Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Feb 2022

posted on 16 Feb 2022

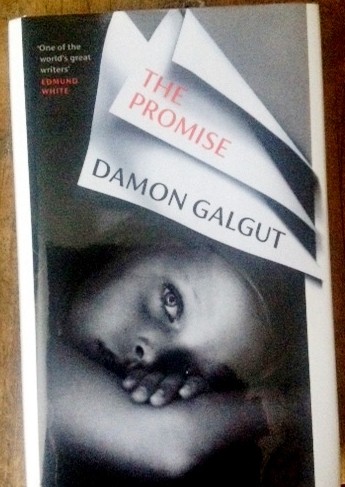

The Promise by Damon Galgut

I used to go out of my way to ensure that I read the winner of the Booker Prize but in recent years it’s felt as if the judges have put a focus on the idiosyncratic at the expense of the established. However, the most recent triumph by the South African writer, Damon Galgut decisively lays this trend to rest: The Promise is a beautifully written, intelligent and entirely engaging work of art. Galgut has made the shortlist before without success but this time he emerged as a favourite to win almost from the outset of the judging process.

This is, in its way, a the saga of a white South African farming family that is set over a period of around 40 years. It has its beginning in the years immediately prior to the fall of the Apartheid regime and follows it through to the current day. It’s the story of the way promise is squandered – the promise of a nation, the promise of individual lives, the promise of integrity and, ultimately, the way promises that are broken can’t easily be mended.

The book is structured in four parts, each roughly a decade apart, and each section features the death of one of the Swart family. The first death is that of the mother, Rachel, who, as she is dying, asks her husband, Manie to promise to give their black maid, Salome, and her family the rights to the land their house is situated on within the Swart farm land boundary. In his grief at the loss of his wife he makes her that promise which he will ultimately renage on. But, unknown to him at the time, the commitment is witnessed by the youngest daughter, Amor who is determined to see that promise fulfilled.

What follows is as inevitable as Greek tragedy. Anthony Cummins, reviewing the book for The Guardian, describes it this way:

“Manie’s failure to keep his word falls like a curse as we follow his children down the decades. Four sections, set at roughly 10-year intervals, from Botha to Zuma via the 1995 Rugby World Cup and Mbeki’s inauguration, are each named after a family member who will die; even once you’ve twigged the significance of the section titles, Galgut steals the breath with his willingness to fell his characters so randomly. Amor’s bulimic sister, Astrid, unhappily married with twins, becomes a social climber who, lured by proximity to power, cheats on two husbands; their older brother, Anton, lives in the shadow of an unrecognised crime committed while a teenage conscript deployed against black protesters during the violence of the 1980s.”

As we read through the decades and witness the ignominious deaths of Manie, Astrid and Anton, their demise comes to symbolise the trajectory of a tragic nation, blighted by the ghost of its potential and promise. It’s as if the story of the Swarts is an extended metaphor for the whole story of white rule in South Africa.

At the end, Amor, the enigmatic, quiet Swart who remains determined to follow through on her mother’s promise to give land to Salome, discovers that making good on that commitment isn’t enough to heal the scars of history. There’s no simple solution to the way a promise has been compromised by time and a growing sense of hatred has made reparation almost impossible.

Galgut – or the narrator at least – sits conducting the narrative and, at times, inserting his own presence, almost as if he’s determined to steer his assumed (white Afrikaans?) readers to his little in jokes and satirical comments. Jon Day, also writing for The Guardian, puts it this way:

“In its themes The Promise aspires to a Joycean universalism, and stylistically too, this is a neo-modernist novel. The narrator occupies an indistinct space, halfway between first and third person, drifting from tight focus on a single character to a more piercing, detached view, often within a single paragraph. There’s plenty of free indirect discourse, and sections written in something approaching Joycean stream of consciousness.”

I think in less skilful hands the politics of the personal and the public might have come across as a bit heavy-handed but Galgut is plenty good enough to pull it off with real depth and insight.

The novel is currently only available in hardback but a paperback version must be due shortly.

Terry Potter

February 2022