Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 31 Oct 2021

posted on 31 Oct 2021

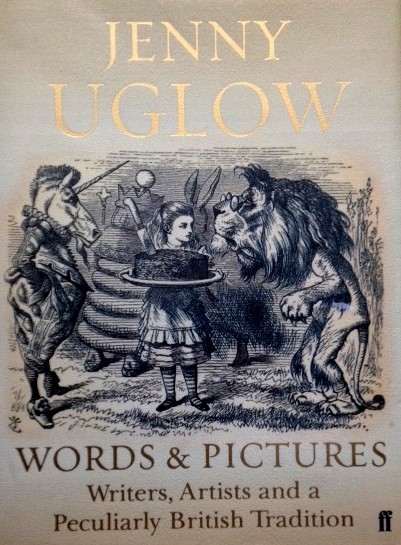

Words and Pictures by Jenny Uglow

Subtitled ‘Writers, Artists and a Peculiarly British Tradition’ and written by the usually reliable Jenny Uglow, the idea of a book exploring the relationship between writers and illustrators sounds like an absolute winner. We’ve become quite used to books that analyse the role of the illustrator when it comes to children’s books but in the world of adult literature we’re much less familiar with how author and illustrator can be a symbiotic partnership that results in more than the sum total of the individual parts.

This is quite a slim volume and so I was expecting that this would be one of two things – either a broad overview of some of the illustrating highlights from the world of adult literature or a more philosophical consideration of the relationship between words and images. In fact it’s neither of these – although to be fair its closer to the latter than the former.

Actually, despite the fact that the book seemed to get some very positive critical reviews on its release, I found it hugely disappointing and a bit of a dogs dinner to be frank. Uglow has taken the decision to look at three specific examples of illustration and text: Milton and Bunyon and the artists that illustrated their works; Hogarth and Fielding; Wordsworth and Bewick. Those familiar with Uglow’s work will also note that she has published much longer books exploring the life and works of both Hogarth and Bewick and it’s impossible to escape the feeling that she’s using up some of the leftovers from those studies.

We start well enough with a look at the artists that illustrated Pilgrim’s Progress and Paradise Lost and she makes a good case for the way illustration helped interpret these texts but she also builds an argument that the style of illustration tended to reflect the social status of those authors and their work.

But after that the links between author and illustrator become tenuous in the extreme and I was getting increasingly frustrated. Hogarth was not a direct interpreter of Fielding’s novels – although they certainly shared a similar world view and intellectual milieu. So what are we to learn from this that isn’t covered elsewhere in the literary and social histories of the 18th century?

That in itself is a disappointment but when we come to Wordsworth and Bewick there really is no link between the two at all in terms of direct illustration of text. Again it’s true that there’s a temperamental congruity between artist and writer – or at least there was for a while – but she seems to be stretching the point to say that the two creative minds can be yoked together in any sort of partnership.

The final section that she calls Coda pulls back some of the ground and starts to get into the territory I’d expected originally and there’s some interesting stuff on Victorian illustration and Dickens in particular. But for me, it’s too little too late and the overwhelming feeling is of a great idea that remains unrealised.

But I should stress that my disappointment seems to be a minority opinion compared with the contemporary reviews and, as always, you shouldn’t just take my word for it. If you want to find out for yourself, paperback editions are available for not much more than a fiver.

Terry Potter

November 2021