Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Jun 2023

posted on 22 Jun 2023

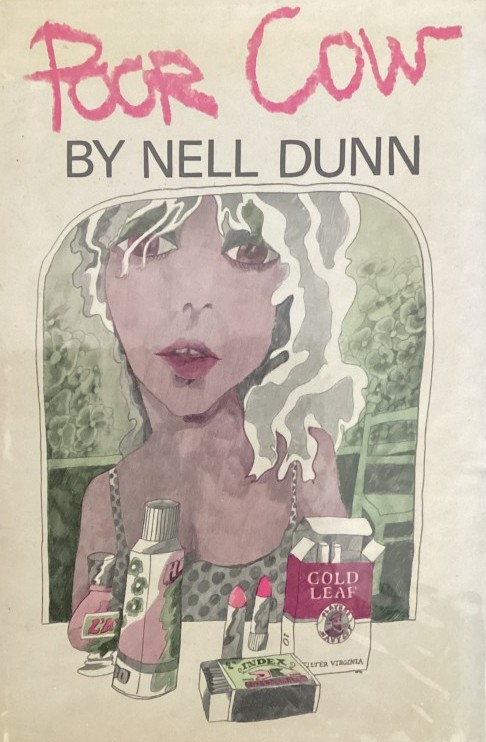

Poor Cow by Nell Dunn

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the emergence of a genre of literature that presented an uncompromising portrait of life in working class communities in Britain attracted the label of ‘kitchen sink’ dramas. This was a term that was meant to capture the gritty social realism that was their whole raison d’etre – the stories were stories of domestic and economic survival in a world where the odds were permanently stacked against the protagonists. These novels (and theatre playscripts) stood out in stark contrast to the social milieu that preoccupied the likes of Virginia Woolf, E.M. Forster and a legion of other middle and upper class writers who had so dominated the literary landscape.

That is not to say, however, that all of these social realists were themselves from or of the working class – far from it. A number of these authors, including Nell Dunn, were in fact middle class observers of the working class – a fact that has led to considerable debate about the validity of such writers adopting a working class point of view. How much of this is poverty or class ‘tourism’ – or even voyeurism - and what authenticity does a fiction have where the voice is assumed by an author rather than one that comes from genuine experience?

These are important questions and all of them are germane to Poor Cow but to do justice to the issues that are raised by this debate would require a lengthy essay rather than a short book review. The fact that this important hinterland is there, however, is worth bearing in mind if you decide that this is a book you want to explore.

22 year-old Joy has just had a baby. She’s married to Tom, an inept career criminal and when he’s sent to prison, she and baby Johnny move in to live with her Aunt Emm. Her whole life has been a hand-to-mouth experience but somehow Joy’s vitality and belief in something better has remained in tact despite the terrible physical deprivations and the amoral environment she lives in.

Joy isn’t necessarily heartbroken to be separated from Tom because this allows her to strike up a relationship with Tom’s mate, Dave – who she genuinely seems to have deep feelings for and with who she can imagine a future of sorts. But Dave is also a hopeless crook and ends up in prison, triggering Joy’s return to Auntie Emm.

We get to see Joy’s semi-literate correspondence with Dave while he is in prison and we get to see how she is a rather vibrant mix of innocence and experience. While the men are locked away, Joy’s world expands – but not necessarily in the conventional way you might expect. Working as a part-time barmaid and sex worker she discovers she has power – sexual power if not economic or social power.

Ultimately, Joy will never escape her world but she can shape the world she’s destined to live in. Her fierce dedication is reserved for her son and what she does, she does for him and, inevitably, for the best life she can create for herself.

There’s something uncomfortably condescending and a little prurient about the way Dunn characterises Joy’s letters – the terrible spelling and clumsy constructions feel almost farcical at times. The degradation and hardship comes across as grotesque parody and the overall world she creates isn’t so much ‘kitchen sink’ as ‘under the kitchen sink’. However, having said that, it clearly wasn’t Dunn’s intention to use the novel as campaigning material but to try, however, incompletely, to give a voice to people whose words had, at that time, no way of being heard.

Paperback copies of the book are readily available for well under £10.

Terry Potter

June 2023