Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 17 Jan 2024

posted on 17 Jan 2024

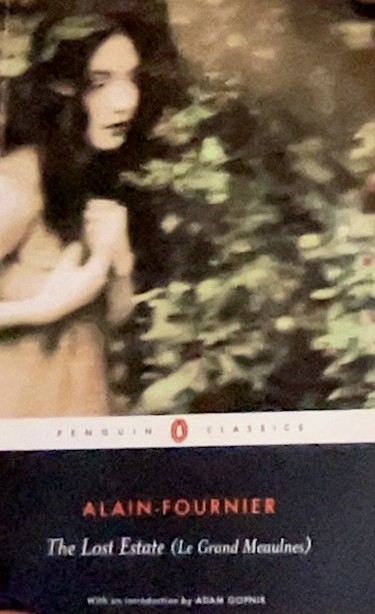

Le Grande Meaulnes by Alain-Fournier

Alain-Fournier’s novel of adolescent passion and yearning is both a hymn to youth and an elegy: it was published in 1913, when Alain-Fournier was just 26; the following year, he was killed in action in the Great War, fighting at Meuse in northeast France. He had been in the army just one month.

It is set in rural provincial France during the 1890s. The narrator is a young man called François Seurel, whose father is the headmaster of the village school. Early one winter, a new boy, a troublesome young man called Augustin Meaulnes comes to the village, sent by his parents to join the school as a boarder. Handsome, adventurous and wilful, he is almost two years older than Seurel and they strike up an instant friendship in which there is a strong element of hero-worship on Seurel’s part: an unspecified hip problem makes it difficult for him to walk far and he admires Meaulnes’ physical vigour and his devil-may-care attitude.

After a few months, Meaulnes is restless. Seurel’s grandparents are about to make their annual visit and Meaulnes is chosen to accompany Seurel to collect them from an inn a few miles away, using a borrowed horse carriage. But Meaulnes decides to combine the task of collecting the elderly couple with an adventure of his own and leaves early without Seurel. Three days pass and the horse is found wandering freely, the carriage empty. When Meaulnes eventually returns he is exhausted, ravenous and filthy and will tell no one where he has been.

Eventually he explains to Seurel that he became lost and by accident wandered into the grounds of an estate – an isolated estate surrounded by forest, with a grand but dilapidated house in which a raggle-taggle army of children appeared to be in charge of a strange fête. He meets a bewitching young woman, Yvonne de Galais and her dashing brother, Frantz, whose parents own the estate. As Seurel is bewitched by Meaulnes, so Meaulnes in turn is bewitched by Yvonne and falls immediately in love with her; he also sees in Frantz the sort of romantic hero that Seurel considers Meaulnes himself to be. There are numerous parallels of this kind in the book. The rest of the novel is the story of Meaulnes’ effort to rediscover the lost estate and the young woman who lives there.

As this brief outline of the story may suggest, there is more than a hint of melodrama about Le Grand Meaulnes; but there is also an indefinable but characteristically French romanticism too, and that is why I decided to read it again. I remembered loving the book when I first read it in an old Penguin Modern Classic edition in the early-70s. At that time, fantasy literature of all kinds was hugely popular and I seem to remember that Le Grand Meaulnes found readers amongst fans of Tolkien, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, C S Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia and Alan Garner’s increasingly demanding novels of myth and folklore, such as The Owl Service.

And it was in this spirit that I approached it again. I wondered whether it would live up to my memory of it; I also wondered whether it really did suffer from some of the imperfections I also vaguely remembered. It turned out to be even more flawed than I remembered but also much more affecting.

As far as the flaws are concerned, there is something disorganised about its narrative structure and I sometimes found myself losing patience with its inexplicable journeys and schoolboy pranks and sudden lurches into melodrama. I’m sure that these structural problems and occasional narrative confusions could have been sorted out, but one feels there was no time for this: Le Grand Meaulnes reads as if written in urgency and published at speed, almost as if its author knew that within a year he would be amongst the slaughtered millions of the First War.

But the more I read the more I also began to realise how profoundly I had misunderstood the book, for it isn’t really the story of an enchanted lost estate, a tatterdemalion paradise ruled by children. Nor is Augustin Meaulnes really its central character. No, the real heart of the book is the effect its events have on François Seurel, and what gives the book its curious, lasting power is the deceptively simple prose in which it is written – its descriptions of the daily routines of the rural school, the rhythm of the seasons and the wintry landscape. For all its fabulism, Le Grand Meaulnes is realist in its techniques and while it may be flawed, its poetic, gravely beautiful prose and the mounting sense of tragic loss that pervades it are beautifully realised in this translation.

Alun Severn

January 2024