Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Apr 2024

posted on 08 Apr 2024

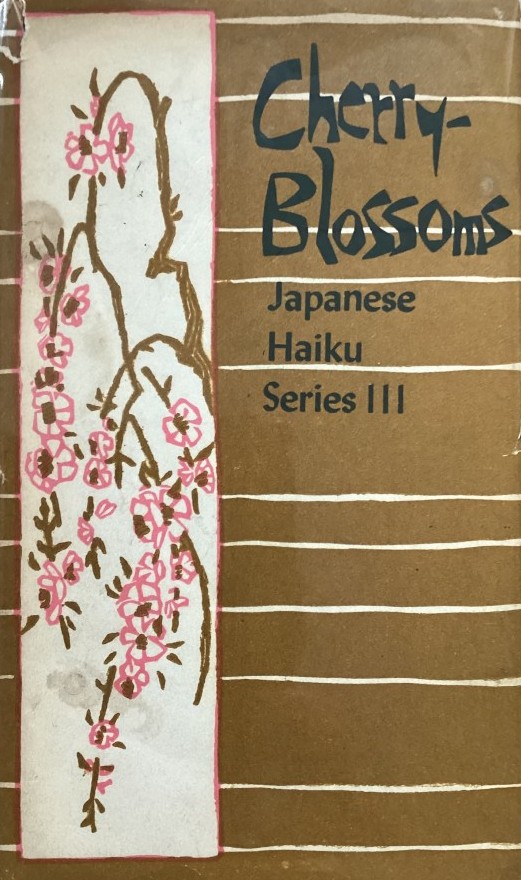

Cherry-Blossoms: Japanese Haiku (series III)

I read much less poetry than I used to. I’m not sure why that is but I find myself too distracted by other media and too addicted to story and prose narrative to have the patience to sit and take my time over poetry. At my worst I find poetry contrived and irritating but, when I’m in the right mood, I can believe that poetry, along with music, is the most sublime of the arts.

There are, however, some poets and some poetic forms that I do turn to and retain a deep-seated affection for. The Japanese verse form we know as the Haiku, is one of them. I first encountered the Haiku at university when one of my more inspiring lecturers introduced us to the poetry of the Imagists – a US/UK collective of poets including Ezra Pound, Hilda Doolittle (HD) and T.E. Hulme – who:

“wrote succinct verse of dry clarity and hard outline in which an exact visual image made a total poetic statement” (Britannica)

The Imagists took inspiration from the Japanese haiku form which provided a perfect template for their ideas of what verse should be. The haiku – unrhymed poems organised as 17 syllables in three lines of 5, 7, 5 – has its origins in 17th century Japanese literature but it didn’t become established as a form in its own right until the 19th century. Originally the 17 syllables acted as an introduction to a longer poem and would essentially be a mood and scene setter.

However, the early masters of the form – Bashō, Buson, Issa, Masaoka Shiki, Takahama Kyoshi and Kawahigashi Hekigotō – refined the haiku into a stand-alone artform. Initially, haikus would deal with nature, time and place but as it developed into the 19th century the scope of its subject matter expanded and it became a universally used structure for poetry across the world.

Although people commonly call any grouping of words into three lines of 17 syllables in a 5, 7, 5 formation a haiku, I still prefer the classical work of the early masters of the form whose intent was to offer observations of nature that reflect the inner state of the poet. This bond between nature and spirit isn’t made explicit but inferred by what the poet chooses to emphsise:

“High sun still burning

In the falcon’s eyes…. down to

My Earth-bound wrist.” (Taika)

I recently found the lovely 1960 collection shown here – Cherry Blossoms – published in a delicate and almost pocket-sized hardback by Peter Pauper Press, for next to nothing and it’s an absolute joy. Haikus by the classical Japanese greats of the form are set out under the four seasons and decorated on each page with a margin of woodcut decoration.

I can only find the odd one or two copies for sale on the internet and they come in at over £20 – unless you’re prepared to pay extra for a copy from the USA which would bump up the cost to over £30. But, if you want my opinion, it’s well worth it.

Terry Potter

April 2024