Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 Jun 2022

posted on 09 Jun 2022

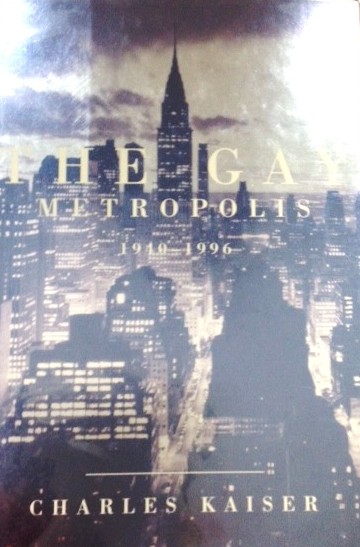

The Gay Metropolis 1940 – 1996 by Charles Kaiser

Kaiser is a journalist who has previously been a New York Times reporter and Newsweek editor – and it shows. He writes this historic overview of homosexuality – gay and lesbian – in something that feels like a hybrid of academic research, racy news copy and private revelation. The effect is to give the text a pace and accessibility that makes the book a breeze to read and, judging by the reviews it received on its release, was a key strength that critics and commentators picked up on.

Kaiser takes a decade by decade chronological approach to the development of what we’d probably now refer to as ‘gay culture’ and much of it is a potentially tragic story of hatred, discrimination and exclusion. But Kaiser, whilst acknowledging these terrible social injustices, doesn’t just produce of a tale of misery but remains steadfastly linked to a story of positivity. What Kaiser is describing is always a forward journey towards the light and away from the darkness of discrimination and he makes this explicit in his introduction when he says:

''This book tells the story of an amazing victory over adversity: how America's most despised minority overcame religious prejudice, medical malpractice, political persecution and one of the worst scourges of the 20th century to stake its rightful claim to the American dream -- all in barely more than half a century. No other group has ever transformed its status more rapidly or more dramatically than lesbians and gay men. When World War II began, gay people in America had no legal rights, no organizations, a handful of private thinkers and no public advocates. . . . A quarter-century later, gay people have completed the first stages of an incredible voyage: a journey from invisibility to ubiquity, from shame to self-respect and, finally, from the overwhelming tragedy of AIDS to the triumph of a rugged, resourceful and caring community.''

Throughout the book Kaiser falls back onto anecdotes and case studies involving artists, film stars, musicians and politicians which gives the reader the sense of being let into the world behind the curtain, the private world we don’t usually get to know about. This is a bit voyeuristic and titillating – a popular journalistic technique – and while it keeps the reader attached, the drawback is that it makes the bigger issues too particular and specific and risks losing sight of the bigger picture.

The book title and blurb suggest that this study is going to focus on gay life in a specific metropolis – New York – and while this is city acts as the nucleus and perhaps the driving force for something that could be thought of as a gay rights movement, the notion of ‘metropolis’ is given a very much more flexible and organic identity. This is, in effect, the history of gay and lesbian identity in the wider USA.

This isn’t something that Phillip Lapote reviewing the book for The New York Times in 1997 found congenial:

“Finally, what are we to make of the ''metropolis'' part of the equation? The book's title promises a unique cross-fertilization of two flourishing research areas -- gay studies and urban studies. There are, indeed, evocative passages about New York's gay bars, haunts and social subsets; but much more could have been done to unravel the intersections between minority and municipal history by uncovering the patterns of gay neighborhoods and gathering places, including those outside Manhattan. Nor is it entirely clear why the narrative hops around to Washington, San Francisco, Jerusalem, Paris and so on, when the subject is ostensibly gay life in New York. The introduction does offer an excuse by saying that ''the figurative gay metropolis is much larger: it encompasses every place on every continent where gay people have found the courage and the dignity to be free.'' This sounds grand, but what does it mean exactly? Are the many homosexuals who live in rural communities automatically ''metropolitan'' by virtue of their courage and dignity?”

And here’s another problem. Can this really present itself as a history of gay and lesbian life and identity when its clear focus is on male homosexuality? It’s hard not to get the impression that the occasional diversion into the history of lesbian lives is bolted on to the central, main theme as something of an afterthought and I found this troublesome.

It wasn’t until I’d finished the book that I discovered that Kaiser had recently updated his history in a new edition to bring it into the 21st century – continuing the theme of steady positive progress despite the obstacles, set-backs and continuing hostility that still exist.

Copies of the book can be found easily for under £10 although the updated version might cost you a little more.

Terry Potter

June 2022