Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Jan 2022

posted on 05 Jan 2022

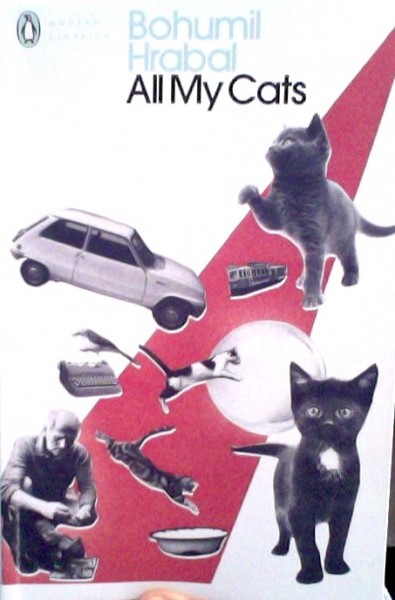

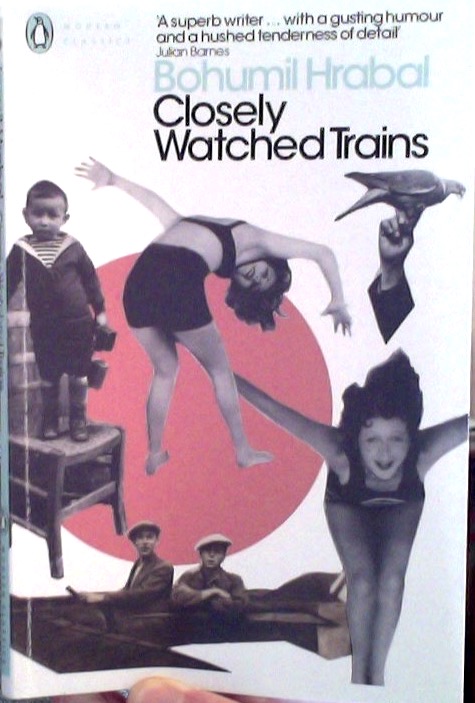

Closely Watched Trains and All My Cats by Bohumil Hrabal

I recently bought two novels by the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal, beautifully repackaged in Penguin Modern Classics editions. I bought them almost entirely because of their jackets – but not quite. I vaguely remembered that Closely Watched Trains had been filmed (as Closely Observed Trains) in 1966 by the director Jiří Menzel and that in the 70s a film obsessed friend had urged me to see it. I didn’t.

So it was with an entirely open mind that I read both of these books recently, beginning with the more well known one, Closely Watched Trains.

I think with one exception all of Hrabil’s novels are short. But this should not be taken to mean that they are slight or lightweight. On the evidence of these two, be prepared for books that are short, compact and intense but which nonetheless still manage to have something about them of the shaggy dog story. Perhaps this is attributable to the fact that under communism Hrabal was for years a banned writer, his work available only in samizdat editions and what might be called samizdat performances – readings that he (and sometimes his fans) would give in pubs and bars. The books read as if their intensity and accomplishment are more or less accidental – but this is clearly far from the truth.

Closely Watched Trains (1965) takes place towards the end of the Second World War and the final months of the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia. Miloš Hrma is a young apprentice train dispatcher at a small rural station. He is something of a day-dreamer and by his own account comes from a long line of day-dreamers, oddballs and malingerers. His father, a long-retired railwayman, toured the district on bicycle, collecting scrap. His great-grandfather was a drummer boy in the Austro-Hungarian army, invalided in 1848 when only eighteen, and lived his life determinedly drinking his relatively generous pension – and being regularly beaten up because of his relentless bragging. His grandfather was a small-town circus hypnotist. But when the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939 grandfather surprised everyone – perhaps himself too – by being one of the few to turn up to oppose the tanks. Sadly, he thought that hypnotism would turn back the young Panzer drivers. It didn’t and he was crushed beneath their treads.

When the story opens the railway station Hrma works at is consumed by sexual scandal. A more senior employee, Hubicka, has brought disgrace to the station by seducing the desirable telegraphist Virginia Svata on the station master’s prized leather couch. The puritanical, domineering station master is bellowing himself into a state of apoplexy. For him, the railway service is still possessed of the grandeur and quasi-military pomp of the old Austro-Hungarian bureaucracies and his subordinate’s offence is like spitting in the face of the late Emperor. That senior dispatcher Hubicka had also shamelessly imprinted the telegraphist’s quivering backside with messages from official station rubber-stamps added further incalculable insult.

This gives some flavour of the book – by turns melancholy, nostalgic, bawdy and somewhat hallucinatory, but also, given its setting and main subject matter, deeply serious. For this lyrical, even at times tender opening will eventually lead us to horror – as is often the case with Hrabal, I now realise – when the young apprentice Hrma decides that he will take action against one of the ‘closely watched trains’ that pass through his station: a German munitions train. I’ll let those who wish to read find out what happens for themselves.

All My Cats is a later work, written when Hrabal was in his sixties and published in 1985, and to all appearances is a short memoir about the population of stray cats the writer inadvertently amassed at his small country cottage – a sort of dacha, I suppose – where he would go to write and think, away from the bustle and distractions of the city. Again, I don’t think the apparent simplicity should be taken at face value. This funny, obsessive, repetitive book has an infinitely darker heart. A reviewer writing in the Daily Telegraph said it was “Dark and strange…it begins with warmth and fluffiness, but soon descends into Dostoyevskian horror”. Quite right.

Perhaps because there is no plot to speak of to get in the way, this novel seemed to me to reveal more about Hrabal’s methods. He was a great fan of Dostoyevsky, it’s true, but here Hrabal’s modernist experiments are also more evident. It is clear, for instance, that the dark, pessimistic vision is also saying something about the human condition, about our own capacity for cruelty and brutality, about our desire for innocence and tenderness. The repetitive, looping, circularity of the prose reminded me a little of Beckett, but a closer comparison might be the great Austrian novelist Thomas Bernard, whose own works raise complaint and pessimism and obsessive ‘kvetching’ to the level of high art – arias of pessimism and horror. I wouldn’t overstate this similarity because whereas Bernhard’s work is unrelievedly dark (but, once familiar, also very funny), Hrabal’s is altogether lighter – both in tone and in how it is accomplished.

At one point in All My Cats, a slightly unbalanced neighbour who wants to see Hrabal prosecuted for allowing his cats to slaughter birds begins to lament the death not just of songbirds but of the cattle we slaughter and eat, the “miserable Chagallian cows”, as he calls them, and it suddenly struck me that the artist Marc Chagall, whose visions of shtetl life mix the prosaic, the tender, the erotic and the fantastic, may well be key to an appreciation of Hrabal.

I have done little besides gives the slightest flavour of these two extraordinary books. Hrabal died in 1997, apparently falling from the window of a Prague hospital as he attempted to feed the pigeons. His end seems as extraordinary as his life. You also can’t help but feel that a darkly comic fate was at work to ensure him a death that might have come from one of his own novels.

I was reading All My Cats one evening on the bus home from work. A woman sitting across from me leant slightly closer. Barely audible through the face-mask she was wearing and in heavily accented English she said that she couldn’t remember how many years it had been since she had last seen someone reading Bohumil Hrabal, how marvellous he was, and yet how few people were aware of him. The rest I couldn’t make out. What was evident, however, was this: just seeing someone reading Bohumil Hrabal was for her a source of great joy. I couldn’t help wondering whether she was thinking back to an earlier time when she had sat drinking in Prague’s dark, smoky cellar bars, listening to samizdat readings from the banned novelist’s work. Sadly, face-masks and social distancing and a crowded bus were not the circumstances in which to attempt such a conversation.

If you have never tried Hrabal then do read some of his extraordinary work. Perhaps better still, as the woman on the bus said to me: “read them, read them all”. I shall certainly try.

Alun Severn

January 2022