Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Dec 2021

posted on 05 Dec 2021

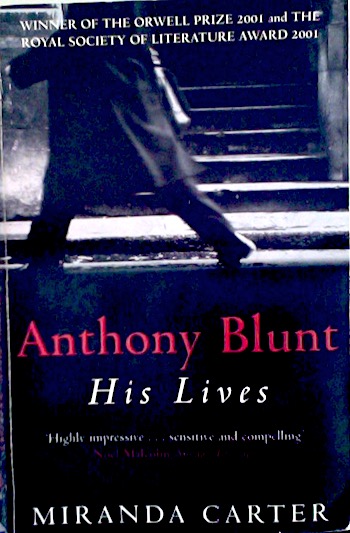

Anthony Blunt: His Lives by Miranda Carter

The Cambridge Five spy scandal: upper class dons and undergraduates forming Communist Party cells at Cambridge University in the 1930s; the recruitment of some as Soviet spies; the defection in 1951 of two of the first named spies, Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess; the subsequent defection in 1963 of Kim Philby, the eventual confession of John Cairncross…

What a strange and compelling story it is. But its truly lasting fascination I think derives from events in 1979, when the then-new prime minister Margaret Thatcher revealed in parliament that Anthony Blunt – art historian and art world grandee, renowned Poussin scholar, director of the Courtauld Institute and Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures – was the fifth member of the Cambridge spy ring. The revelations about Blunt offered a powerful and emblematic illustration of how far into the very heart of the British establishment this scandal reached, endowing the story with a louche, sinister glamour that continues to be irresistible to historians, biographers, dramatists and spy novelists alike.

Carter’s book is hugely ambitious in the complex and sometimes convoluted story it seeks to tell, for the life of Anthony Blunt cannot be told separately from the story of the Cambridge spy-ring and the global geo-politics of the 1930, 40s, 50s and 60s, and she weaves these narratives together brilliantly. Her prose sometimes shows the strain, however, and I found there were many instances when I needed to reread long sentences in which too many ideas seemed to be competing for attention. Perhaps with such a complex and far-ranging story this is inevitable, but there were times when I couldn’t help feeling that a slightly more graceful prose style might have solved some of these problems.

I can’t imagine that any other book will ever offer the insights that this does into the life – the lives – of the man who was Anthony Blunt. In that sense, Carter’s biography is probably definitive. And yet I finished it still unclear about what motivated Blunt. He was never truly a communist; he wasn’t even all that interested in the contemporary politics of his age. Certainly, there was a period when his outlook was avowedly marxist and his aesthetic and artistic writings reflected this – but often unconvincingly and clumsily and almost invariably in ways that he subsequently retracted. The single most powerful justification he ever offered for his spying was that he and others were fighting fascism, not supporting Moscow. Beyond this, he remains entirely enigmatic, impenetrable. Perhaps it was merely egotism? There is no doubt that status and power (albeit discreetly and elegantly exercised) were important to Blunt and there is absolutely no question about his appetite for work in pursuit of this. Or perhaps spying was so close to the kind of clandestine life homosexuals had to lead in the decades prior to decriminalisation that it was second nature, the internalised habits of a lifetime played out on a larger political stage? Ultimately, I think it is impossible to know and the fact that Carter’s book doesn’t offer a definitive answer is not to its detriment. That answer doesn’t exist.

What is abundantly clear, however, is the appalling toll this double life exacted. Blunt lived longest, but like all the other Cambridge spies he died anguished and disgraced, his death hastened by drink and decades of stress. His partner of many years, John Gaskin, fell from their mansion block flat – possibly a suicide attempt – and never really recovered from his injuries. Blunt became his carer. After Blunt’s death in 1983 Gaskin finally did kill himself by jumping under a train.

But despite this, Blunt exhibited the quality he most admired and most associated with Poussin, the ‘painter-philosopher’ he spent a lifetime studying: stoicism. Blunt lived with the consequences of his actions, coping, he once said to a friend, with ‘this’ – waving his whisky tumbler – and ‘more work and more work’.

Anthony Blunt, art history, espionage, the culture, politics and literature of the 30s, 40s, 50s and 60s – this painstakingly researched book is a remarkable achievement.

Alun Severn

December 2021