Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 06 Jun 2022

posted on 06 Jun 2022

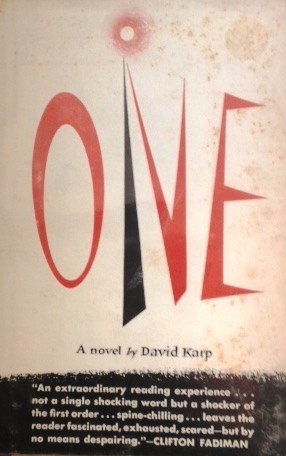

One by David Karp

New Yorker, David Karp (1922 – 1999) is best remembered for his 1953 novel, One which, alongside George Orwell’s 1984 and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We is often to be found in lists of books that define post-Second World War dystopian fiction and Cold War anxiety.

Like Orwell and Zamyatin, Karp is concerned with the functioning of totalitarian states but unlike the other two, Karp’s vision is, on the surface, a less brutal and more reassuring world, still firmly rooted in a recognisable 1950s society. Actually, however, the feeling that we’re dealing with a less aggressive, more mundane view of what a totalitarian state might look like, is slowly and worryingly undermined as the story of Professor Burden unfolds.

Burden, an academic and enthusiastic supporter of the State and a believer in its benevolent purpose, submits regular spying reports to a government department on the behaviour of his colleagues who may or may not be, consciously or unconsciously, committing ‘heresy’ – espousing ideas and values antithetical to the all-pervasive values of the State. When Burden’s regular report just happens to be sampled and he’s singled out for a routine interview, things spin quickly out of control and Burden finds himself in the hands of interrogators keen to root out his own heresies.

One of the things that makes Karp’s book different to many other dystopian novels is that it takes quite a different approach to Burden’s interrogators. We see them much more as human beings with their own motivations, uncertainties and ideological doubts. The Professor is put into the hands of Lark who is given two weeks to break Burden of his heresies and to effectively try out what is effectively a programme of brain-washing. Lark’s own future rests on his making a success of this new technique and he vows to take Burden’s identity apart and ‘pulverise him’, reconstructing him as, effectively, a new person.

Burden is subjected to drugs, sleep deprivation, isolation and constant questioning until eventually he wills himself to ‘give in’ and is allocated a whole new identity as ‘Hughes’. Stripped of his core beliefs in integrity, individuality and betterment, this seems a resounding victory for Lark and his methods. But, unlike Orwell who gives Winston Smith no way back, Karp allows the reader to see a chink of light in all this. As the book review site, Kirkus puts it:

“As Hughes and with a new personality superimposed he is a triumph for Lark -- until a chance question from a new friend reveals that the spark is still alive and that the ""new"" man carries the seeds of destruction to a controlled society. “

In my view the power of Orwell’s totalitarian vision lies in the fact that he explicitly crushes hope – the idea that the State may control what you do but they ultimately can’t control what you think is the central pearl of hope that is whisked away by Orwell. Here Karp leaves that hope intact and suggests that all totalitarian regimes will ultimately founder on the central core of positivity that makes humans human.

One is in print as a 20th century classic paperback but is quite expensive. You might want to seek out the previous Penguin Modern Classic edition which you will pick up second hand for under £10.

Terry Potter

June 2022