Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 Mar 2022

posted on 09 Mar 2022

Call For The Dead by John le Carré

Call For The Dead (aka The Deadly Affair) was John Le Carré’s first novel, published in 1961, and the one which introduces us to his greatest creation, George Smiley. Smiley makes his unforgettable debut in Chapter One and his introduction is one of the most impressive pieces of writing I’ve read for a long time. As an intelligence agent Smiley is just about everything the popular image of a spy isn’t – he’s the sort of polar opposite of the thrusting, all-action, suave and dangerous agent you might expect to find in fiction. James Bond he most certainly isn’t:

“Short, fat, and of a quiet disposition, he appeared to spend a lot of money on really bad clothes, which hung about his squat frame like skin on a shrunken toad.”

With his unlikely marriage to the unfaithful Lady Ann Sercombe at an end and his wartime covert European intelligence role at an end, he returns to England and a Government department wholly alien to him:

“ This was a new world for Smiley: the brilliantly lit corridors, the smart young men. He felt pedestrian and old-fashioned, homesick for the dilapidated terrace house in Knightsbridge where it had all begun. His appearance seemed to reflect this discomfort in a kind of physical recession which made him more hunched and frog-like than ever. He blinked more, and acquired the nickname of 'Mole'.”

He’s back but he’s not in the centre of things – an old relic that has to be found a quiet corner:

'Anyway, my dear fellow, as like as not you're blown after all the ferreting about in the war. Better stick at home, old man, and keep the home fires burning.'

As part of his new role, Smiley undertakes a standard security clearance on Samuel Fennan, a former Communist Party member now working in the Foreign Office. Smiley considers the interview entirely satisfactory and is preparing to clear Fennan of any lingering suspicion of duplicity when he discovers Fennan has suddenly killed himself – and what is more shocking, seems to be blaming the interview with Smiley for his actions.

What follows is something more like a thriller as Smiley and the soon to be retired Police Inspector Mendel team up to try and discover the true story behind Fennan’s ‘suicide’. The two men find themselves trying to follow a thin line of clues that lead them to some unsavoury underworld minor-criminals and a suggestion that some considerably more dangerous East German links might be involved.

While trying to uncover who has been renting a stolen car from a local minor criminal, Smiley gets viciously beaten in the backstreets and hospitalised. As a result he uses his time laid-up to rethink what’s been going on and comes to the conclusion that Fennan’s widow might be the key to the whole affair.

As a first novel this is quite a debut. Le Carré just hits the ground running and holds your attention from start to finish in a seemingly effortless way despite some clumsiness in the plotting which seems unnecessarily complicated at times. There is a tendency to spell out the key points of the plot as if we constantly needed a recap and the mysterious East Germans never really come to life.

But these are comparatively minor gripes because the quality of the writing is such a pleasure to engage with – especially if you’ve had the misfortune to read some of the clunky, second-rate spy thrillers that follow in the wake of Le Carré’s novels.

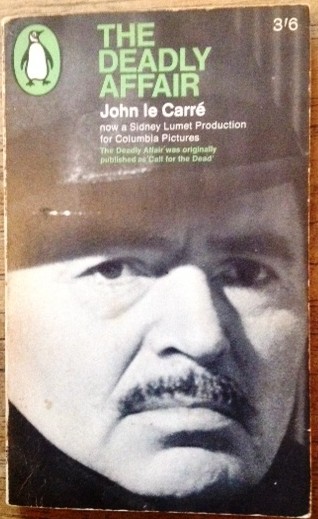

The book was made into a film in 1967 called The Deadly Affair, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring James Mason. The 1966 Penguin I read promotes that film and changes the title of the book to match the movie – which seems to me a completely unnecessary bit of advertising.

You'll find plenty of paperback editions for well under £5 but if you want a hardback first edition you'll have to raid the piggy bank and hope you've got the odd few thousand pounds going spare.

Terry Potter

March 2022