Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 06 Feb 2022

posted on 06 Feb 2022

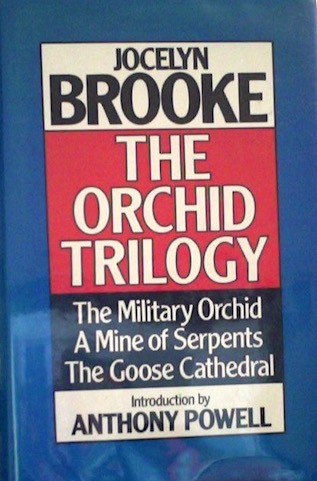

The Orchid Trilogy by Jocelyn Brooke

The novelist Jocelyn Brooke is not widely read today. His best work, the three autobiographical novels known as The Orchid Trilogy (comprising The Military Orchid, A Mine of Serpents and The Goose Cathedral), was originally published between1948 and 1950. It was republished in a single-volume hardback (Secker & Warburg) and paperback (King Penguin) in 1981 but these editions have been out of print for decades. Thankfully, a one-volume Pan Macmillan paperback is currently available.

Why some writers should so wholly fall out of fashion is a bit mysterious. Time and tastes move on and some writers are simply swept away, I suppose. In Jocelyn Brooke’s case it is a great shame because he is genuinely good and could be enjoyed by a much wider audience.

Although written largely in the lead up to and during the war, I always feel that the trilogy seems to typify that very particular strain of Englishness of the inter-war period, characterised by writers who are usually upper class, frequently gay, public school, bohemian to one degree or another, and in thrall to Proust (in Brooke’s case, with a degree of irony and self-disparagement).

What Brooke has produced in The Orchid Trilogy is a really rather cunningly contrived autobiographical fiction that is built up in layers on a foundation of his own personal obsessions. These include botany (and almost exclusively orchids), fireworks, military life, English landscape (especially as this relates to his own sense of mythology and nostalgia for a lost past) and the ‘mauve’ writers and Aesthetes that dominated Oxbridge taste between the wars (Denton Welch, Norman Douglas, Ronald Firbank, Oscar Wilde, Gide).

While the settings include Italy (both during the war and post-war), Paris and London, the dominant landscape is the rolling downs and villages of the Elham Valley and the coastal towns of Folkestone and Dover. To read Brooke is to be constantly reminded of quintessentially English visual artists such as Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden whose work similarly mythologises rural South East England (here, here and here elsewhere on Letterpress). I’ve no idea whether these artists were familiar to Brooke but it seems at least possible that they may have played a part in shaping his aesthetic sense of landscape.

What drives Brooke’s work above all else is the construction of a personal mythology and everything that is most meaningful to him is incorporated into this personal pantheon of gods and totems and fetishes. Sometimes these incorporations are quite literal – the personal joy he derives from orchid-hunting, for example; but at other times they are imaginative, with even the errors of his original childhood interpretation becoming an intrinsic part of the mythology. For example, a lifeboat house becomes the Goose Cathedral; a Kent coal mine known as The Borings becomes associated in Brooke’s mind with a race of grimy underground men capable of surviving in deep, airless chambers below the downs, the area’s profuse barrows and burial mounds becoming outposts of their underground workings.

If all this sounds rather heavy going, then let me say that for some reason it isn’t. What carries the day, I think, is Brooke’s marvellous conversational tone. In this regard I think he has something in common with Anthony Powell (they did in fact admire each other’s work and Powell wrote the foreword to the 1981 hardback reissue). Powell’s admirers similarly tend to focus on his inimitable, idiosyncratic voice and say that it is this above all else that they find addictive.

While it must be said that Brooke’s achievement is not up to Anthony Powell’s standard, equally it must also be acknowledged that The Orchid Trilogy has few real rivals. I can’t think of anything else that is quite like it. For a man who most of the time seemed to think that he couldn’t write at all and was an abject failure constantly in danger of ‘self-dissolution’, Brooke actually wrote a lot and the best of what he produced can be found in this neglected trilogy. If it appeals to you too then you will have discovered a world that will last you a lifetime.

Alun Severn

February 2022