Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 03 Nov 2021

posted on 03 Nov 2021

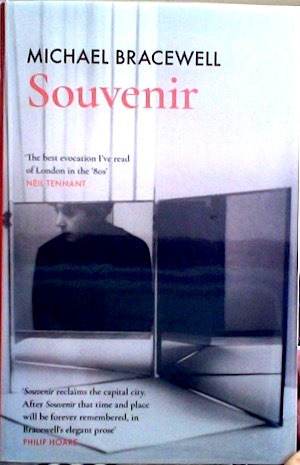

Souvenir by Michael Bracewell

That Michael Bracewell’s latest book, Souvenir, is a slender volume (120pp), part essay, part memoir, part tone poem, may ring alarm bells for some. That he is a novelist, essayist, cultural commentator and critic with a particular interest in music, subcultures and conceptual art may make those bells ring even more loudly. It sounds as if it is probably going to be just the kind of book that often disappears up its own fundament in a puff of pretention and abstraction.

And I would agree. In most instances you would be wise to listen to those alarm bells. But in the case of Souvenir, it isn’t so, because we have Bracewell’s wonderful prose.

Souvenir: London, 1979-86 – to give the book its full title – is a sort-of-memoir of London’s post-punk, pre-digital, pre-gentrification cultural scene. Bracewell’s prose has echoes of Martin Amis, Iain Sinclair, certainly a touch of William Burroughs, but also plenty that is wholly original. You can read it in a single sitting more or less, although I found it benefits from not being rushed.

It is about life in London from the late-70s to the mid-80s – the music of the time (post punk, new wave, elektronische musik, obscure art-music compilations that are now legendary, such as those on the Belgian label Les Disques du Crépuscule), the subcultures, the art provocations, the squats and dereliction, and the fashions and philosophical inclinations.

But more than any other single thing it is really about memory and atmosphere and what Bracewell does brilliantly is capture the fleeting impressions and ghosts of sooty, pre-internet, “electrical-mechanical London” – closer in many respects to the decaying grandeur of Europe’s pre-First World War imperial capitals – just as it was about to be swept aside by digitisation, the financial Big Bang, the Docklands Development Corporation, Thatcherism and rapacious property development. It is essentially a book about loss.

It is impossible to enter this world without resorting to quotation, for it is the prose that makes it. Here’s a taste.

In the late-70s punk had seemed to offer a vision of modernity itself imploding – “the white goods and deodorants and fluorescent lighting tubes and flyovers and subways and supermarkets becoming the ancient history of a science fiction present”, a new wasteland – emphatically not Eliot’s mandarin vision – “occupied by orphan adolescents, warming their hands by the flames of a burning television”.

But by the early-80s something new was happening:

“After the freezing winter of 1981, with its hard frosts and clear icy twilights of intense stillness, and quiet skinny boys hunched in old raincoats, always having to walk, listening to New Order, reading John Wyndham and JG Ballard, and pale art school girls in the thrall of Schiele, Erté and David Sylvian, there occurred in the pop-style zeitgeist a role-playing fantasy.”

There, the scene is set. Bracewell’s demi-monde is about to dip into its treasure chests of finery:

“…zoot suits, pinstripes and keychains, Alma Cogan, spivs, Julie London, Old Compton Street, Expresso Bongo and The Talk of the Town; a streetwise fast-talking cool proletarian notion of Jewish tailors, Bakelite, Beat Girl, pomade, strippers, Demob and Demop, coffee bars, beehives, impresarios, modern jazz, taffeta, nightclubs, Stephen Ward, rockabilly, stout, diamanté and upright bass…”

But alongside this fantasy of pre-swinging, pre-Beatles London, Bracewell says, was a counter-fantasy, “a cult of the abject, industrial, occult, transgressive, clever, days in a tower block east of Old Street, nights in Heaven or The Final Academy”. This shadow-side knelt at the altar of “Burroughs, Debord, Pasolini and Bataille”. This is what Bracewell excels at – disentangling and contrasting currents in fashion and their associated subcultures, sometimes capturing a moment or a trend with epigrammatic brilliance: for example, “…the mad thin male voice,” he says of vocalist John Lydon in his post Sex Pistols band, Public Image Ltd, “the voice of a self-loathing world-hating Victorian malcontent”.

I pull these vignettes out not quite at random but to give an impression of Bracewell’s preoccupations and technique. For this, in various forms, really is the sum of the book. There isn’t really a chronological narrative, there are memories, impressions, encounters; and there isn’t really a grand theory – no big idea for reclaiming what hyper-capitalism and global finance have stolen, and certainly no political strategy.

For Souvenir is first and foremost a book of cultural history and if its concerns are not yours, then frankly no amount of burnished prose is likely to win you over. It certainly isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. But if the London of this period does interest you and like Bracewell you mourn the subcultures of that period, then it is a feast.

One more vignette. Richard Rogers’ Lloyd’s of London building (“Armani meets Alien”, as Bracewell notes) has just opened. “Long summer evenings, 1986. Shepherd’s Market alley maze, when Mayfair was half empty; the abandoned mansions, in those days, and quiet side streets like dank Venetian canals…” In the distance, a lone man, barely glimpsed – “tall, suited, owlish…head down, hurrying”. He, the unnamed man, “had done no work of the kind that augments vortices, not for months; he would return home nightly from the bank, and fall into a leaden slumber until bedtime.” It is of course arch-modernist TS Eliot, a presiding presence in this terrific little book, rushing headlong towards another wasteland.

Alun Severn

Noveber 2021