Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Oct 2021

posted on 05 Oct 2021

The Canterbury Tales – Modern or Middle?

I recently found a very fine two volume Folio Society 1961 edition of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales bound in brown leather and fawn cloth with woodcut illustrations in black and white from artist Edna Whyte. My edition also contains a series of colour postcards illustrating the various tales sprinkled throughout and I’m not at all sure whether a previous owner has introduced these or if they came as original with the first printing. It’s a lovely book. The text itself is the ‘modern English translation’ by Nevill Coghill and anyone from the past thirty or forty years who has had to study Chaucer at almost any level will recognise that name because Coghill’s is the version used for the Penguin Books Classics edition.

I studied English literature at university in the early 1970’s and I don’t think I’ve picked up a copy of Coghill’s version since that time. Reading The Prologue and The Knight’s Tale that follows it, was enough to remind me of my disgruntled, ruddy-faced university tutor staring in disbelief at the sight that confronted him: half a dozen callow and hairy seminar students that the poor fellow had inherited all with Penguin Classic copies of The Canterbury Tales on their laps – some better thumbed than others.

This was one of the very first tutorials we’d be scheduled to attend and we’d been set the task of reading Chaucer’s Prologue and at least one of the following tales so that we could spend a gainful hour pontificating and considering what we had gleaned from the exercise. For my part, I have to be honest and confess that I was hoping someone else had more to say than I did because my insights seemed less than piercing. But we never actually got to discuss any of Chaucer’s verse because, working hard to keep a lid on his mounting apoplexy, our much-put-upon tutor, purple of face, asked whether any of us had actually taken the time to study the reading list. It was quite clear, he said with growing self-control, that Canterbury Tales in modern English were not appropriate reading matter for university students. Chaucer, he said, wrote in Middle English, beautiful and poetic Middle English and that’s what we had to read. We were summarily dismissed from his room and sent on a mission to find a reputable version.

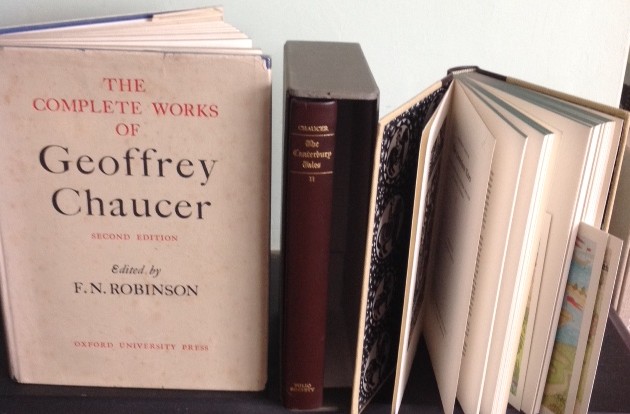

Upstairs on my bookshelves I still have my copy of The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, edited by F.N. Robinson I bought that day from the local bookshop and it still has the clumsy pencil annotations I made in preparation for the re-run seminar the following week. I don’t remember too much about the actual seminar but I will never forget the look of outraged hurt on my tutors face as he looked poisonously at the Penguin Coghill translations we all pulled out of our bags on that first day.

Ever since that experience I’ve always assumed that there is something fundamentally inferior about modern English interpretations of older texts – I bridle when people ‘update’ Shakespeare or mock the ‘complexity’ of any texts not written in colloquial modern English. But is this fair? Nevill Coghill was, after all, an established and respected Chaucer scholar and there are plenty of people who say kind things about his ‘translation’.

So, putting the two texts side-by-side, I thought I should try again and see if the Coghill version was one I could read and enjoy. But skilful as Coghill had been, reading it still felt clumsy and prosaic when compared with the wonderful rhythmic muscularity of Chaucer. Coghill had preserved the sense of the original but had somehow ironed-out the magic of the language. What follows is the opening Preface, first in translation from Coghill and followed by Chaucer’s original:

When in April the sweet showers fall

And pierce the drought of March to the root, and all

The veins are bathed in liquor of such power

As brings about the engendering of the flower,

When also Zephyrus with his sweet breath

Exhales an air in every grove and heath

Upon the tender shoots, and the young sun

His half-course in the sign of the Ram has run,

And the small fowl are making melody

That sleep away the night with open eye

(So nature pricks them and their heart engages)

Then people long to go on pilgrimages

And palmers long to seek the stranger strands

Of far-off saints, hallowed in sundry lands,

And specially, from every shire’s end

Of England, down to Canterbury they wend

To seek the holy blissful martyr,* quick

To give his help to them when they were sick.

Whan that Aprille with his shoures sote

The droghte of Marche hath perced to the rote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

5

Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halfe cours y-ronne,

And smale fowles maken melodye,

10

That slepen al the night with open yë,

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages):

Than longen folk to goon on pilgrimages

(And palmers for to seken straunge strondes)

To ferne halwes, couthe in sondry londes;

15

And specially, from every shires ende

Of Engelond, to Caunterbury they wende,

The holy blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen, whan that they were seke.

Chaucer’s verse takes a little getting used to, I will agree. You have to do a little bit of work to adjust your expectations but once you’ve hit the rhythm, the sense is not too hard to follow – no harder than Shakespeare in my opinion. By the way, it helps to read it out loud….

The argument that the modern English version will make it accessible and immediate seems like common sense but in fact it’s a process that demands a sacrifice – in this case the loss of the poetic essence of the text. And that’s a price I don’t think is worth paying. I’m reminded of the arguments that periodically emerge about the ‘translations’ of the Bible into various modern English versions and whether the poetry of the King James Bible is in some way central to expressing the religious mystery.

If works of literature in their original versions require a bit of work to master then maybe that adds to their value rather than detracts from it. I’m sticking with by old Robinson edition and keeping the Coghill translation as a curiosity….

Terry Potter

October 2021