Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Jul 2024

posted on 08 Jul 2024

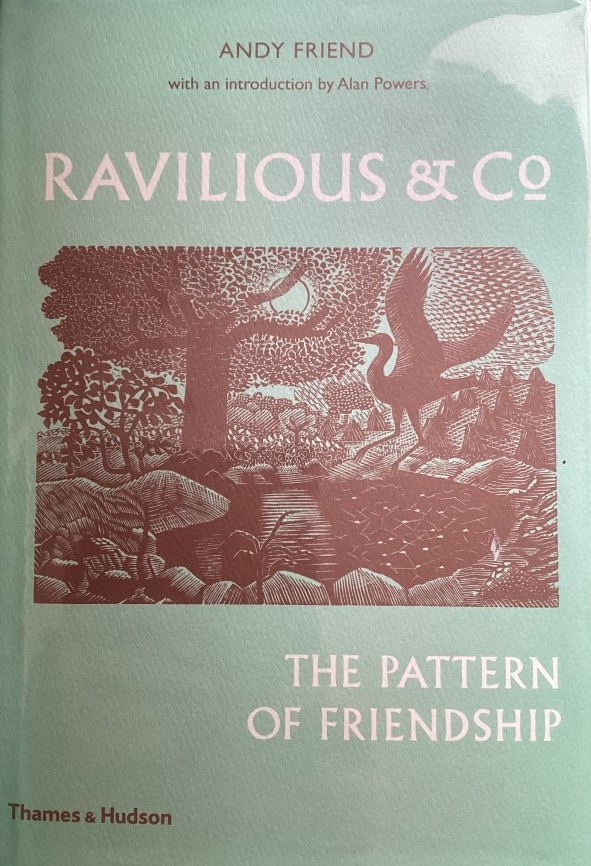

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship by Andy Friend

For some years now I have been obsessed with the artist-designer Eric Ravilious (see here, here and here). With Ravilious, one gets the whole package, as it were – an iconic watercolourist, a superb book illustrator, a wonderful engraver and lithographer, a tasteful designer able to work in almost any medium and perhaps most importantly an acclaimed war artist who lost his life when the spotter plane he was in disappeared over Iceland. He was just thirty-nine.

There are many excellent books that showcase various aspects of Ravilious’s work but recently, wanting to know more about the man himself and the circle he moved in, I turned to Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship by Andy Friend (2022).

It is hard to believe now that there was a time when Ravilious, along with many of his contemporaries – his wife and fellow artist, Tirzah Garwood, Helen Binyon, Edward Bawden, Barnett Freedman, and Enid Marx, to name only the better known – were considered marginal. Because they had all graduated from the Royal College of Art during a period when it was most closely identified with design and commercial art some critics felt they were not the equal of proper ‘fine’ artists.

Where Friend’s book truly shines, I think, is in the insights he offers into the relationship between the various types of work produced by the group. Thanks to his exhaustive research and the superbly reproduced images, there may currently be no better book revealing the interconnectedness of their work.

What I found less satisfactory – but this is almost certainly a problem of mine rather than a failing of the book – is the sometimes unremitting focus on the group’s personal relationships and love affairs. Instead of finding them to be the largely self-effacing, modest, hard-working disciplinarians I so wanted them to be, the impression one gets is of a rather bohemian, somewhat promiscuous group, most of whom had a capacity for selfishness. Another notable characteristic, but one which would perhaps warrant further exploration, is that while the men in Ravilious’s circle (himself included) were predominantly working class, the women, albeit not exclusively, tended to be from higher up the social scale (perhaps reflective of the intake of the ‘design-centred’ RCA at that time). Indeed, Tirzah Garwood confessed that prior to marrying Ravilious she felt intimidated by his ‘rather frightening working-class world’. (But then both she and her wealthy military family were frightfully posh.)

I thought that these final war years made unbearably sad reading. While Ravilious and Tirzah both had other lovers there is no doubting the bedrock of love and affection that bound them together, despite their often acute unhappiness. Nor is there any doubt regarding the love they shared for their three children – although at first Ravilious was not always an exemplary father. But during the years that Ravilious served as a war artist Tirzah suffered immensely – childhood illnesses, primitive rural accommodation, wartime privation and repeated surgery for breast cancer all taking a dreadful toll. The two older children were still both under eight and Anne barely a year old when Ravilious was killed. Tirzah remarried in 1946 and the years she had with her new husband were by all accounts deeply happy ones, even when it became evident that the returning cancer was in fact terminal and she died in 1951 aged just forty-two.

There is a sense – and perhaps a hint that Ravilious felt this too – that the war brought things full circle. The brothers Paul and John Nash, for instance, who were a generation older than Ravilious and in Paul’s case had at various times taught many of the RCA students, both served as war artists during both wars; so too did Sir William Rothenstein, who was principal of the RCA for fifteen years. He died in 1945 aged seventy-three, his war service perhaps contributing to declining health. His son noted, ‘What a strange conjunction there was of two remote periods of time when this small figure, mentioned in the “Goncourt Journals”, the familiar of Verlaine, Pater and Oscar Wilde, was out over the North Sea in a Sunderland flying boat.’ And while Ravilious served in Norway, the North Atlantic and Iceland, where he would meet his death, Bawden served in France and the Middle East, but survived the war and died in 1989 aged eighty-six.

The war would also close another circle. In 1928 Rothenstein was instrumental in Ravilious and Bawden securing their first joint commission when a wealthy American art collector agreed to fund the painting of uplifting murals on the walls of the refectory of the Morley College for Working Men and Women in central London. This was a job which would take them almost two years, the murals finally being unveiled by Stanley Baldwin in 1930. During the Blitz the college provided temporary shelter for people from various bombed-out parts of the city and on the night of the 15th October 1940 there were almost two hundred people there when a 2,000-pound bomb hit the building. Fifty-seven were killed and the last bodies – ‘Mrs Roberts and little Ellen Harman’ – were eventually found in the rubble three weeks after the raid took place.

I finished The Pattern of Friendship with a fundamentally different understanding of Ravilious and his circle and of the interconnectedness of their work. Deeply evocative and exhaustively researched, it is an extraordinary and tragic story. It is only currently available in hardback but it benefits from Thames & Hudson’s exemplary production values and there seem to be secondhand copies around for under £10.

Alun Severn

July 2024

Elsewhere on Letterpress:

High Street by Eric Ravilious and JM Richards

White Horses by Eric Ravilious and Anne Pattullo: recreating Eric Ravilious’s “lost Puffin”

The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars by Frances Spalding