Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Nov 2021

posted on 16 Nov 2021

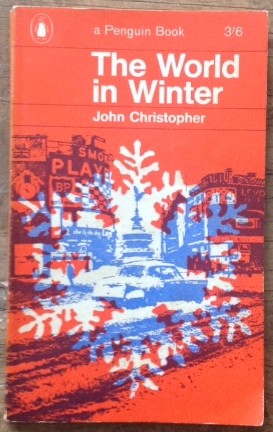

The World in Winter by John Christopher

John Christopher, the pen name of Sam Youd, is remembered (if at all) as the man who wrote the science fiction series Tripods aimed at teenagers, which then got adapted for a successful 1980s television series. However, this dystopian novel from 1962 for more adult audiences was largely neglected – following its 1964 release by Penguin books it then drifted out of print until it reappeared in 2016 in the Penguin Worlds series.

Set in Britain in the 1960s it tells of a natural ecological disaster that plunges the whole of the northern hemisphere into a civilisation-ending ice-age and cunningly reverses the colonial relationship between Europe and Africa. The book can be seen as a contribution to the general state of anxiety people were feeling in the early to mid-1960s over the seemingly endless series of potential world-ending threats Western society seemed to be facing. Writing in his engaging blog, Interesting Literature, Oliver Tearle puts it this way:

“British science fiction of the 1950s and 1960s seems to have been dominated by disaster novels: speculative fictions about the end of the world. This is hardly surprising, given the Cold War and growing threat of nuclear annihilation. In the decades that followed, the nuclear threat gave way to apocalyptic novels about a world ravaged and destroyed by climate change – a narrative obviously still very much with us, both in post-apocalyptic fiction and in the media.”

Perhaps unusually, Christopher’s book tries to blend complex ecological and political issues with an exploration of how social apocalypse also impacts on personal relationships and personal power. Sadly, not necessarily always successfully.

Having said that, it’s clear that the author knows how to write an exciting page-turner. Andrew Leedon, thirtyish, married to the attractive Carol and with two children, has a successful career in broadcasting. As first rumours of changes in the power and heat of the Sun emerge, he develops a friendship with a senior civil servant, David Cartwell and his wife Madeleine who know more about what might be a passing story of interest for his audience. But it soon becomes clear that the nasty winter that has set in is more than just a seasonal glitch and that something serious is afoot. And this insipient disaster is mirrored by the domestic disaster of Leedon’s wife leaving him and declaring her love for Cartwell.

As the big freeze develops, Cartwell uses his position to arrange first for Carol and her children to leave for a new life in the more temperate climate of Nigeria – and for Andrew and Madeleine to follow her a little later. The move to Lagos seems a sensible one until the Nigerian government decide that the flood of white westerners entering the country provides problems that need addressing and seizes all their money. The new immigrants are seen by the indigenous population as an underclass that can be exploited and marginalised – shunted into slums and servile jobs with the women forced into the role of ‘escorts’.

But Andrew and Madeleine – now virtually partners – are saved from their penury by complete accident when Andrew meets a Nigerian he had befriended back in London who now has influence and gets him a much sort-after job in broadcasting. As the ice-age progresses and establishes itself in the north, the politics of Nigeria start to emerge as the important theme and Andrew’s new mentor convinces him to join an expeditionary party that plans to establish a base (and ownership) of the newly ice-bound Britain. They set out on the mission with a fleet of hovercraft….

I’m not going to reveal any more of the plot at this point because you may want to read how it plays out for yourself.

This is a book with big themes – global, political and personal – and in some ways the scale of the ambition feels like it gets in the way of the drive of the book. Packing so much into a shortish novel inevitably means some of the themes get only cursory treatment and I was left wondering whether it would have been better to leave them alone rather than to treat them superficially. In the end I’m left unconvinced by the personal relationships and I felt much more could have been done with the inversion of the colonial relationship between Europe and Africa and the internecine conflicts within Nigerian society.

But all that said, it’s certainly a book worth picking up if you see a copy – the new paperback isn’t too expensive (although you’d pay considerably more for a hardback). It’s certainly a book that deserves to be in print and one which still has something to say to today’s readers.

Terry Potter

November 2021