Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Dec 2021

posted on 14 Dec 2021

Rereading WG Sebald’s Austerlitz

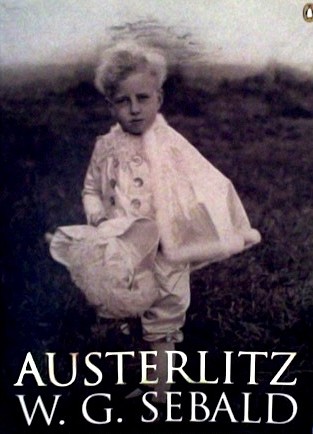

Twenty years ago, on the 14th December 2001, the great German novelist, essayist, poet, translator and academic WG Sebald was killed in a car accident. Just five or six weeks prior, his latest and perhaps greatest novel, Austerlitz, had been published. He was just fifty-seven years old.

I remember when his earlier novel, The Emigrants, was published in the mid-90s. It was the first English translation of his work and it came like a bolt out of the blue: an oblique, melancholy voice arrived fully-formed; it wasn’t immediately clear whether one was reading a lost European master from the late-nineteenth century, a previously unheard of modernist mixing fiction, reportage and ‘found’ photographs, or a memoirist. Sebald seemed all of these things, and more.

Sebald’s great themes are memory, the passage of time, loss, displacement, the extermination of European Jewry under Hitler’s Reich and the long shadows of post-war history. But what marked him out as a unique talent, a unique mind, was that generally he worked away at these themes obsessively, circling and recircling them, finding new approaches, new topics, new facets of history that somehow, often without actually naming the underlying matter in hand, nonetheless seemed to cast new light on the fractures and dislocations and reverberations of the twentieth century’s defining horror.

That will make Sebald’s work sound grim and forbidding, whereas in fact it is exquisite. His novels mix the real and the imagined in prose of great beauty that is often deliberately archaic in tone. He acknowledges a debt to the great Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard and his prose shares some of the same trademarks – long, infinitely winding passages, a structure that seems obsessive and sometimes repetitive, gradually building up in rhythm and intensity, an intense melancholia and loneliness – but is generally less dark and almost never as enraged, as scabrous, as vitriolic as Bernhard sometimes is.

Sebald’s approach was perhaps more oblique, more avowedly experimental in his earlier novels, Vertigo, The Rings of Saturn, and the four inter-linked short stories or novellas that make up The Emigrants. But when I say experimental this should not be taken to mean experimental in any contemporary sense: Sebald’s modernism was always that of the very early twentieth century, a sort of retro-modernism. In these earlier works Sebald seemed on the one hand to mine European history for fresh subject matter, while on the other often exploring – in a slightly tongue-in-cheek tone – the psychic disturbances of a usually unnamed narrator, a sort of Sebald doppelganger, whose time seems to be spent in long, lonely melancholy walks through winter landscapes, East Anglia, the Fens, Suffolk, Antwerp, Prague… The echoes of German romanticism, the traditions of ‘Winterreise’ and of early modernist stream-of-consciousness techniques are pervasive, but they are deeply woven into the fabric of Sebald’s work, so much a part of the writer’s sensibility, that they are never intrusive, always necessary.

And then, just weeks before his tragic accidental death, came what many regard as the book that marked his crowning achievement, perhaps the culmination of what he had been working towards in all of his earlier work: Austerlitz.

Austerlitz is a more conventional and perhaps more explicit novel. It is the story of Jacques Austerlitz as told to an unnamed narrator and it concerns Austerlitz’s gradual realisation that he has lived a life haunted by circumstances he cannot name and has – albeit subconsciously – refused to recognise: that his parents were murdered during the Holocaust and that he arrived in England in 1939, alone and aged just four-and-a-half, having been despatched by his mother on one of the few kinder-transports evacuating Jewish children from Prague.

But this story is told with Sebald’s trademark reticence – at least initially. The narrator recounts the various times he has happened to meet his old friend Austerlitz, sometimes in the unlikeliest of places – Liverpool Street Station, Greenwich Observatory, old railway hotels – and the unending conversation they pick up, Austerlitz often unerringly continuing the story precisely where he left off months, perhaps even years earlier. There are lots of reasons why this narrative device should stretch credulity and fail to work. That it does work is down to the sheer intensity and detail of Sebald’s imagining. I never read Sebald feeling that I am reading something ‘made up’; I never feel that I am reading a ‘plot’. I am, simply, reading something that has been thought – but so intensely and so carefully, and so obsessively and over such extended periods that to question its reality seems beside the point. In this sense, whenever I read Sebald I feel that what I am reading is ‘true’.

Rereading Austerlitz for the third time I find myself wondering yet again whether this is the book I would begin with if I were reading Sebald for the first time. There is no doubt that it is a more straightforward novel, significantly less oblique and enigmatic than his earlier work. Its subject is closer to the surface and this perhaps makes it more approachable. But I do sometimes think that in achieving this Sebald sacrificed some of the mysteriousness that makes Vertigo and especially The Rings of Saturn so marvellous.

Anyway, what is certain is that wherever one starts in reading Sebald, one is encountering a genuinely great European novelist whose every book seems written at the height of his powers. He is one of those writers whose relatively slender output constitutes an entire world – and once discovered, it is a world you cannot imagine being without.

Alun Severn

December 2021