Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Jun 2023

posted on 08 Jun 2023

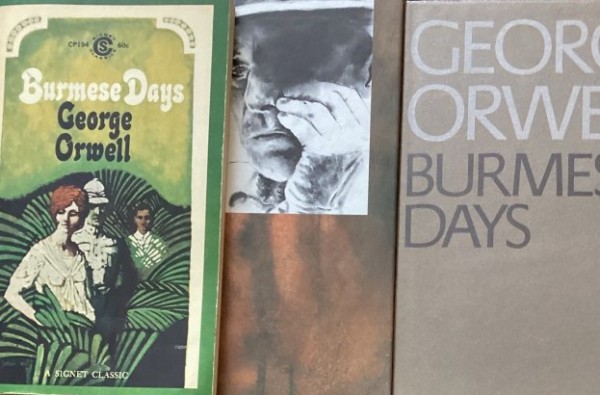

Burmese Days by George Orwell

Prior to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, the books which have made George Orwell a household name, he published four earlier works of fiction during the 1930s: Burmese Days, A Clergyman’s Daughter, Keep the Aspidistra Flying and Coming Up for Air. All of these novels have some flaws but also much to enjoy. I periodically return to them, partly for sentimental reasons because they were the first of Orwell’s books that I ever read. In this spirit I have just reread Burmese Days.

Orwell was never an especially imaginative writer and the early novels draw heavily on his own life. For this reason, perhaps, there is often something of a visible seam between the ‘real’ and the invented and to my mind this is especially noticeable in Burmese Days.

It is set in Burma (now Myanmar) in the mid-1920s, where, after several Anglo-Burmese wars, Britain had seized the territory, decreeing it to be part of India and the British Raj. Its central characters are a small group of Europeans – administration officials, civil servants, logging company managers, police officers, military personnel – and a larger cast of Burmese and Indian characters.

The key theme of the book is that colonial rule deforms all whom it touches, both rulers and ruled, and in some respects there is little point in describing the main characters because for the most part they are little more than stereotypes whose primary function is to illustrate this. John Flory is an interesting and possibly somewhat Orwellian figure, however, a self-loathing imperialist who has learnt enough about the moral corruption of British colonial rule to hate the Europeans he must live with and to loathe himself and his own part in it – especially the shameful, wasted life he has led, its drunkenness and debauchery and the string of Burmese mistresses he has used and abandoned (and, he belatedly realises, consequently ruined).

The story centres on the intrigue and scandal that grips the European colony and its European Club when new laws require all clubs across the British Empire to elect at least one non-European member.

The tensions arising from this coincide with the arrival in the colony of Elizabeth, the beautiful young niece of the Lackersteens. Elizabeth has been orphaned by the early death of her parents and – albeit reluctantly – her aunt and uncle have offered to look after her. Prompted by her socially aspiring and snobbish aunt, and fearful that her English rose complexion will not last long in the tropical heat (especially not if subjected to repeated bouts of malaria), Elizabeth is also eager to find an eligible bachelor she can marry; central to the story is whether this might be Flory, who – naively, possibly deludedly – has swiftly come to see in Elizabeth a kind of salvation.

I sometimes think that of all Orwell’s novels, Burmese Days is the one in which the story is most incidental. Orwell’s primary purpose is to coruscate imperial rule and the colonial mindset and if at the time he had considered himself able to do this without any fictional trappings, then I think he would have.

Burmese Days offers a terrifying glimpse of the morally deforming nature of imperial rule – especially the bitter, corrosive almost hysterical racism of the imperial mind – but it doesn’t work well as a novel. Its characters are largely one-dimensional, its story-telling wooden and laborious and there is a good deal of descriptive writing – actually rather good – of a kind that the older Orwell would increasingly avoid.

And yet despite these faults, Burmese Days is important on several counts: first, it is somewhat rare in being an impassioned denunciation of colonialism written from within the imperial experience; second, because it helps set in context Orwell’s later and more nuanced anti-colonial thinking, which was very much ahead of its time; and third and most importantly, because it is Orwell’s own self-punishing reckoning with the time he spent in the Burmese Imperial Police force.

Burmese Days certainly shouldn’t be ignored, but there are certainly better novels in the Orwell canon. This review makes the case for considering Coming Up for Air as the most successful of the early novels. Personally, I think one of the best things Orwell ever wrote is Down and Out in Paris and London, the early semi-reportage work of 1933 which, incidentally, preceded all of his fiction.

Alun Severn

June 2023

Books by and about Orwell elsewhere on Letterpress:

Orwell’s Message: 1984 and the Present by George Woodcock

Critical Essays by George Orwell

A Clergyman’s Daughter by George Orwell

Orwell’s Nose by John Sutherland

Rereading George Orwell’s Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters

George Orwell: A Life in Letters, edited by Peter Davison

The Girl From The Fiction Department: A Portrait of Sonia Orwell by Hilary Spurling

Classic Covers: Denis Piper’s artwork for George Orwell’s novels

Coming Up For Air by George Orwell

Animal Farm by George Orwell illustrated by Ralph Steadman

Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit