Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Mar 2023

posted on 08 Mar 2023

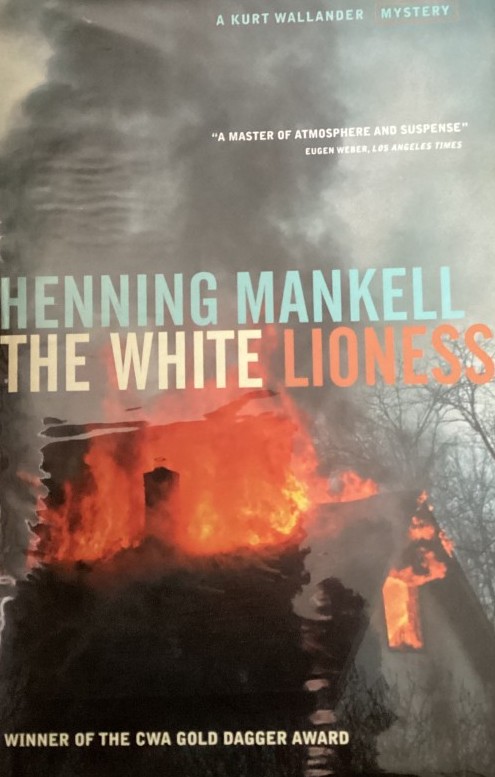

The White Lioness by Henning Mankell

Originally published in the UK in 2003, Mankell’s third instalment of his series of crime novels featuring his reluctant Swedish small-town detective, Kurt Wallander was written and released in Swedish almost a decade earlier. The Wallander series is, in many ways, the prototype for the wave of crime novels that became labelled ‘Scandi-noir’ and Wallander himself the template for the damaged, introverted but intuitively brilliant policeman that has now become almost de rigueur in popular fiction.

Although some characters and a little of the action in The White Lioness references the preceding title, The Dogs of Riga, knowledge of the plot of that book is not essential to an understanding or enjoyment of this one.

Wallander is back in his small home town of Ystad when a seemingly motiveless murder takes place. A young, female estate agent of impeccable background goes missing only to be found shot in the head and dumped down a well. Who could have done such a dreadful deed and why?

Well, that’s where the story takes a bit of a swing away from the standard detective tropes. As readers, we already know and are well ahead of the police investigation. It’s certainly not a plot-spoiler to tell you that this completely innocent young woman was in fact summarily executed by a trained assassin fearful that she may inadvertently have stumbled on his hideaway.

From this launchpad a story develops that will involve a plot to kill Nelson Mandela by members of the South African secret services who can’t reconcile themselves to President De Klerk’s decision to share power and dismantle the Apartheid regime; a Russian hired killer who finds himself in need of new employment following the collapse of the Soviet Union; displaced Russian criminals living in Stockholm; and two would-be black assassins sent for training in Sweden and finding themselves on Wallander’s doorstep.

As the plot unfolds, the reader is offered the chance to watch all this, as it were, from of distance. We know what’s going on and there’s essentially no mystery to resolve: instead, we get the chance to see the police, and especially Wallander, trying to figure all this out with only an incomplete set of jigsaw pieces to help make up the picture. More importantly, we are offered Wallander – an ordinary man in just about every way except his razor-sharp police instincts – to identify with and it is his jeopardy we share when both he and his daughter are menaced by the Russian psychopath, Konovalenko.

In Wallander, Mankell has created a character that is entirely believable and someone we genuinely care about. But this, perversely enough, creates the key weakness of the book. The progress of the plot requires Mankell to split the action and the focus between Sweden and South Africa and the developments in the South African machinations become more prominent as the story moves along. This means that Wallander himself is rather side-lined and the nexus of our involvement tends to get disbursed and with it the tension also dissipates.

In those moments when Wallander is in life and death struggles with the seemingly indestructible Konovalenko, I was reminded in atmosphere and execution of some similar confrontations between good and evil in James Lee Burke’s Robicheaux series of U.S. crime novels and then it felt, for the reader, like a moment to really hold your breath. But then the narrative switches again to South Africa and somehow the air goes out of the whole confection.

But I don’t want to sound too negative here. It’s still a good and gripping read but a bit of editing to lose a hundred pages and trim the details of the South African end of the plot would, I think, have paid dividends.

Paperback copies of the book are readily available and can be purchased second hand for about a fiver.

Terry Potter

March 2023