Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 May 2022

posted on 19 May 2022

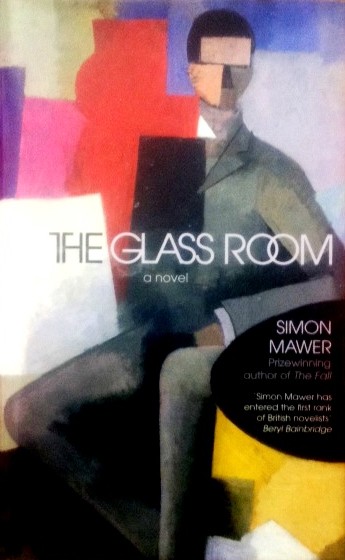

The Glass Room by Simon Mawer

Shortlisted for the 2009 Booker Prize, this novel, as its title suggests, puts architecture – political, social and domestic – at its heart. In Czechoslovakia between the wars, renowned Modernist architect, Rainer von Abt, accepts a commission to build a house for the newly married and wealthy Viktor and Liesel Landauer. Eagerly rising to the challenge, von Abt insists on banishing all decoration in favour of linear, clean lines and a feature living space – the glass room – that has a single internal wall constructed of a sheet of unbroken onyx (and, we are told, costing on its own as much as the average house). The house is a symbol of the new Europe – or at least what optimists believed the new Europe could be – and it is destined to accommodate and reflect the turbulent years that were to come.

Viktor and Leisel are destined to find their future belongs elsewhere – Viktor is a Jewish industrialist who manages to escape his homeland, accompanied by his family and mistress, as the Nazis engulf the country. Those left behind, including Leisel’s shockingly ‘modern’ girlfriend, find that the German invaders are puzzled by the house and its feature glass room but adapt it for use as a centre for the genetic study of inferior races.

As the rise of the Nazis turns into their retreat and fall, the house gives way to occupation by the incoming Red Army and this new incoming tenant finds itself equally puzzled by the vision of life the glass room represented.

By the end of the book – and I’m being careful not to uncover the threads of the story because you’ll want to follow those for yourself – it’s clear that the metaphor of modernist architecture has dominated not just the central conceit of the book but the writers approach to his writing style. As Ian Sansom noted in his review for The Guardian in 2009:

“he purges his sentences of metaphor and simile, preferring instead the devices of parallelism and symbolism. Thus, through balance, proportion and careful arrangement of both sentences and plot, he transcends mere cleverness to become profound”

There is something of a battle going on in this book between the infrastructure he has built to keep his novel on track and the more anarchic demands of the life stories that emerge from his characters. The relationship between Viktor, his mistress and, subsequently, his wife’s participation in that affair has a life of its own and, like life lived in the glass room, our viewing is essentially voyeuristic. When they are forced into exile, our voyeuristic attention turns instead to the increasingly complex life of Leisel’s best friend. These are stories that seem to be demanding their own space rather than to be framed in the proscenium arch of the glass room.

This is undoubtedly a rich and complex book of ideas as well as character but the meticulous plotting has its drawbacks and, by the end, the late 20th century conclusion that draws the story back around to reflect on itself all feels a bit artificial.

I think other reviewers were rather split on their opinion of the novel and tended to come down on the side of this being a beautifully written but ultimately flawed piece of work. You can make your own mind up by buying a copy that you’ll spend less than £5 to find in paperback.

Terry Potter

May 2022