators on a range of diverse picture books.

But Death of an Idealist is something else again. This forensic study of State oppression is clearly personal – not just because she was a victim of their operations but because it involved so many of her friends and family. Neil Aggett, just 28 and the first White detainee to die under arrest in a police cell, was Naidoo’s second cousin – something which gives the book an extra edge.

The book is massive – both literally (almost 500 pages) and metaphorically (in terms of the issues it explores). It’s possible to think of this book as having three main sub-divisions: in the first we get a portrait of Aggett the man, the second gives us the unvarnished truth of his arrest and death and, finally, a third part looks at the bigger political consequences and lessons that flow from the tragic killing.

I found the portrait of the younger Aggett enormously sympathetic – it felt as if it could have been the journey many of us make as we develop a political awareness and a sense of social mission. Leaving behind a conservative (even reactionary) family home, going to university, encountering injustice, seeking explanations for that injustice and finding a home in the trade union movement might be my story too – except I didn’t have to take that journey in the monstrous circumstances of Apartheid.

The story of his arrest and eventual ‘suicide’ and the treatment he received is presented in all its distressing detail. There’s no turning your eyes away from the brutal physical and mental torture or from the dehumanising sense of entitlement and impunity that the police clearly felt they had. In his foreword to the book, George Bizos, Senior Counsel, Johannesburg Bar puts it this way:

“The evidence brought to light during the inquest demonstrated the flagrant disregard for human dignity that existed in South Africa.”

The consequences of Neil Aggett’s death still echo through the corridors of those States who turn to covert violence to quell dissent. Neil’s funeral brought huge numbers of people – Black and White – onto the streets and subsequent inquiries along with the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission have helped to lay bare not just what really happened to a 28-year-old White man but to countless numbers of other, unnamed or unknown victims.

What Beverley Naidoo has set out for us in painstaking detail is how the tyrant functions and what that means in terms of brutalising whole communities. These atrocities aren’t confined to one rogue state at a particular time in history – they are with us now and there are likely to be more stories similar to Neil Aggett’s happening around the world – in Russia, Israel, Palestine, Sudan and so many more.

It is books like this that challenge the idea that this will continue unchecked – but only if more people read them. Copies of the book are available online but quite hard to find and not cheap – but it is essential.

Terry Potter

August 2024