Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 Nov 2023

posted on 09 Nov 2023

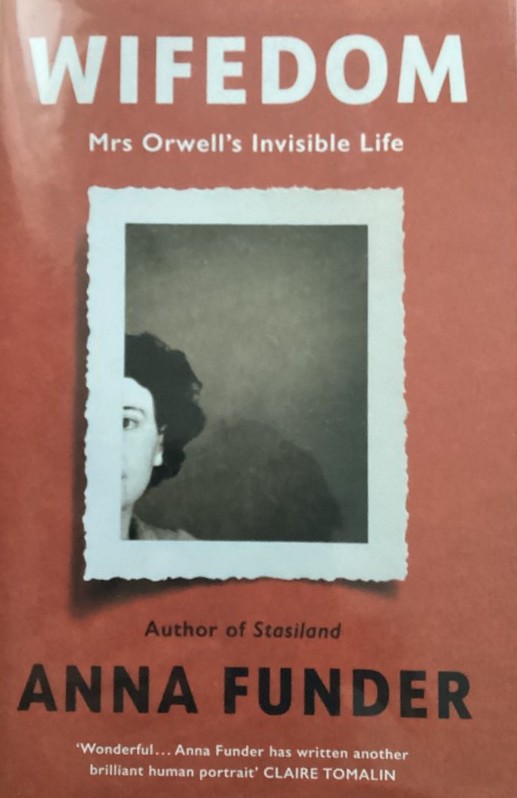

Wifedom by Anna Funder

Eileen Maud Blair (née O'Shaughnessy) married George Orwell in 1936 and the two lived together until 1945 when, at the age of just 39, Eileen died during an operation to perform a hysterectomy. In 2020 the first full biography of Eileen by Sylvia Topp was published and I think it’s fair to say it had a pretty lukewarm reception. Rachel Cooke’s review for The Guardian in 2020 captures the sort of critical response the book received:

“Does Eileen really deserve a full-length biography? The book’s subtitle, The Making of George Orwell, rather suggests that she doesn’t; that the single most interesting aspect of her life – at least to us, at such a distance from her – was the fact of her marriage. Aware of this, Topp tries hard to show that she had a greater influence on Orwell’s work than his male biographers have so far allowed. But her arguments are unconvincing.”

In many ways, Wifedom by Anna Funder feels like it takes on these criticisms and tries to fill in those perceived shortcomings in Topp’s thesis and give them a more rounded reality. Funder has a couple of weapons up her sleeve in this endeavour: firstly, she has access to half a dozen letters written by Eileen that have never before had public release; and, secondly, she’s happy to use a sort of directed fiction to fill in the gaps where the historical record is silent. There’s a secondary project here too – alongside the excavation of Eileen is a desire to use her story to illustrate just how a patriarchal literary world erases or airbrushes out of existence the women who occupy the same space as famous male authors. They are trapped, she would argue, in the state of ‘Wifedom’ that demands they keep a male world turning and remain anonymous.

Funder is also no slouch when it comes to detective work and she does an impressive job of constructing aspects of Eileen’s life in a way that has the ring of truth about it. This is especially true when it comes to the contribution Eileen made to Orwell’s time in Spain during the Civil War. Funder focuses on Eileen’s time in Barcelona and her administrative and organisational role with the ILP. Her and George’s escape from Barcelona as the Stalinist factions hunt them down is almost an adventure story in its own right. And, of course, Funder is quite right when she says that Eileen’s role gets no recognition from Orwell in Homage to Catalonia – you’d barely notice she was even there in his narrative.

And, yes, Orwell was capable of being astonishingly self-centred, dismissive of others, pig-headed and distressingly prejudiced towards homosexuals and women. I think his often clumsy, thoughtless, unpleasant womanising is well established but the longer this book goes on the more Funder seems intent on turning Orwell into a monster. By the end, it would be easy to think that Orwell had absolutely no redeeming features and spent his time prowling for sexual gratification almost as a deliberate slight to Eileen.

I can’t help but feel that the problem is that Funder is a little bit in love with Eileen (or at least with the idea of Eileen) and that has led her to read the evidence in a way that casts her, not Orwell, was the powerhouse behind the partnership. I’m afraid that this feels a step too far for me.

It seems undeniable to me that Eileen and George were yoked together in a way that is probably hard for those outside the relationship to really understand or appreciate. Yes, George was unfaithful but, almost certainly, so was Eileen during the time she spent in Barcelona. Yes, Orwell was a self-centred beast at times but Eileen never leaves him - and remember, Funder would have us believe Eileen was a strong, capable woman who surely would not stay with someone unless she wanted to. Despite Funder painting a picture of neglect and exploitation on Orwell’s part, the two were tight enough to go ahead with the adoption of a son barely 12 months before Eileen died unexpectedly. Rachel Cooke puts it this way in her review of the earlier Topps biography:

“If Eileen appears, to us, to have given up her own life – after a series of dead-end jobs, she was studying for an MA in educational psychology when they met at a party – it was surely only in the cause of finding a role for herself; of landing a job that really seemed to matter. I don’t believe, as some of Eileen’s friends did, that Orwell was oblivious to his wife’s suffering. Nor do I think that she longed seriously to escape it. Such strife was somehow necessary to them both. It bound them together.”

There’s plenty in the book to admire but also plenty that will infuriate by overstatement. Funder is right to highlight the way in which patriarchal institutions and male artists eclipse and minimise the role of women but the stories are more complex than the saint and sinner dichotomy this book tends towards and certainly I think that was true of Orwell and Eileen’s relationship.

By the end of the book I felt that Funder had made a strong case for the idea that Eileen's contribution to Orwell's work needs re-evaluating but her determination to put Eileen at the very centre of the partnership - the prime part of the overall creative output - seems to me to seriously overstate her role. Orwell was most certainly a difficult man to live with for all the reasons cited before but he can't have been the rather charmless figure Funder reduces him to because many others (including, presumably, the women with whom he had his affairs) found to the contrary

Terry Potter

November 2023