Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 06 Apr 2022

posted on 06 Apr 2022

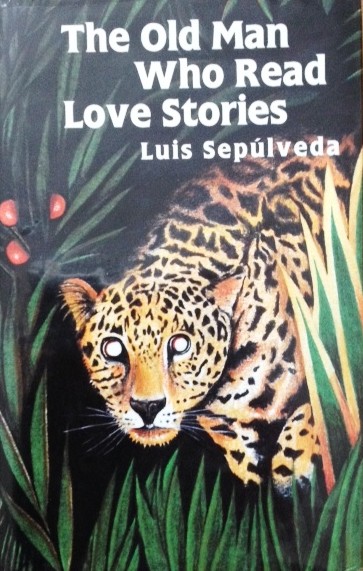

The Old Man Who Read Love Stories by Luis Sepulveda

Luis Sepulveda’s life story (1949 – 2020) is the kind that makes you feel completely inadequate and humble. He was a student activist, studying theatre, and member of the Chilean Communist Party. As a supporter of Salvador Allende he found himself fighting the right-wing Pinochet regime until he was imprisoned and exiled – despite the best efforts of the German branch of Amnesty International who interceded on his behalf.

He was sentenced to exile in Europe but slipped arrest in order to stay in South America and, through the establishment of radical theatre groups he led an underground fight for what he saw as progressive democracy against the growing forces of repressive autocracy that was gaining ground across the region. He eventually found a home in Ecuador under the sponsorship of Jorge Enrique Adoum, an esteemed Ecuadorian writer, poet, politician, and diplomat, where he was able to resume his theatrical work. It was during this time that he became a member of a UNESCO deputation assessing the impact of colonialism on the indigenous Shuar people.

In 1979 he joined the fight for liberation in Nicaragua and, following the success of the revolution, he finally moved to Germany. The trip to spend time living with the Shuar had ignited Sepulveda’s passion for ecology and in the 80s he joined Greenpeace and acted as a crew member on their intervention boats.

His first breakthrough novel, The Old Man Who Read Love Stories, was published in 1989 (and translated into English in 1993) and draws heavily on his experiences with the Shuar. It seems at first as if it’s a simply written fable of the way rapacious colonial capitalism is destroying the Amazonian habitat and how Western mores stand in direct opposition to the intuitive values of the Shuar who contrive to live in a way that is simpatico with the natural world around them.

Whilst that reading is certainly part of this slim but rich novel, there’s a subtlety and nuance that gives the book an added dimension. The old man at the heart of the story, Antonio Jose Bolivar, is himself a product of colonialism who, despite living with the Shuar and learning their ways, finds he can be like them but he can never be one of them.

When an ocelot, whose young have been killed by poachers, goes on a killing spree to avenge her loss, the authorities in the form of the comically overweight and inept district mayor, turn to him and his legendary jungle skills to track the animal down. It’s a task Bolivar doesn’t relish but carries out under duress - he’d much rather spend his time reading love stories, slowly, stumblingly but with relish. His preference is for novels of heart-breaking anguish and in his old age he lives for love and the life of the imagination. It’s an internal life he can’t find in the outside world – neither the rapacious gringos and the Shuar have any sense of Bolivar’s fascination for tortured love stories. In the real world life is out of joint; man and nature too often in conflict with disastrous and tragic results.

In just 130 or so page, Sepulveda manages to encapsulate a sweeping and searing indictment on the destructive nature of Western capitalism and colonial occupation – in many ways so much more effectively than the lengthy non-fiction diatribes that cover similar territory. So, it’s a tragedy to report that in 2020, Sepulveda was one of the first victims of Covid 19 as he travelled from Portugal to Oviedo in Spain where he died of multiple organ failure.

A tragic loss but we do, at least, have his books and his journalism.

Paperbacks of the book are readily available on line and you’ll pay less than £10 for a good copy.

Terry Potter

April 2022