Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 10 Mar 2024

posted on 10 Mar 2024

Revisiting Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee

Laurie Lee’s Cider with Rosie has long been a favourite here at Letterpress and indeed was one of the first reviews posted. It has been on my ‘don’t forget to reread’ list for years.

But a curious thing happens with books that have achieved immense and enduring popularity: we become somewhat blind to them. I think this is even more the case when the book in question has been a set-text in schools for decades. Public perception of the book – and sometimes our own feelings towards it – also become blunted or inaccurate. For instance, when I think of Cider with Rosie my own ‘shorthand’ description is something along these lines: ‘Laurie Lee’s lyrical, romantic account of a rural childhood and loss of innocence in the 1920s’. As soon as I started to reread the novel I realised how lazy this description was, for it is considerably darker in tone than I remembered, and is a long way from the kind of hazy, golden nostalgia that many believe characterises the book.

It opens with Lee a bawling, apparently forsaken three-year old, plonked down from a passing farmer’s cart into uncut grass at the edge of a field. His fiercely loving but sometimes disorganised mother, deserted by her husband and left to raise the families of both his marriages, is uniting all eight children in the damp, cold sprawling cottage that is home. There is never enough money or food and hunger is a constant companion. The slaughter of the Great War is never far away; illness, madness and death are familiars. Living conditions are primitive and life in the remote Slad valley in Gloucestershire has hardly changed in centuries – a connection Lee feels viscerally:

‘It was something we just had time to inherit, to inherit and dimly know – the blood and beliefs of generations who had been in this valley since the Stone Age. That continuous contact has at last been broken, the deeper caves sealed off forever. But arriving, as I did, at the end of that age, I caught whiffs of something old as the glaciers. There were ghosts in the stones, in the trees, and the walls, and each field and hill had several. The elder people knew about these things and would refer to them in personal terms, and there were certain landmarks about the valley – tree clumps, corners in the woods – that bore separate, antique, half-muttered names that were certainly older than Christian.’

One of the things I most admire about Lee’s prose is its layered imagery, subtly weighted with underlying echoes and resonances that can be read at different levels. I’ll just give one example; others will have their own favourites. There is a profoundly sad section in which Lee talks of his mother’s final years. He fondly remembers the stories she would tell of her earlier romances – especially the boorish local suitors she turned away: ‘The postman she rejected because of his wig, the butcher who bled from her scorn, the cowman she’d shoved into Sheepscombe brook to cool his troublesome fires – there seemed many a man up and down the valleys whose love she once had blasted.’

The ‘rejected’ postman put me in mind of an incorrect address struck through with blue crayon; the butcher, bathed in blood every working day but still made to bleed further by her excoriating scorn; the cowman ‘shoved’ into the brook, like a herder nudging a recalcitrant cow in the right direction. It may be fanciful to read so much into the work but it is rich in these kind of allusions. One of its great pleasures is that it cannot be exhausted.

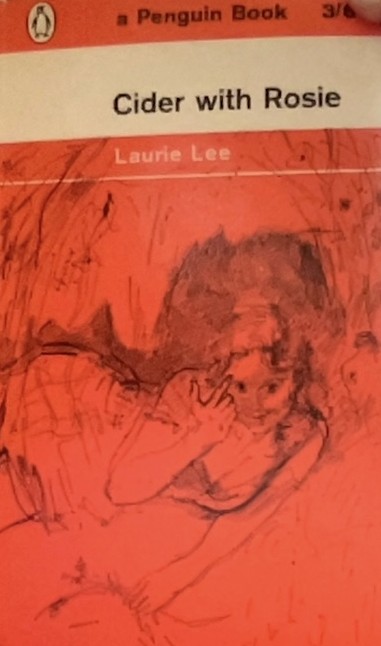

I have been reading Cider with Rosie slowly over the past ten days or so, rationing myself to a few pages at a time, relishing every word. Perhaps you too have a copy sitting neglected on your shelves, passed over repeatedly because it seems so familiar you doubt it has anything further to offer; or perhaps you once read it under duress at school, so many years ago now that you would prefer not to remember? Whatever the case, if it has been a long time since you last opened it, give it a try. It is unlikely to disappoint. Do try, however, to find an edition that does full justice to the magic of John Ward’s original line illustrations. Some versions omit these, or reduce them in size so that they are just incidental ornaments. Earlier Penguins and older hardback editions (including book club versions) tend to use them at full-page and they enrich the work immensely.

Alun Severn

March 2024

Laurie Lee elsewhere on Letterpress:

I’ve been thinking about why I love Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee

As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee

Village Christmas and Other Notes On The English Year by Laurie Lee