Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 23 Sep 2021

posted on 23 Sep 2021

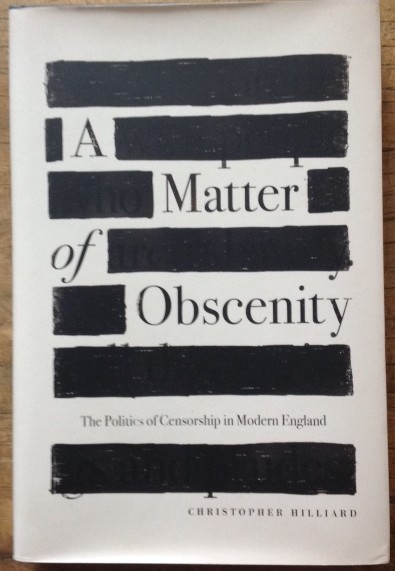

A Matter of Obscenity: The politics of censorship in modern Britain by Christopher Hilliard

Christopher Hilliard’s book is one of those rare things – an academically robust, research-rich, engagingly written page turner. And, if you’ve got any doubts about the academic credibility of the research, 70 or so pages of chapter notes at the end should satisfy you on that score.

At the heart of Hilliard's book is the assertion that censorship policy and practice is symbiotically linked to the development of political and social policy and it’s a thesis that the author systematically sets out in a chronological journey through the history of censorship in Britain from the Reform Act of the 19th century to the early 1980s. His focus is primarily on printed matter – books and pamphlets – but inevitably he also spends some time talking about censorship of the theatre, cinema and television and the inter-relationship of these cultural products.

The British approach to censorship has been heavily informed by John Stuart Mill’s notions of liberty and this has meant that the state has been less concerned with the prevention of the production of material than with its distribution. This is what makes the story of the Reform Act so important to the policy of censorship - the political fears of the ruling middle and upper class elites, that an extension of the franchise would see a much bigger (and in their eyes, uncouth) working class eclipse their interests and their right to rule, was mirrored, according to Hilliard, in what he called concerns over the ‘literary franchise’.

Put crudely, it is perfectly acceptable for educated, cultured middle classes to have access to morally challenging books like Boccaccio or Rabelais but it’s quite another to put these texts in the hands of the relatively uneducated childlike masses who do not know how to deal with them and don’t have the same solid moral base the discerning (richer) middle and upper classes have:

“Not every mind was equally susceptible to moral corruption. Whether a publication was marketed to those whose minds were open to immoral influences – whether it was likely to fall into their hands – had a bearing on whether it would be condemned under the Obscene Publications Act.”

And this notion of the wrong person getting hold of such material runs right through the history of British censorship and turns it into a indisputably political issue.

Hilliard also deals engagingly and directly with the thorny issue of what was to be considered obscene material and worthy of censorship. The law covering this was concerned not with offended morality but with material likely to breech the peace. Sir Philip Yorke, attorney general in the middle of the 18th century put it this way:

“What I insist upon is, that this is an offence at common law, as it tends to corrupt the morals of the King’s subjects, and is against the peace of the King. Peace includes good order and government, and that peace may be broken in instances without…actual force.”

Later, in 1857, the so-called Hicklin test used the construct that something could be considered obscene if it tended to ‘deprave and corrupt’ the person reading or viewing it. This, needless to say, did nothing to settle the notion of what obscenity was but simply opened more contested debate: just what did corruption and deprevity mean?

Hilliard takes us through some of the more famous cases of censorship – Joyce, Lawrence, Radclyffe Hall, American pulp fiction, the Oz Trial – and despite the fact that the details of many of these cases are well enough known from other publications, I think the author harnesses them well into his central story.

And that central story remains one where censorship seems to always be a question of not whether something should exist but who has the right to view it. That remains the central political issue and the battles to control that right-to-view or read run through history and, as Hilliard addresses at the end, incorporates debates around diverse ideologies like feminism and religious identity.

A fascinating subject has been brought to life here with skill and excellent research and don’t be put off by the fact that this will be seen as an ‘academic’ study – it’s readable and genuinely thought-provoking.

It’s available as a hardback from Princeton University Press and you can order it from your local independent bookshop.

Terry Potter

September 2021