Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 May 2024

posted on 05 May 2024

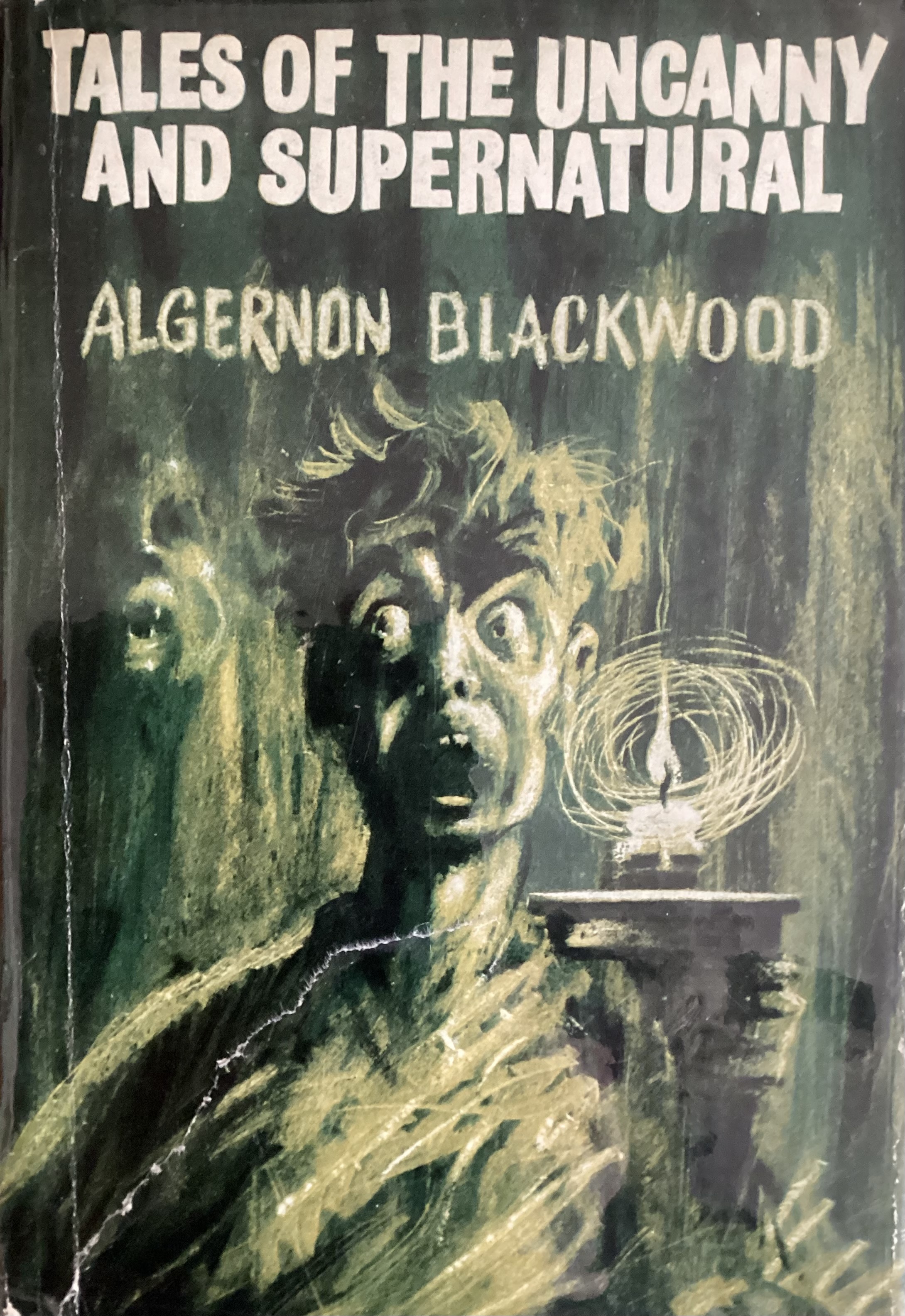

Tales of the Uncanny and Supernatural by Algernon Blackwood

The reputation of Algernon Blackwood (1869 – 1951) rests on his collections of supernatural or modestly spooky short stories that he published in various collections and periodicals. This particular collection is culled from these earlier publications – although, a touch irritatingly, some of his most feted stories aren’t included.

For aficionados of the uncanny tale, Blackwood’s name is often mentioned with admiration but I have to confess that I have never consciously read anything of his before – although there’s a good chance I might have come across one or two in the past when I’ve picked up a treasury of assorted short tales of the supernatural or some such publication. So, in a way, I came to this without too many expectations or presumptions.

A key theme of Blackwood’s soon emerges from this collection – the ambivalent and semi-mystical relationship between humanity and nature. Running Wolf, for example, sees an individual on an isolated fishing trip encounter a mysterious timber wolf that turns out to be the embodiment of the restless spirit of a native Canadian Indian seeking his rest. And, in a story that feels almost more like a novella, The Man Whom the Trees Loved, explores the, often antagonistic, relationship between nature mysticism – a kind of Pantheism – and Christianity. Writing for The Guardian in 2007, Kate Mosse put it this way:

“He understood the power of the intangible, and developed a style of writing that relied on suggestion and atmosphere. Regarding all experience as - potentially - spiritual, he believed that an understanding of nature would lead to faith and a knowledge of how to live. In the years leading up to the first world war, he produced an extra-ordinary and diverse body of occult tales: innocent campers who pitch their tent in a place where another dimension intersects with our own ("The Wendigo"); the psychological transformation of a fey aristocrat ("The Regeneration of Lord Ernie"); a house haunted by the echo of religious intolerance ("The Damned"); a man seduced by the forest ("The Man Whom the Trees Loved").”

I ended up liking the very first story in this collection the most. The Doll is probably the closest Blackwood comes to a ‘horror’ story and relies on some of the tried and tested cliches of the genre. Colonel Masters has return to his country home after service abroad in the army and now lives there with his (emotionally neglected) daughter, her nanny and various house staff. A mysterious package is delivered by a mystery man which contains a doll – that Masters insists must be thrown away. Instead, a well-meaning domestic gives it to the daughter – and from there a tale of terror emerges that will result in the death of the Colonel.

It's probably worth saying that this tale – and others – contain discriminatory language that is likely to put your teeth on edge but which was, of course, commonplace in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

But it wasn’t that out-dated language that made me feel that this collection represents more than enough of Blackwood for me. I found his prose to be often lifeless and hard-going and the underlying philosophies of what you might call ‘animism’ (the sentience of nature) a bit uncongenial.

I’m clearly out-of-step with many readers and the likes of novelist Kate Mosse who ranks him with Lovecraft, M.R. James and Le Fanu and says:

“ the most evocative of his descriptions belong in the company of the best and most reflective writers on landscape and nature.”

All I can say is that you’ll have to read him yourself and find out if you agree with me or with his admirers.

Terry Potter

May 2024