Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 30 Mar 2022

posted on 30 Mar 2022

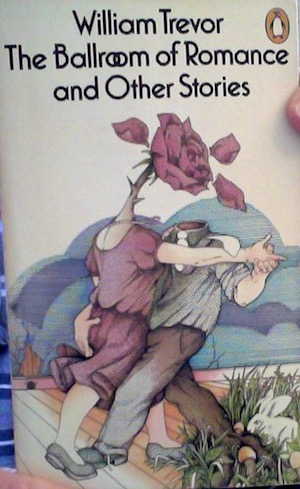

Rereading The Ballroom of Romance & Other Stories by William Trevor

After a gap of far too many years I recently began to explore William Trevor’s short stories again.

When he died in 2016 aged 88 he left at least a dozen collections of short stories. I began by hunting out my very old Penguin paperbacks of the first three – The Day We Got Drunk on Cake (1967), The Ballroom of Romance (1972) and Angels at the Ritz (1975) – and began reading with the second of these.

Before I began this rereading, if you had asked me what I loved about Trevor’s short stories I would have said their humour, their impeccable ear for dialogue and the deeply evocative settings of provincial Ireland in the late-60s and early 70s. But my memory had played tricks again and I found that remarkably few of Trevor’s earlier stories are in fact set in Ireland. Of the dozen stories in The Ballroom of Romance, for example, only three are set in Ireland.

And yet to my mind his stories with an Irish setting are his richest and most accomplished. This is ground that Trevor is certain of and knows intimately from first-hand experience, after all – the frustrations and disappointment and isolation of rural small town life; the little dance halls out in the countryside into which the ‘hill bachelors’ crowd on a Saturday night, seeking romance; the young men and women unable to seek wider horizons or better lives because their ageing parents need them; the limited educational opportunities of the Christian Brothers’ schools playing out over a lifetime. The humanity, the depth of observation, the generosity of spirit, the effortless invention, the gentle humour, the melancholy, the moments of redemption and the deep vein of stoicism that a hard country life requires – all these and more are there in the ‘Irish stories’.

But I was surprised to be reminded that these early stories of disappointment and lost love and stoicism are as likely to take place in London or the Home Counties or at the English seaside or abroad as they are rural Ireland. I had forgotten what an extraordinary range Trevor has. He seems able to write himself into almost any situation and what marks out these stories is the extraordinary parade of humanity moving through their pages. In an early review the critic Auberon Waugh described the stories as “well written, meticulously observed, ingeniously constructed, generously conceived – deserving to be treated as classics of the form.” And he is absolutely right. Especially I think in that bit about their being “generously conceived”. Somehow, this captures their very essence, for they are generous in spirit, they are generous in scope (not necessarily length but Trevor does seem to write at his best at around the twenty or so pages mark) and most of all they are generous in their humanity and fellow-feeling.

Writing after Trevor’s death the novelist Julian Barnes said that even his final stories were marked by characteristically “precise evasions – and evasive precisions”. But evasiveness should not be construed as meaning vagueness. You rarely finish a William Trevor story and find yourself thinking – as can sometimes be the case with other writers – now, what was that about, exactly? What most interested Trevor I think was moral ambiguity, the accommodations we all make with loss or disappointment or personal weakness, the means we have at our disposal for coping with human frailty – but in considering this he was generally unflinchingly clear.

The greatest story in The Ballroom of Romance is the title story – indeed, it may be one of Trevor’s greatest stories overall. What singles it out, I think, is the extent of the hinterland Trevor manages to deftly sketch in. The incidents in the foreground of the story take place on a particular Saturday night at the local crossroads dancehall, The Ballroom of Romance, its handful of garish coloured lights visible for miles in the evening darkness; but its hinterland is a profoundly imagined history of Ireland over the preceding thirty years or so. Frank O’Connor, the great short story writer of the generation before Trevor, said that what distinguishes short stories from novels is their “intense awareness of human loneliness”. Whether Trevor agreed with this I’m not sure, but he most certainly practiced it, allying it in his own writing with what he called the “art of the glimpse” – an ability to convey vast amounts with the kind of fleeting details one sometimes barely registers but which on reflection emerge as pivotal to one’s understanding of a scene or recollection of a period or event. Nowhere is his “art of the glimpse” technique more evident than in this story.

Now a word must be said about what I’ll call the ‘non-Irish stories’ – those that are set elsewhere than Ireland. Certainly in this 1972 collection, these stories have a quality that I struggle to put my finger on. For a start, there is often something slightly anachronistic in their tone. Characters are more likely, it seems, to be middle or upper-middle class, their settings suburbia or prosperous parts of London. Sometimes we seem to be seeing the relaxing of moral codes and attitudes that came with the 1960s, but equally many of these early ‘non-Irish’ stories feel as if they could be depicting the 1950s, perhaps even the 1940s. Some of them have a slightly macabre aspect, something psychologically unsettling, a glimpse of darkness. ‘Going Home’ and ‘The Mark-2 Wife’ in this collection both have an unsettling note of hysteria and perhaps for this reason I would mark them down a notch or two below the finest of the other stories with an Irish setting, but ‘The Forty-seventh Saturday’, a story with a London setting, is marvellous, as fine as anything Trevor ever wrote.

Wherever you choose to start with Trevor’s short stories, there are sufficient for a lifetime’s reading. They are best read slowly and savoured.

Alun Severn

March 2022

Other pieces about short stories elsewhere on Letterpress:

Rereading M.R. James’s ghost stories

The ‘lonely voice’ of the short story – rereading Frank O’Connor

Rereading Scott Fitzgerald’s short stories

Is this my summer of the short story?

Spirits of the Season: the pleasure of well-chosen ghost stories

Don’t Look Now & Other Stories by Daphne du Maurier

Selected Tales by Algernon Blackwood

Exile and the Kingdom by Albert Camus

And two William Trevor novels:

Fools of Fortune by William Trevor

Reading Turgenev by William Trevor