Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 26 Jun 2024

posted on 26 Jun 2024

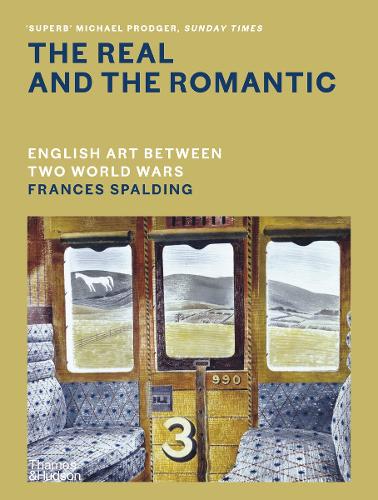

The Real and the Romantic: English Art Between Two World Wars by Frances Spalding

The Real and the Romantic, Frances Spalding’s huge survey of English art between the wars, is a beautifully produced and printed book with superb plates.

Spalding explores the changing trends in art between the wars, beginning with the vast outpouring of material documenting and memorialising the trauma of the First World War, much of this officially commissioned, produced by artists who were in some cases startlingly young and more or less at the beginnings of what would later become illustrious careers. Paul Nash, for instance, was not yet thirty when he produced his extraordinary avant-garde influenced paintings of the shattered landscapes of the Western Front in 1917 and 1918.

The volume of information and the level of detail Spalding employs is nothing short of staggering and her marshalling and control of this information is impressive. There were occasions, however, when I found myself wishing she would be more selective. But of course, if some aspect doesn’t interest you – the internecine battles between the various post-war committees commissioning war art and other memorials is a good example – you can always skip it.

Overall, however, I found Spalding’s broader narrative both convincing and compelling: the early influence of the avant-garde in painting during and immediately after the first war and the ‘pitiless realism’ this sometimes depicted; the gradual reawakening of an English pastoral tradition and the desire to capture the landscape as a ‘place of the mind’; the gradual discovery of art forms beyond the classical Western tradition and a gradual incorporation of these forms, especially in sculpture; the revival of classicism; a new objectivism and austerity as fears of a second, impending war grew. The more one reads, the more one recognises the enormity of the task Spalding is undertaking.

But in a book that is as much about the social, economic and cultural circumstances of the artists considered as it is the work they produced, I found Spalding’s breezy disregard of private wealth an irritant. For example, the artist Ben Nicholson, through his marriage to Winifred, also an artist and at times perhaps a more prominent one than her husband, was part of the Howard family (of Castle Howard), a family that had not one but two castles to its name. The couple lived for some years in Italy in a villa that Winifred’s mother bought for them but in later years moved to a Cumberland farmhouse that Winfred bought and had stripped of its Victorian ornamentation and austerely restored. An early collector of the couple’s work, Helen Sutherland, was a wealthy heiress whose buying trips to artists’ studios were by chauffeured Rolls-Royce. And yet Spalding doesn’t seem to regard these circumstances as informing the art the Nicholsons created. I found that curious, but perhaps a life spent studying art and artists inures one to the question of private wealth.

Anyway, along the way I became acquainted with artists who were entirely new to me, as well as fascinating side-stories in the evolution of art between the wars. I was transfixed, for instance, by Algernon Newton, who researched and eventually adopted the methods of the Old Masters, painting eerily placid and softly lit depictions of urban landscapes that transplant the glories of Canaletto’s Venice to the back streets of Paddington, Bayswater, Kentish Town and Camberwell – and most beautiful of all, the warehouses and factories of the Regent’s Canal. But Newton is just one example amongst countless others, every few pages producing equally interesting artists previously completely unknown to me.

The Real and the Romantic is the kind of book that offers countless hours of pleasure and is as much a joy to handle as it is to read. Currently only available in hardback but new and secondhand copies for under £20.00 seem widespread. Highly recommended.

Alun Severn

June 2024