Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 29 Jul 2024

posted on 29 Jul 2024

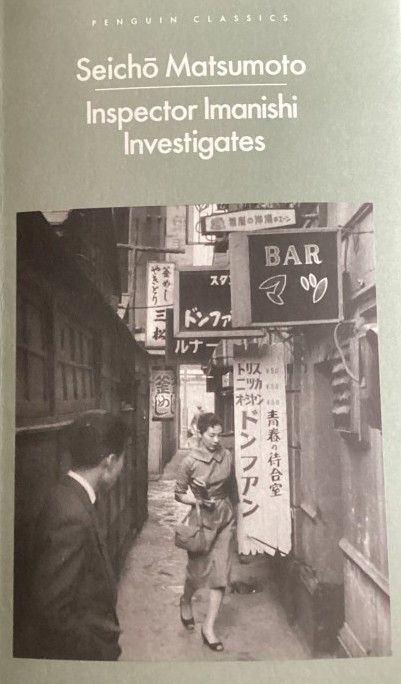

Inspector Imanishi Investigates by Seichō Matsumoto

Seichō Matsumoto (1909 – 1992) is generally seen as the writer who popularised the detective fiction form in Japan – and his output was prolific and popular. But for those of you accustomed either to the Golden Age detective authors like Agatha Christie or to the more modern and gritty style of the modern ‘damaged’ detectives you’ll find in the books of writers like Ian Rankin, Matsumoto’s approach may come as something of a surprise.

I’m used to detective stories being heavily action and plot driven – to be page-turners that gallop along. But you won’t find that here. This book has a complex plot, yes, but it requires a certain slowness of reading as Inspector Imanishi edges his way through the mystery in a dogged and dedicated fashion.

It’s impossible not to get the sense of having entered an entirely different cultural milieu; this is Sixties Japan on the cusp of its engagement with emerging Western mores but still with its very different social and professional codes. So, Imanishi isn’t a rebel – quite the opposite, he reports regularly to his superiors and worries constantly about overspending his travel budget to no gain. He’s not a drinker – modest afterwork drinks of Saki with a police colleague and friend is all he manages. He’s happily married to a wife that seems to understand him and his dedication to the job.

One morning a man is found viciously battered to death on a local railway line. It seems that the only clue Inspector Imanishi has to what happened is the fact that the victim had previously been seen talking to another man who had a distinctive regional Japanese accent. This modest clue sends the Inspector on lengthy trips across the country trying to find out who the dead man is and who might have been responsible for his murder.

When it transpires that the dead man was an ex-policeman who has an almost saintly past, the mystery deepens. While on his travels Imanishi and his closest associate, the younger policeman, Yoshimura, encounter a group of radical, avant-garde, emerging young artists known as the Nouveau Group and they find themselves slowly becoming more and more entwined in their story.

I’m not even going to try and summarise any more of the plot because over the 350 pages of the book, the steady accretion of information Imanishi uncovers is full of red herrings, cul-de-sacs and moments of breakthrough that would defy explanation without this review becoming overly long and being filled with spoilers.

Matsumoto is clearly not just interested in producing a devilishly complex murder investigation here – there’s obviously an attempt to talk about the emerging Japan and its engagement with the West and especially Western ideas. The Inspector is in many ways a traditionalist – he writes and loves Haiku – but Matsumoto brings him into contact with new ideas and there’s a strong strand of psychological investigation here when it comes to the motive behind the murder. And, while I wouldn’t claim that the author is pushing feminist ideas here, there’s clearly a questioning of some of the cultural assumptions around the role of women and how they are seen in Japanese society.

I’m willing to bet that you will either be, like me, seduced by Matsumoto’s approach and find yourself dragged into Inspector Imanishi’s world or you will be puzzled and a bit irritated by why the plot doesn’t just get going a bit faster and push forward with more vigour.

Try it for yourself and see what you think. It’s been reissued in a very nice Penguin with a beautifully designed card cover that, very usefully, includes maps of Japan in the front few pages that makes you appreciate the scope of the Inspector’s travels.

Terry Potter

July 2024