Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 06 Jul 2023

posted on 06 Jul 2023

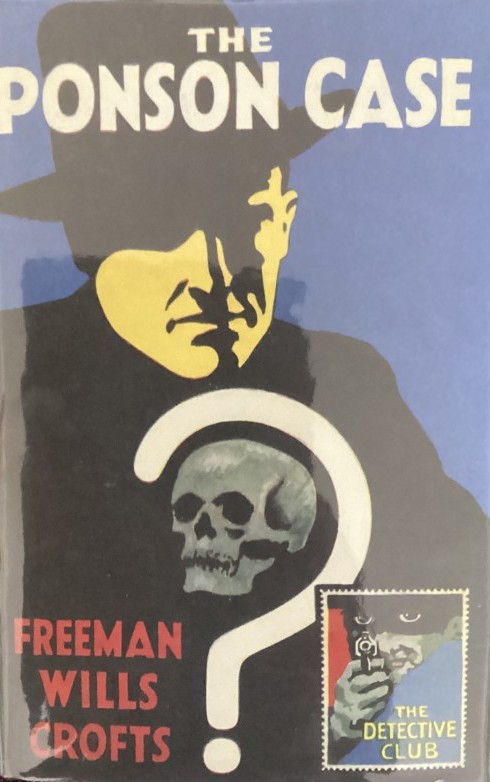

The Ponson Case by Freeman Wills Crofts

When I read Crofts’ first novel, The Cask, at the start of the year, I was impressed by the way he created a knotty mystery that he unwound in forensic detail, giving the reader the chance to have exactly the same information about the case that the investigating policeman in the story has. This made what was a comparatively simple mystery of a body in a barrel stay compelling over the best part of 400 pages. Detail was everything.

The Ponson Case was Crofts’ follow-up to The Cask and uses a very similar technique, setting out the case and the investigation in minute detail, allowing every twist, turn, revelation and frustration of the investigating officer to be shared by the reader. But there is one major difference: where that was beguiling in The Cask it becomes downright irritating in The Ponson Case.

So, why doesn’t this mystery capture the reader in quite the same way as his debut did? The first problem is in the nature of the mystery itself, which at no point really grips. Rich, self-made man, Sir William Ponson is found dead floating in the river near his house. It quickly becomes clear that this was no accident – the corpse has a brutal blow on the back of the head that seems to account for his death. Very quickly it becomes clear that there are only two viable suspects – his son Austin and his nephew Cosgrove – both of whom stand to benefit financially from the death. And to spice up the mystery a little, there is evidence of another unknown person on the crime scene and we know from the outset that finding the identity of this mystery individual will probably be the key to the death.

And that’s about it as far as plot is concerned. Although Crofts’ throws in some interesting motives and not a few red herrings, the core mystery remains uncomplicated and all our attention has to be focussed on the process of investigation and the peeling back of the onion layers. In my view, although this is skilfully handled, the mystery itself is fundamentally dull and if methodical detail doesn’t hold your attention, there’s not much else here for you.

The other difficulty for me was the characterisation. Both central suspects are oddly cardboard figures, we don’t get to know the victim at all and the final unveiling of the mystery character is, I think, unconvincingly contrived. The biggest disappointment, however, is the police detective whose investigation we’re sharing: he’s a really dry stick. Since the arrival of Sherlock Holmes in the crime fiction genre, we’ve become accustomed to detectives, professional and amateur, who have charisma or character but Crofts’ creation here, Tanner, has very little to distinguish himself other than a commitment to being doggedly meticulous.

The only saving grace in the cast turns out to be that rare fictional phenomenon of the first half of the 20th century – a strong, intelligent woman. Lois Drew, Austin Ponson’s fiancée, turns out to be the rational, intelligent, loyal and driven individual who keeps the second half of the novel afloat – and about the only one who becomes anything like three-dimensional.

I have read other reviews of the book by more obsessive crime aficionados than me who think this is an excellent book – and excellent for most of the reasons I thought it mediocre. So, this is an occasion where I feel completely justified in saying that this is a book to read and make your own mind up about because some will love it and some may well share my lukewarm sentiments.

Reprints of the book, such as the one I read and which is pictured here, can be found for under £10 in paperback but double that for hardback. Should you want an original first edition, you’d better have deep pockets and wave goodbye to several hundred pounds.

Terry Potter

July 2023